|

Dr. Charles H. Albrecht (1864–1944)

Charles identified the dental remains of

Clara Reid. He was a resident of Waukegan, IL, about fifty miles

north of Chicago where he practiced

dentistry for over fifty years. Charles had

graduated from Northwestern's dental college

in Chicago. He later adopted

Anglicized spelling of

his name: Albright. Married to Mary E.

Cone Albrecht. They did not have children.

Dr. Harry Jay Combs (1871–1950)

Harry identified the body of

Elizabeth Duvall. He was married to Lillian M. Field

Combs, an artist in the print department of the Art

Institute at one time, and they had one

child, a daughter named Lorraine.

In 1943 they remodeled their century-old

home to vault the ceiling over the living

room. A relative has done much work on

the family's genealogy; the family photos

depict a happy family. Lillian loved

dogs :) Harry was the son of Amos and Virginia

Combs.

Dr. Fredrick G. Elwell (1854–1937)

Fred identified the body of

Anna Dixon.. He was married to

Louise Winter Elwell, an unusual woman of

her time in that she worked after marriage,

teaching public school in Chicago for fifty

years, serving as assistant principal at the

Gladstone School for thirty-five of those

years. They did not have children.

Dr. Victor H. Fuqua (1870–1930)

Victor made the identification that helped

unsnarl a body mix-up between two young

boys:

Howard Palmer and

Jimmy Henning.

Two weeks after the fire, Fuqua positively identified

the body of Jimmy Henning by

his teeth. The body was being held in

a vault awaiting shipping. The family of Howard Palmer

returned Jimmy's body to his family and

hired a detective to find Howard's body —

that when found was also identified by a

dentist but his name was not reported. Fuqua

was said to be a lifelong friend of Jimmie's

father, James Henning. Victor was

married to Grace D. Williams Fuqua and had

one child, a daughter named Hortense.

Dr. William A. Hoover (1861-1937)

William identified the body of Anna Hanson,

a school teacher from Gibson, Illinois who

had roomed and the Hoover household.

|

|

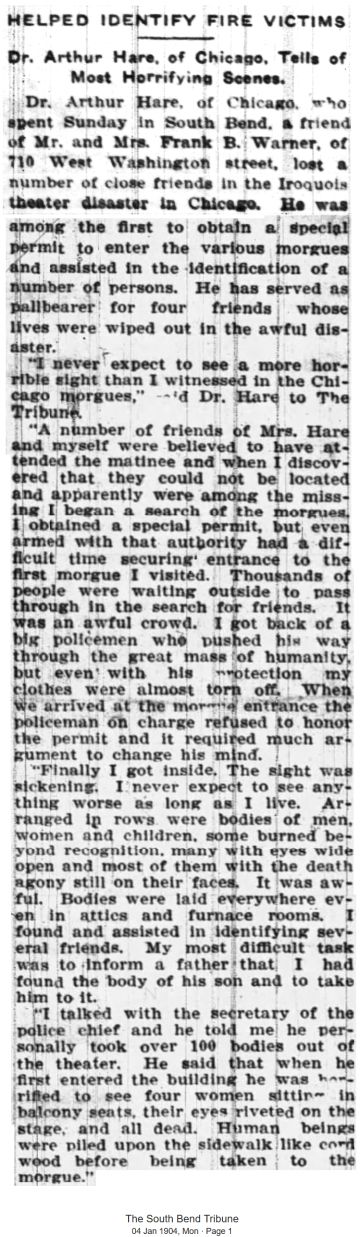

Dr. David Arthur Hare (1873–1959)

David Hare sometimes went by his middle

name, or his initials.

His daughters were young when he

passed away. As they grew older, his

wife shared stories of their father's life.

One of the stories was about David having

helped identify Iroquois Theater fire victims.

Fortunately, one of his daughters shared

that nugget. I did not find his name

in 1903/4 Chicago newspapers, but the

South Bend Tribune ran the story at

right on Monday, five days after the fire.▼2

David Hare sometimes went by his middle

name, or his initials.

His daughters were young when he

passed away. As they grew older, his

wife shared stories of their father's life.

One of the stories was about David having

helped identify Iroquois Theater fire victims.

Fortunately, one of his daughters shared

that nugget. I did not find his name

in 1903/4 Chicago newspapers, but the

South Bend Tribune ran the story at

right on Monday, five days after the fire.▼2

The Trib story doesn't reference dental identification

but contains two useful bits of unrelated information.

The first is that some of the morgues were so

overly full of bodies▼3 that they

had to lay them out in attics and furnace

rooms.

This is useful in better

understanding why the morgues needed to close the

morgues at midnight the night of the fire to

organize bodies. (Which is why Hare

had such a difficult time gaining entrance.) Routing streams of

morgue visitors up and down stairwells was a

serious logistics problem.

Hare's remarks

also support the inaccuracy of

out-of-Chicago newspapers who exaggerated

the number of victims found dead in their

seats to suggest that there were hundreds —

a titillating blame-the-victim scene worthy of a contemporary

horror film.

Hare's quote from Police Dept Secretary,

Simon Si Mayer, corroborates the observations

of fireman

Michael Roche that only a

handful of people met their fate while

sitting calmly in their seats at the

Iroquois.

|