|

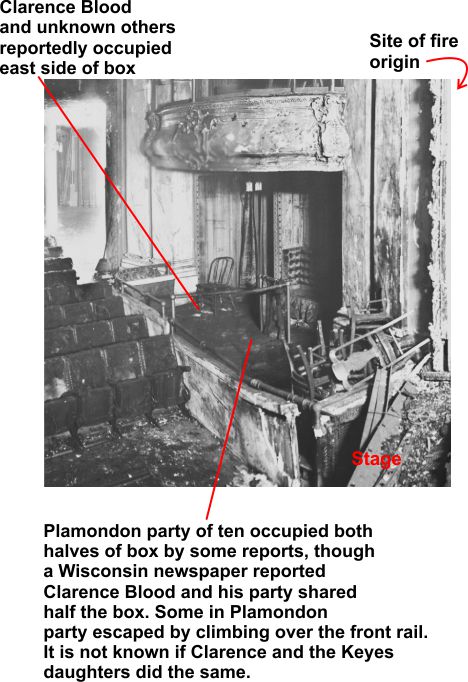

Twenty-six-year-old civil

engineer Clarence C. Blood (1877-1919) reportedly

shared a first-floor box seat on the south side of

the Iroquois Theater.* In a lengthy newspaper

interview, a young woman in the

Keyes theater party of ten gave a detailed description

of what she and her companions experienced in that

same box (see link below). According to her, her

party occupied both halves of the box. The newspaper

story about Clarence Blood's seating and activities

at the Iroquois, on the other hand, came from his

father in Appleton, Fred H. Blood, a week after the

fire. My best guess is that when proud father Fred

and the Appleton reporter were shy of details, they

speculated about what happened. In their

imaginations, Clarence was quite the hero.

The fire broke out within twenty feet of the

box seat. The Keyes party, comprised of young women

from wealthy Chicago families, remained seated for

much longer than I would have. By the time they

exited, they had to brush flaming shards from their

hair and clothing. Newspaper stories in Clarence

Blood's hometown told of their local hero grabbing

two "little" girls from the box, daughters of an

Evanston banker, one under each arm. With "Herculean

strength and as if prompted by providential

dictation..." "remained unswerved in his giant-like

efforts and after several minutes of nearly

superhuman fighting, managed to get to the

street." Reportedly Clarence then incurred a gash on

the back of his head from a falling beam, became

semi-conscious, was taken to a hospital and given

restoratives until he regained consciousness.

The story of Clarence's heroism is as

problematic as the location of his seat. The "little

girls" in the box were aged 16, 16, 19, 19, 20, 21,

21, 22, 25 and 48. The Keyes daughters, who best fit

the description of his distressed damsels, were aged

16 and 25.† According to age/weight tables for women

of that period, each would have weighed 90-152 lbs.

Clarence did not hoist a minimum of two hundred

pounds and maneuver a distance of sixty to seventy

feet through a frenzied crowd. Perhaps he instead

put his arms around the girls and steered them

toward the exit. That's believable but if his arms

were around them, how did he push others aside to

clear a path? With his head? Maybe. Since his was

the only story of a falling beam at the Iroquois,

I'm more than a little inclined to discount it but a

fabricated head gash seems unlikely, perhaps an

angry theater goer carrying an umbrella brought it

down on his head. That scenario works for me.

It is telling that nothing about Clarence

being at the Iroquois appeared in newspapers outside

Wisconsin. Chicago newspapers did not mention his

heroism, injury or presence at the fire. Their lists

of severely injured did not include Clarence.

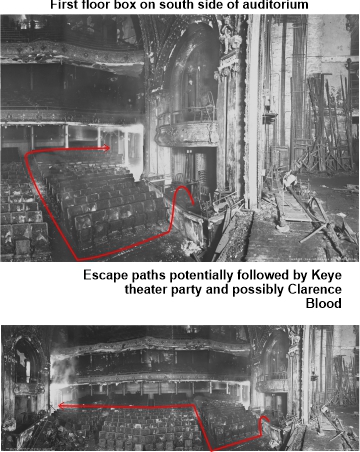

Escape paths

According to

a newspaper interview with one of the young women in

the party, Charlotte E. Plamondon, she and a

companion, Magdalen Elsie Elmore, ignored flaming

fabric to climb over the front brass rail (see

accompanying photo at right). They ran north between

the first row of seating and the orchestra pit,

turned east up an aisle, south toward the auditorium

exits (door

nos. 6-8), and made their way through the crush

into the main hall and eventually made it out the

front entrance. (See illustration below suggesting

the congestion that awaited in the main hall.)

They rejected the shorter escape route

through the curtained exit at the back of the box,

though it was the way they'd entered, thus the most

familiar route for them to have taken. It led to a

short flight of stairs and reached the same location

in the auditorium as their circuitous path. That

suggests the passage behind the box was filled with

smoke and/or flames.

Others in the Keyes party, including Clarence

Blood, may have taken the same path or may instead

have crossed the auditorium and exited through the

fire escape exits (door nos. 2-4) on the north side

of the structure, out onto Couch Place alley. The

button shoes, belt buckle, jewelry or teeth of a

victim jumping or falling from a second-floor

balcony or fire escape could have gashed his head.

That makes a Couch Place exit most likely. There

were many more falling bodies there than inside the

auditorium.

Clarence Curtice Blood Bio

Clarence had been married to Jeanette / Jane Adele Koch

(1879-1939) for over two years. In December 1903,

she was only three weeks away from giving birth to

their first and only child, Clarence Blood Jr.

(1904-1945). In December 1903, Jeanette remained at

their home in Iowa, her parents nearby, while

Clarence traveled to Chicago for an unknown reason,

presumably connected to his occupation.

During summers while in college and following

his graduation from the University of Wisconsin in

Madison, Clarence worked as a civil engineer on

railways, in 1898 going to work for the Chicago

and Northwestern Railroad (CNW) in Iowa,

reporting to

Hiram J. Slifer.‡

|

|

Clarence worked his way up in

railroad civil engineering from draftsman to

surveying supervisor. In 1900 he led a surveying

crew to investigate a Wisconsin railway line between

Merrill and Antigo.

Clarence retained strong ties to his boyhood home in

Appleton, Wisconsin

through his parents — hardware store retailer Fred

H. Blood and Lillian Curtice Blood — and three

siblings. Fred Blood was, in 1902, the earliest

Appleton, WI settler still living, having arrived

there as an infant with his parents in 1848 after

leaving his birthplace, Green Bay, WI. Before

entering the hardware and lumber industry, Fred

worked as a train conductor and coal dealer, serving

as engineer on some of the first trains in Appleton.

During his last decades, he kept the Appleton

newspaper well apprised of his activities and those

of his family.

through his parents — hardware store retailer Fred

H. Blood and Lillian Curtice Blood — and three

siblings. Fred Blood was, in 1902, the earliest

Appleton, WI settler still living, having arrived

there as an infant with his parents in 1848 after

leaving his birthplace, Green Bay, WI. Before

entering the hardware and lumber industry, Fred

worked as a train conductor and coal dealer, serving

as engineer on some of the first trains in Appleton.

During his last decades, he kept the Appleton

newspaper well apprised of his activities and those

of his family.

In the years after the fire

In 1905 Clarence and his family moved to St. Paul, Minnesota, where he worked in engineering for Northern Pacific Railway. By 1907 the family lived in Seattle, where they would remain, excepting a short while in Portland, Oregon with the Portland, Eugene & Eastern Railway (PE&E) in 1913. He occasionally went by a spelling variation of his middle name - Curtis C. Blood. (This may have been to avoid confusion with another man in the railroad industry named Clarence Blood. Clarence A. Blood, sometimes identified as Clarence H. Blood, was from Lehigh Pennsylvania, in 1911 accused of engaging in questionable trade practices.) Later in 1913, Clarence left civil engineering and became roadmaster for the Northern Pacific yard in Puget Sound, Seattle, Washington. (A roadmaster is part of a

railroads "maintenance of way" system, maintaining track in a given

division.)

|

|

Discrepancies and addendum

* Augustus Eddy and Carroll L. Shaffer, the brother

and friend of two members of the Keyes party,

Josephine and Elizabeth Eddy, occupied row seats a

few feet from the box. Shaffer was the son of

prominent newspaper and railroad man, John

C. Shaffer.

Though a few years older than Shaffer, from a less

moneyed family and a graduate of a Midwestern

university rather than Yale, Clarence Blood did work

for a railroad. My newspaper searches looking for a

connection between Clarence and Shaffer or Eddy were

unproductive. However, Clarence almost certainly

attended the theater with companions and I've failed

to learn who they might have been. Augustus Eddy

tried to reach his sisters in the box but was swept

forward by the surging crowd. Perhaps the Keyes

theater party originally numbered thirteen. The ten

women filled the loge so the males — Eddy, Shaffer

and, perhaps, Clarence — took nearby row seats. Eddy

and Shaffer were swept toward the exits while

Clarence battled his way to the box.

† Charlotte Plamondon's father, Charles Plamondon,

was an officer in a bank but the family did not live

in Evanston, nor did Elsie Elmore, the girl who

escaped the theater with Charlotte. Charlotte

described having jumped into the arms of a man when

she climbed over the box rail. She later guessed he

might have been an employee of the theater, stating

that he set her down in a row seat and told her to

remain there for a moment. Had that man been

Clarence, presumably she would not have described

him as a theater employee. (Will

J. Davis Jr. is a possibility. He was at

the theater when the fire broke out but newspapers

published nothing of his actions that afternoon.)

‡ Slifer attended Clarence Blood's wedding in 1901.

The same year that Clarence Blood died, 1919, Slifer

would also lose his life. The sixty-two-year-old

lieutenant colonel in the Corps of Engineers in

France during World War I, overseeing rail

construction for the 1st Army during the St. Mihiel

and Argonne-Meuse offensives, received a posthumous

Army Distinguished Service Medal. I found no

evidence that Clarence joined his mentor in World

War I.

|