|

Thirty-one-year-old machinist, Albert Alfson (b.1872)

brought his eighteen-year-old girlfriend to spend part

of the 1903 holiday with his parents and siblings in

Chicago. He and Margaret / Marguerite Love (b.1885) lived in McHenry County,

Woodstock, IL, about fifty miles northwest of Chicago,

where Albert worked at the Oliver Typewriter factory*

and Margaret as a clerk at a clothing and dry goods store. Albert

and Margaret were planning to marry but had shared

their secret with only a few friends.

The Love family

Nineteen-year-old Margaret May Love (spelled

Marguerite in some reports), nicknamed Maggie,

worked as a clerk for Jurene M. Thomas in Woodstock. She was the

daughter of Scottish immigrant Watson D. Craighead / Greighead Ronning Love (1853–1930) and Watson's

second husband, Irish immigrant William A. Love

(1832–1892), a veteran of the American Civil War.

Maggie was nine years old when her father died,

making her eligible to receive his veteran's

pension.

Watson married William B. Henrie, a fresco painter, and the couple

lived in Delavan, Wisconsin, later returning to Woodstock, IL.

Maggie lived with them in Delavan at least three years before

her death. Through her mother's three marriages Maggie had five

half brothers and sisters.

The Alfson family

Albert was one of eight children born to carpenter

Alexander (1836–1909) and Fredericka Caroline

Johnson Alfson (1840–1927), natives of Norway and

Sweden, of which seven survived prior to Albert's

death at the Iroquois. Albert's living siblings in

1903 were:

| Clara Alfson Hammersmark (John) |

Ida Marie Alfson Phipps (Frank S.) |

| Ella L. Alfson Foster (Charles) |

Hannah Alfson (d.1953) |

| Agnes Alfson Bingham (Theodore) |

John Alfson (d. 1927) |

In 1896-7, before moving to Woodstock, Albert manufactured bicycles and was a

member of a cycling club. By 1898 he described

himself in the city directory as a machinist.

In the accompanying photo from 1901, a group of cyclists

gathered for a race. Albert was most

probably not at this race because he had already

moved to Woodstock by 1901. It is interesting that cycling clubs

were hot at the dawn of the automobile in the same way

that cassette boom boxes were hot at the dawn of the

internet.

Probably standing at the back of the third-floor balcony

A story about the couple in

the Woodstock newspaper was lengthy: one-third of

the front page and another fourteen column

inches on page four. According to the story, the couple

purchased tickets in the front row but their floor was

not reported and Albert's family knew nothing of

what happened to the couple inside the theater.

I conjecture that if Albert had purchased tickets before

December 30, he would have known the floor and

mentioned it to his parents when he told them of his

front-row seats, that had his parents known the floor they

would have shared the information with the newspaper

reporter and, given the length of the story,

if the floor had been known, the information would

have been included in the newspaper story. If

Albert waited to purchase tickets

immediately before the opening curtain, as I

suspect, he may have spoken of his plan to purchase

front-row seats to one of the dozen Woodstock

citizens at the matinee (see list in panel below),

as they entered the theater or while

standing

in the foyer at the theater waiting to

purchase tickets. When he got to the

ticket counter, however, he may have learned, as did

other Iroquois attendees who lived to tell of their

experience, that front row seats were

sold out. For Albert and Margaret, returning on

another day was not a good option. The theater

was closed over the holiday, Albert's devotion to

his Methodist faith would have made attending the

theater on Sunday verboten and they had to be back to work in Woodstock

by Monday. If my many speculations are

correct, the reason other

Woodstock residents did not see Albert and Margaret inside the auditorium

is because they were only able to get standing-room

tickets at the back, and probably in the third-floor

balcony.

The marked difference in the

condition of Albert's and Margaret's bodies

indicates they became separated, with Margaret escaping from the auditorium and Albert

trapped inside and killed by the fireball.

Margaret may have been one of around twenty-five

people, including the

Strong family,

who ran toward the utility stairwell. Once the

wood door there (door

#40) was broken open with fireman Roche's ax, two or three in that

group were found to be alive, if barely. They

were first carried from the stairwell into the

manager's office at the front of the structure

(through door #34). To reach Dyche's

Drugstore, Margaret's bearers would have carried her

past Thompson's diner, which would become the

busiest triage center.

Families search for bodies

First responders took Albert's badly burned body to Rolston's mortuary.

After a two-day search his father, Alexander Alfson,

matched the fabric of a vest to other clothing on

his son's body.

|

|

Margaret's body, though free

of burns or evidence of trampling, was more

difficult to locate. Three from Woodstock took

on the gruesome task: her half-brother, Charles

Arthur Ronning (1879–1917),† Arthur Erickson

(1884–1957), a co-worker of Albert's at Oliver Typewriter, and Jurene

M. Thomas, Margaret's employer. For a short while

the group thought a badly burned body at Rolston's was

Margaret but decided not. Erickson kept searching

and found her unmarked and unburned body at Boydston

Bros. Funeral Home, over five miles south of the

Iroquois Theater at

4227 Cottage Grove Ave. Sounds to me

like funeral business was being spread far and wide.

Reportedly, Margaret was one

of several Iroquois Theater victims carried to a

drugstore where four physicians struggled for two

hours to save her life. The largest number of

victims were triaged through Thompson's diner with a

smaller number taken to Dyche's Drugstore at Randolph

and State.§

I was at first skeptical that

the drugstore scene was connected to Margaret and

the story shared with her family. Upon further reflection,

however, I think it could have happened as described. A triage site

less busy than Thompson's would

have allowed physicians more time to spend trying to

resuscitate the girl and to communicate their

frustration to the wagon driver who carried Margaret's

body to the Boydston's

Funeral home. There too, fewer bodies and a

less frenzied pace would have facilitated more

communication. Unlike Rolston's, Jordan's

and Sheldon's funeral homes, which took in 187, 135 and 47

Iroquois victim bodies, distant Boydston's took in only five.

The mortician and his workers probably knew more

about each of their five victims than was the case

at busier morgues. Boydston was not

alone in receiving only a token bit of the Iroquois

fire business. Furth Undertaking at 192 W.

35th, also five miles away, and Postlewaite

Undertaking at 322 Ogden (today's 1867 Ogden), three

miles away, each received fewer than six.

Boydston may have had particular reason to take note

of the unblemished condition of Margaret's body -

see below.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

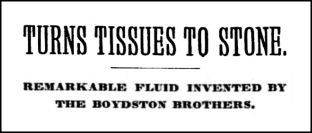

Just when I start thinking 1903 wasn't much

different than our times, something like this comes

along to remind me that it was over a century ago.

Check out this

newspaper story about 1896 experiments

to invent an embalming fluid that would preserve

corpses by turning them to stone.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Funerals

Albert's funeral was held

Sunday, Jan 3, 1904, at 1 pm in Chicago, conducted

by Rev. Newton A. Sunderlin

(1849-1935) of the

First

United Methodist Church in Woodstock. Two

other pastors participated. reverends Loomis

and Hanson were from the family's church in Chicago,

the Second Swedish Methodist Episcopal Church. Two hundred guests attended,

over half of them from Woodstock, IL,

including his

Sunday School class. Albert was

described as religiously devout and newspaper

references to his activities seem to bear that out.

He was buried at Mount Olive Cemetery in Chicago.

Sunday School class. Albert was

described as religiously devout and newspaper

references to his activities seem to bear that out.

He was buried at Mount Olive Cemetery in Chicago.

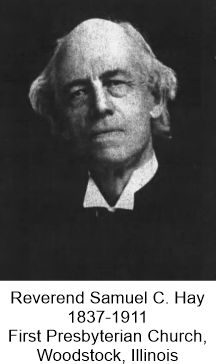

Margaret's funeral service was conducted by Rev. Samuel C.

Hay| at the First Presbyterian Church in Woodstock. The church

choir sang "Saved by Grace," said to be a favorite

that Margaret and Albert liked to sing as a duet.

In the years after the fire

In January 1909 Albert's

family received a $750 (inflation-adjusted to

$21,000) settlement from Fuller

Construction, one of only thirty-five awarded.

Margaret's family did not receive a settlement,

perhaps because her mother did not pursue it.

Watson and William Henrie remained in Woodstock,

possibly making it difficult to oversee a lawsuit in

Chicago. Albert's father, Alexander, passed

away in November that same year. Margaret's

employer, Jurene M. Thomas, closed her store in

Woodstock, relocated and remarried. Arthur

Erickson, who had persisted in the search for

Margaret's body, married Mary Pierson in 1907.

They had one child and settled in Belvidere, IL.

Margaret's half brother, Charles Ronning, remained

in McHenry County and raised four children.

|