|

Day 1 — December 31, 1903

One of his first meetings was with a committee of

Chicago aldermen who had just completed a tour of

the Iroquois Theater, followed by a visit to the

city building department where they had spoken with

deputy building inspector

Louis Stanhope. The

Aldermen were

Ernst Herrmann,

Winfield Dunn,

John Jones,

Henry Eidmann,

Luther Friestedt,

Peter Wendling and

John Minwegen. Their remarks to reporters

while at the Iroquois were probably intended to

express their constituents' feelings, but reports of their

response reminded me of a flock of

angry geese.

Not intimidated by their honking and flapping, Harrison

informed the delegation

that the city

council was as much to blame as anyone else in

the Iroquois disaster, pointing out, "Gentlemen,

on Nov. 2 of this year I transmitted to the city

council a report on the condition of the theaters of

Chicago, calling the attention of the council to the

failure of all the theaters to comply fully with the

terms of the ordinances. The report was prepared by

the commissioner of building. [George Williams]. The

council sent the communication to the committee on

judiciary for consideration, and pending a report

from that committee directed the commissioner of

buildings to suspend enforcement of the ordinances."

Harrison added that according to his recollection,

the judiciary committee then sent the report to a

subcommittee that went to sleep.

Alderman Herrmann defended the ordinance suspension

as having been a delay to give them time to modify the ordinance

regarding proscenium arches, a modification that had

been suggested by the mayor, and went on to assert

that shows such as Mr. Bluebeard should be

outlawed. "They are immoral shows, and the

inflammable machinery needed to carry them through

is a menace to the lives of those who are induced to

go and see them." [!!!]

To the suggestion that the theaters should all be

closed until compliant with the ordinance, Harrison

replied: "It would be just as sensible to stop

running railway trains because there is an accident

on a railway as to stop theaters because of an

accident of this sort, no matter how deplorable it

may be."

Harrison instead sent two firemen to every Chicago

theater — then changed his mind about closing

Chicago's theaters. Over the next two days, he

would close thirty-five playhouses.

The aldermen

left the mayor's office, grumbling about ways to pay

him back for his harsh position - just as soon as

they contacted the judiciary committee and revoked the ordinance

suspension.

Day 2 — January 1, 1904

Harrison toured the Iroquois with building commissioner Williams,

alderman William Mavor, Iroquois designer,

Ben Marshall, a Chicago Tribune newspaper

reporter, architects Charles R. Adams, Emery Stanford Hall,

George Beaumont, Isaac Stern, George L. Pfeifer and

contractors Addison E. Wells and Victor Faulkenau.

Harrison and Marshall discussed Iroquois gallery

exits to the front of the theater.

Dance halls

In addition to the theaters, three hundred dance halls were closed.

|

|

Harrison recommended that the city council form a

committee to investigate the disaster. He

instructed the building department to instantly

prohibit performances at theaters that did not have

asbestos fire curtains and

prohibited "standing room" ticket sales throughout

the city. He instructed the city Electrician,

Edward B. Ellicott, to order every theater in the

city to immediately discontinue use of arc lamps.

Harrison invited the city's architectural societies

to appoint a representative to sit on a committee to

study the Iroquois disaster, including the Illinois

chapter of the American Institute of Architects, the

Architects Business association, the Builders Club

and the Traders and Builders exchange. This

assemblage was effectively created by the

Chicago Tribune's investigation.

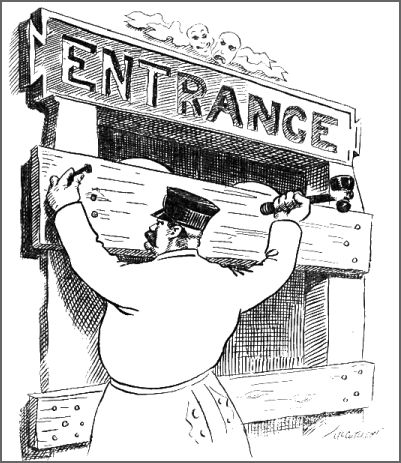

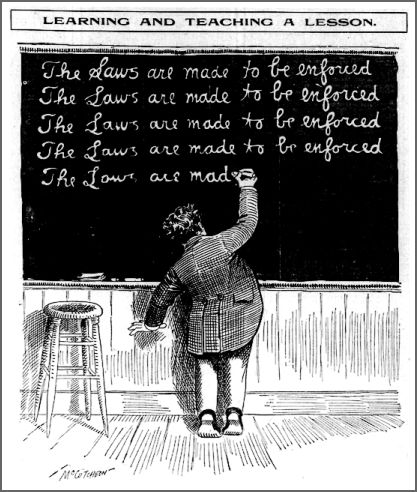

Closing Chicago's theaters

In ordering building commissioner Williams to

close Chicago's theaters, and directing that

they remain shuttered until they complied with the

city ordinance, mayor Harrison shifted some of the

responsibility for future actions from

his office to the theater owners and city council.

The closings made most everyone furious but he had

few choices. Amending the city's existing

ordinance, or drafting a new ordinance, was a job

for the city council, not the mayor's office, and

meeting those requirements was the job of the

theaters. The mayor's job was to enforce

whatever ordinances were in place. He hadn't

done so back on Nov 2, 1903 when he received

Williams report about the unsafe condition of

Chicago's theaters. Harrison had instead given

the council time to act and theaters time to comply.

It did not do so. The council responded with lollygagging, theater

owners did nothing, and nearly six hundred people died.

Closing the theaters was Harrison's way of saying,

"Game's over, boys. Time for all of us to

put on our big boy pants. Or, in his exact words,

"I am tired of packing responsibility for this

city. I will not do it any longer. The city

ordinances shall be enforced. I will give the city

council a chance to amend and revise them. If

the aldermen do not change the laws they will be

enforced as they are. I will close every building

which does not conform. That means churches,

factories, office buildings and stores."

Harrison went on to elaborate with

specific examples of a few of Chicago's contradictory

response to code enforcement.

|

|

Discrepancies and addendum

* It took several years of researching the Iroquois

theater disaster for me to reach the conclusion

Chicago's mayor recognized early on. The

Iroquois Theater disaster was a perfect storm that

could possibly have been prevented, starting with

more robust enforcement and accountability.

Mayor

Harrison's secretary, Ernest McGaffey

(1861-1941), was a poet, newspaper

journalist, attorney (partnered with alderman John

Smulski) and painter of miniatures, a democrat and a

failed candidate for alderman in the 28th ward. He was also a Ohio

native, son of John and Louisa Pratt McGaffey and

married to Mississippian, Cecile Rafalski. Their

first child was born two months before the

Iroquois Theater fire, for which he was

congratulated by president Theodore Roosevelt.

He had once worked as Roosevelt's personal press

agent and they corresponded while McGaffey worked as

Harrison's secretary. By 1920 the family had

relocated to California where he worked as a writer in

the publicity department of the Auto Club of

southern California. In 1941, the year of his

death, McGaffey wrote an article advocating

construction of a coast-to-coast road, 100-ft wide

as an important security need for America.

Iroquois Theater fire, for which he was

congratulated by president Theodore Roosevelt.

He had once worked as Roosevelt's personal press

agent and they corresponded while McGaffey worked as

Harrison's secretary. By 1920 the family had

relocated to California where he worked as a writer in

the publicity department of the Auto Club of

southern California. In 1941, the year of his

death, McGaffey wrote an article advocating

construction of a coast-to-coast road, 100-ft wide

as an important security need for America.

McGaffey first appeared in the Harrison

administration as assistant secretary to the new

board of local improvements in May, 1901, a position

paying $4,000 annually ($112k today), giving the

anti-Harrison Inter Ocean newspaper an

opportunity to criticize the mayor for appointing

inexperienced men to the board. Harrison had a

Twain-like response: "I have found that it is

better to put in honest men who have to learn the

duties of their office after their appointment than

to appoint experts who will have to learn honesty."

McGaffey was appointed to the job as Harrison's

private secretary in June, 1903. It was

rumored that he got the secretarial job because his

place on the board was given to another fellow as a

reward for dissuading celebrated attorney

Clarence Darrow from running for mayor and to switch

his support from Labor's mayoral candidate, Daniel

Cruice, to Harrison. McGaffey left his city

office along with Harrison in 1905.

|