|

|

|

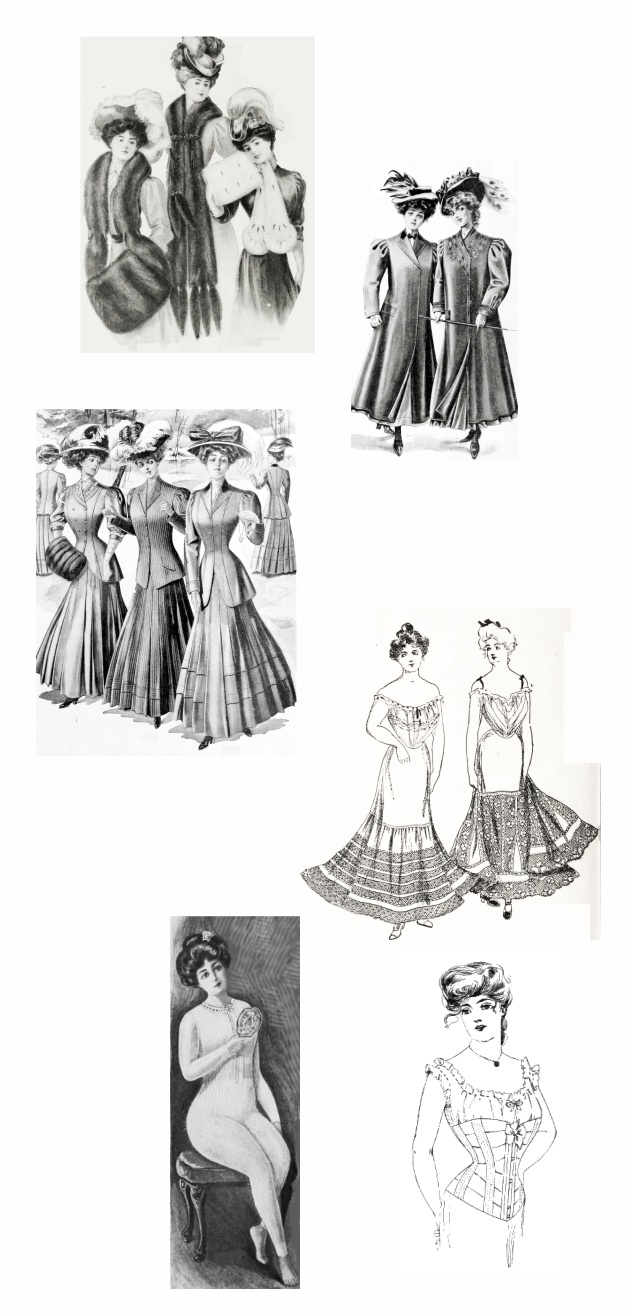

Below zero temperatures

December of 1903 was the ninth coldest December in Chicago's history.

When people dressed for that day's

outing to the city, it was four degrees below zero.

They had to travel by train and/or carriage to get

to downtown Chicago. Once there, many then had to

walk one to two blocks from the train station to the

theater. Since they were going downtown and to the

theater, fashion would have been a consideration,

but warmth probably took precedence.

Weight

In 1903 there were fur muffs and scarves atop outer

coats and/or suits, atop dresses, atop petticoats,

atop corsets and stockings, and for some, atop union

suits. One report estimates the average lady wore an

amazing thirty-seven pounds of clothing.

There is no way to know how many Iroquois matinee

attendees checked their outerwear but, based on

witness testimony and the

pile of garments collected after the fire, it is safe to say that

for many, escape was made more difficult by a

reduction in agility caused by ankle-length

garments, extra weight and

bulkiness. In their struggle to survive,

audience members left behind hats, coats,

muffs, even shoes.

Fashioned to death.

Protected from flames by bodies; crushed to

death by bodies.

Fashion killed women at the Iroquois. Corsets

constrained breathing in a situation in which

even small amounts of oxygen were a matter of

life and death. Long skirts were stepped

on, pulling women to their knees and then to the

floor where they were trampled, their bodies

becoming obstacles on which others tripped and

fell, creating piles of victims, all pleading

for help and desperately grasping anything they

could reach, which usually meant the skirts of

other women and girls. Some women at the bottom of such

piles were insulated from flames by other bodies but

were suffocated — not from smoke but when their lungs were

crushed from the weight of those same bodies.*

Hand-stitched seams probably saved lives at the Iroquois Theater

Post-fire photos taken inside the auditorium

show scraps of fabric littering railings and

seat backs, and reports from people who observed

survivors fleeing the theater often mentioned

torn clothing. Curiosity led me to a

failed attempt to tear contemporary garments.

Could I do so if my life depended on it?

No way, but could someone stronger do so?

A chance visit at an antiques auction gave me

the opportunity to examine the stitching on a

homemade dress from the early aughts. The

stitches were straight and uniform but longer

and looser than I expected. I could have

easily torn away the sleeves or the bodice from

the skirt. That led me to seek input from

a recognized authority and author on antique

clothing who confirmed that the seam strength of

hand stitched garments was weaker than seams on

machine stitched garments.

Ready-to-wear garments with machine-stitched seams were not

yet universal in 1903 and the days of a sewing

machine in every home was a couple years off.

The evidence of both situations is that the 1900

U.S. Census and 1903 Chicago city directories

were filled with listings for dress makers.

It was still a thriving cottage industry.

As it related to the Iroquois disaster, family

members searching for loved ones in Chicago

morgues oftentimes brought scraps of fabric from

the dress or shirt the victim had been wearing

when they went to the theater. Whether

they retrieved the scrap from a chest at home or

from the family's favorite dressmaker, they were

able to do so because the garments had been

homemade, and evidence of torn clothing at the

Iroquois says many had been hand stitched.

Had the seams not failed, more women would have

been drawn into body piles by the death grips of

those trapped at the bottom.

|

|

Discrepancies and addendum

*

According to a 1917 article by Chuck Remsberg, former editor of Force Science

News,

six-hundred-twenty-five pounds of compression on a

person's chest is fatal.

With the average weight of women in 1903

being around one-hundred-twenty-five pounds,

and an average chest thickness of fifteen

inches, victims at the bottom of the six-

and eight-foot high stacks of bodies found

at the Iroquois were weighed down by four to

seven bodies, amounting to five hundred to

800 pounds.

|