|

In

Klaw & Erlanger's traveling Mr. Bluebeard

company, twenty-three-year-old William Plunkett

(1881-1942) (possibly having John as his actual

first name) was assistant to stage manager

William Carlton.

One of Plunkett's

tasks at the Iroquois Theater — when

Carlton remembered to assign it — was to close the

strip lamps on either side of the stage to allow

lowering the ornamented fire curtain.*

On December 30, 1903, during the second act, a fire

broke out on stage. In the pandemonium that

followed, Plunkett neglected to close the strip lamp

on the north side of the stage. According to

one witness, lamp operator H. Hill, Plunkett did,

however, remember to hit the switch†

to turn on a light bulb, possibly flashing, up in

the loft. It was the signal to riggers to

lower the fire curtain. Reportedly his supervisor, Carlton, was

not on the stage when the fire broke out, but in the auditorium

or lobby. House boss

James Cummings

was also away from the stage, at the hardware store.

And a substitute was manning the fire curtain ropes.

And the theater manager was at a funeral. So

contributing to the perfect storm was that several

key people were unavailable.

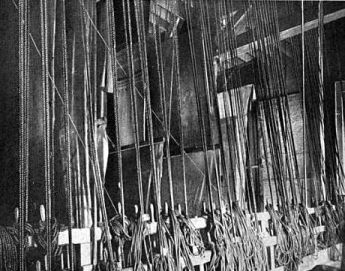

Not the Iroquois, just a loft shot to indicate John Dougherty's challenge.

The fellow manning the fire

curtain,

John Dougherty, was substituting for Fred "Slim"

Seymour, supervisor of all the flymen.

That made Dougherty and his assistant,

John Schmidt,

responsible for hundreds of curtains and drops.‡

Later remarks from Seymour indicated that though

a substitute, Dougherty was very capable and

experienced in the task.

Seconds passed as Dougherty and Schmidt spotted the fire curtain light bulb and remembered which rope

controlled the fire curtain, but the delay probably had little

impact on what followed: The curtain started

to drop and stopped, blocked by the strip lamp. While a handful of stage

workers, including Dougherty, tried to free the

curtain from the top of the lamp so the lamp could

be closed to let the curtain continue its descent on

that side of of the stage, hundreds of performers

and stage workers, chased by

flames, opened and fled through large double doors at the back of the

stage leading into the alley behind the

theater.

At the same time, vents in

the back wall of the theater were drawing air from the

auditorium and audience members opened fire escape

doors from the second and third-floor balconies.

The opened stage door produced a back draft and

the opened fire escape doors gave that back

draft

an extra push.

|

|

The gap beneath the fire

curtain became an opening to a wind tunnel through which the blast

of air from the opened stage door hurled a ball of

flame out into the auditorium and up into the

balconies. Those who had not yet escaped from

the auditorium died

on the spot, at 3:50 pm.

Persuasive instigator

Police arrested Plunkett the

night after the fire, December 31, 1903, along

with eleven other stage workers, in part to prevent

them from fleeing Chicago. According to reluctant

confessions from five of the men, Plunkett had persuaded them they

should disappear before the inquest began so they

packed their bags. Police got wind of the

scheme and moved in to make arrests, fearful that

the information sources were scattering like

cockroaches. Interestingly, one of the men who listened to

nineteen-year-old Plunkett's advice was his boss,

William Carlton.

Initially, police detained

stage workers to prevent them from going back to New

York. When questioning revealed contradictory answers,

police arrested and

charged the men with manslaughter due to criminal

negligence.

Judge Caverly rejected cash bail from Mr.

Bluebeard business manager, Edwin Price, and required

a $5,000 bond backed by real estate for each man.

Attorney

Thomas S. Hogan represented Plunkett at his

arraignment.

Plunkett bio

Plunkett was the slender and six-foot-tall, fair-haired

and blue-eyed son of European immigrants, Agnes Graffin Plunkett Cheshire

and the late Richard Plunkett, a carpenter. William quit school after

the 7th grade during the turbulent time of his father's death and mother's

remarriage. At age nineteen in 1900 he described himself as an

actor.

He had a couple female actresses living two doors down so perhaps they gave him

a leg up. As likely is that they looked at him as an important

connection. By twenty-three he'd been working for over a decade and had

skills sufficient to gain a position of responsibility in a major theater

road company — and to persuade five older men to flee from authorities.

In the years after the

fire

In 1910 he lived with his mother, stepfather and

older brother, Richard Plunkett, in Manhattan and described himself as a theater manager.

How much longer he remained in the industry is not known. A

William Plunkett was stage manager for a musical comedy that appeared at

the Royale Theater in New York City, Woof Woof in late 1929, but I failed to learn

if it was the same fellow who was at the Iroquois in 1903. Other than

Woof Woof, I found nothing tying a William Plunkett to the theater

after 1910. According to newspaper reviews, the show was a dog and

lasted only two months. Given that it opened weeks after the stock market crash

that kicked off the Great Depression, however, even a more promising production might have

failed.

|

|

Discrepancies and addendum

* It would be

revealed during the investigation that stage workers employed by the theater

were critical of Carlton's haphazard direction

regarding the

strip lamps. Some of their criticism was

related to the animosity between the theater

staff and road company staff. I don't have

to have worked in the theater industry to know

that our-team vs. your-team conflicts are

inevitable in such situations but suspect it may

have been aggravated when Klaw & Erlanger

productions came to a theater. Abraham

Erlanger was notoriously bad tempered and from

his subordinates viewpoint, probably difficult

to please. To his temperament add that he

was in charge of daily operations for a very

powerful producer, the Syndicate. He

wouldn't have been the first asshat to be more

attracted to asshattery than competency when it

came to filling authority positions in K&E's

traveling companies. Maslow and his hammer

come to mind. Asshattery wasn't Erlanger's only

tool but seems to have been the one he picked up

first.

† One of the two

Iroquois anniversary books, Chicago Death Trap,

states that Plunkett sounded a bell but

court testimony from operator of lamp #1, H. Hill,

who was standing nearby, expressed his criticism of

the fire-curtain alert, specifically because it was

only visual and not also auditory, thus dependent

upon a busy curtain operator seeing it flash.

It may also have been small in size, but that's

just a guess.

‡ Seymour had become ill

and was taken home by another stage hand, Wilson D.

Kerr, prior to the outbreak of the fire.

|