|

After less than a

year in "The Wild Rose" I opened on January 21, 1903, what was

destined to be the most memorable engagement in my history. Klaw &

Erlanger had recently taken up the producing of great extravaganzas,

importing the big Drury Lane pantomimes from London and giving them

an American farcical touch and a bit of additional lavishness. In

splendor of staging and costumes they fairly out-hendersoned

Henderson.

Their first production of this kind. The Sleeping Beauty and the Beast, had just

run its course, and now they staged "Mr. Bluebeard."

In this memorable production, the Sister Anne of the original legend, who had been

ruthlessly eliminated from Henderson's version, now appeared as the

leading comedy character, and I was assigned to play it. Dan McAvoy

at first essayed "Bluebeard," but was soon replaced by Harry

Gilfoil. Flora Parker was Fatima; Adele Rafter was Selim; Norma Kopp

was Abdallah; Bonnie Maginn, a Chicago girl, was Imer Dasher;

William Danforth was Mustapha and Herbert Cawthorne was Irish Pasha.

I was supplied with two excellent songs Billy Jerome, "I'm a Poor,

Unhappy Maid" and "Hamlet was a Melancholy Dane"; and I had a scene

with a comic elephant which seemed to please the patrons greatly.

Newspapers exhausted their stock of adjectives in trying to describe this

colossal affair. "Stupendous!" "Magnificent!" "The limit of

pictorial stage art has been

reached." "Extravagance can go no further." "One of the most

gorgeous spectacles ever seen in a theatre." Such were a few of the

comments. There was a flying ballet which floated in the air like

thistledown. At one point the leader soared from the stage out over

the heads of the audience almost to the gallery rail, scattering

flowers as she went. That trolley wire upon which she was carried

was destined to play a tragic part in the history of the show before

the year was out.

At another moment

in the play a girl on the stage stepped towards the footlights and

held out her hands ; one of the fairies floated down as gently as a

snowflake, alighted thereon and pirouetted without causing the hand

to shake.

There were some really wonderful tableaux "The Valley of Ferns," "Egypt,

" "India," "Japan," "The Parisian Rose

Garden" and "The Triumph of the Fan."

The last-named was the most gorgeous of all; hundreds of people on

the stage, many in hand-painted costumes and waving scores of huge

fans of ostrich plumes; greater fans of lace and feathers appearing

from flies and wings, all illuminated with colored electric bulbs;

and above all, the seven aerial dancers, each poised on the points

of an illuminated glass star which revolved under the touch of her

toes. Some of those fans caught fire at Cleveland and came near

precipitating a calamity, but happily were extinguished betimes.

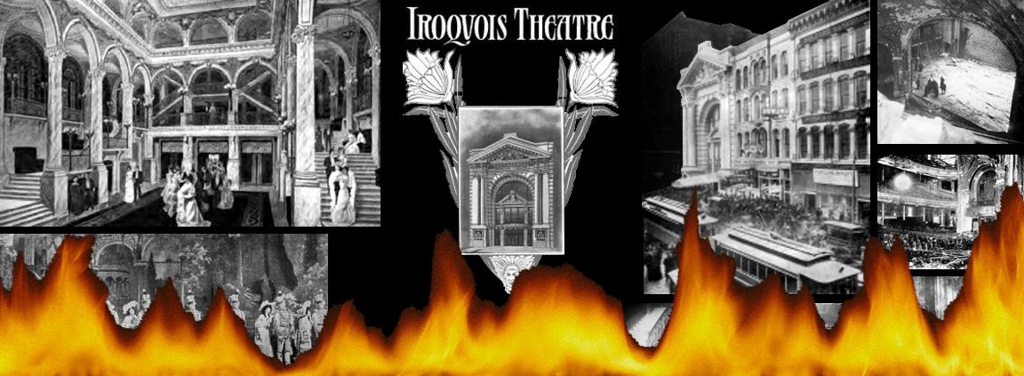

"Mr. Bluebeard" opened the new Iroquois Theatre in

Chicago on November 23, 1903. They made a great celebration of the

opening, had elaborate souvenir programs and no little ceremony.

The two local stockholder-managers of the theatre, the architect of

the building and one or two others made speeches, and certain of the

gallery gods called loudly for an oration from me, but the orchestra

mercifully drowned their outcries by striking up "America."

The theatre was one of the finest that had yet been built in this country, a palace

of marble and plate glass, plush and mahogany and gilding. It had a

magnificent promenade foyer, like an old-world palace hall, with a

ceiling sixty feet from the floor and grand staircases ascending on

either side. Backstage it was far and away the most commodious I had

ever seen. The space in the rear allowed for enormous expansion of

the stage setting. They must have had as much room back there as, or

more than they have in the Metropolitan Opera House in New York. A

vast expanse of dressing rooms was provided under the stage and

auditorium for the chorus, and the principals dressed on the stage

level or above. The flies were reached by elevators. We were told

that the theatre was the very last word in efficiency, convenience,

and safety. Instead, it proved to be a fools paradise. There had

been no great theatre disaster in this country for many years, and

all precautions against such a thing were greatly relaxed.

Chicago having been our home for so many years, I had taken my wife and children

with me on this trip and we were stopping at the Sherman

[hotel]. We had an uproarious time with

the kids around the holiday season. My mother, then nearing eighty,

was not too old to join in the fun. Business was good at the

theatre, and life in general seemed to be moving along very

satisfactorily.

We drew big crowds all through Christmas week. On Wednesday afternoon, December 30th,

at the bargain price matinee, the house was packed and many were

standing. I tried to get passes for my wife and youngsters, but

failed. It was then decided that I should take only the eldest boy,

Bryan, aged six, to the show and stow him wherever I could. I tried

to get a seat for him down in front, but found that there were none

left, so I put him on a little stool in the first entrance at the

right of the stage, a sort of alcove near the switchboard, and he

liked that even better than being down in the seats.

It struck me as I looked out over the crowd during the first act that I had never

before seen so many woman and children in an audience. Even the

gallery was full of mothers and children. There were several parties

of girls in their teens. Teachers, college and high school students

on their vacations were there in great numbers. The house seated a

few more than 1,600. The managers declared afterwards that they sold

only a few more than a hundred standing room tickets, which would

bring the total attendance to considerably over 1,700. The

testimony of others seemed to indicate that there were many more

standees than admitted by the management, and it was widely believed

that there were more than 2,000 people in the house that afternoon.

And remember that back of the curtain, counting the members of the

company, stage hands and so on, there were fully 400 more. The

quantity of scenery, costumes and properties required for such a

spectacle is prodigious, and a big force of men and women besides

the actors is necessary to take care of it.

Much of the

scenery used was of a very flimsy character. Hanging suspended by a

forest of ropes above the stage and so close together that they were

well-nigh touching each other were no less than 280 drops, several

of which were necessary to each set; all painted with oil colors,

the great majority of them cut into delicate lacery and some of them

of sheer gauze. There had been a fire in the scenery during our

engagement in Cleveland, but by a piece of luck it was quickly

squelched; and I had been playing in theatres for so long without

any trouble with fire that the incident didn't give me much of a

scare. It takes a disaster to make one cautious. After our

experience at the Iroquois, not one in ten of us actors (and I dare

say other people would have been equally heedless) could remember

whether we had ever seen any fire extinguishers, fire hose, axes or

other apparatus back of the stage.

The play went merrily through the first act. At the beginning of the second act a

double octet of eight men and eight women had a very pretty number

called "In the Pale Moonlight." The stage was flooded with bluish

light while they sang and danced. It was then that the trouble

began. In spite of some slight conflict of opinion, there can be no

doubt that one of the big lights high up at one side of the stage

blew out its fuse. That was what had caused the Cleveland blaze, and

it was well known to the electricians of the company that in order

to obtain the desired lighting effects, they were carrying much too

heavy a load of power on the wires. Anyhow, a bit of the gauzy

drapery caught fire at the right of the stage, some twelve or

fifteen feet above the floor.

I was to come on in a few minutes for my turn with the comic elephant, and I was in

my dressing room making up, as I wore a slightly different outfit in

this scene. I heard a commotion outside and my first idle thought

was, "I wonder if they are fighting down there again" for there had

been a row a few days before among the supers and stage hands. But

the noise swelled in volume, and suddenly I became frightened. I

jerked my door open, and instantly I knew that there was something

deadly wrong. It could be nothing else but fire. My first thought

was for Bryan, and I ran downstairs and around into the wings.

Probably not forty seconds had elapsed since I heard the first

commotion but already the terror was beginning.

When the blaze was first discovered, two stage hands tried to extinguish it. One of

them, it is said, strove to beat it out with a stick or a piece of

canvas or something else, but it was too far above his head. Then he

or the other man got one of those fire extinguishers consisting of a

small tin tube of powder and tried to throw; the stuff on the flame,

but it was ridiculously inadequate. If there were any of those large

fire extinguishers there which throw liquid chemicals from a hose,

nobody seemed to find them or to think of them.

|

|

Meanwhile in the

audience, those far around on the opposite side and especially those

near the stage could see this blaze and the men fighting it, and

they began to get frightened.

The flame spread through those tinder-like fabrics with terrible rapidity. If

the drop first ignited could have been instantly separated from the

others, the calamity might have been averted; but that was

impossible.

Within a minute the flame was beyond possibility of control by anything but a fire

hose. Probably not even a big fire extinguisher could have stopped

it by that time. Why no attempt was made to use any such apparatus,

or whether, indeed, it was in working order, I don't know. If the

house force had ever had any fire drills, there was no evidence of

it in their actions.

The stage manager was absent at the moment, and several of the stage hands were in a

saloon across the street. No one had even taken the trouble to see

that a fire alarm box was located on or near the theater, and a

stage hand ran all the way to South Water Street to turn in the

alarm.

As I ran around back of the rear drop, I could hear the murmur of excitement growing

in the audience. Somebody had of course yelled "Fire!" there is

almost always a fool of that species in an audience and sometimes

several of them; and there are always hundreds of poorly balanced

people who go crazy the moment they hear the word. I ran around

into the wings, shouting for Bryan.

The lower borders on that side were all aflame, and the blaze was leaping up into the

flies. On the stage those brave boys and girls, bless them, were

still singing and doing their steps, though the girl's voices were

beginning to falter a little. I found my boy in his place, though

getting much frightened. I seized him and started towards the rear.

But all those women and children out in front haunted me, the

hundreds of little ones who would be helpless, trodden under foot in

a panic. I must do what I could to save them I tossed Bryan into the

arms of a stage hand, crying "Take my boy out!" I paused a moment

to watch him running towards the rear doors; then I turned and ran

out on the stage, right through the ranks of the octet, still

tremblingly doing their part, though the scenery was blazing over

them; but as I reached the footlights, one of the girls fainted and

one of the men picked her up and carried her off. I was a grotesque

figure to come before an audience at so serious an occasion, in

tights and comic shoes, a short smock, a sort of abbreviated Mother

Hubbard, and a wig with a ridiculous little pigtail curving upward

from the back of my head. The crowd was beginning to surge towards

the doors and already showing signs of a stampede with those on the

lower floor not so badly frightened as those in the more dangerous

balcony and gallery. Up there they were falling into panic.

Oh, God, if only I possessed an overmastering personality and eloquence that could

quiet them! If only I could do fifty things at once! "Why didn't the

asbestos curtain come down?" I began shouting at the top of my

voice, "Don't get excited. There's no danger. Take it easy!" and to Dillea, the orchestra leader, "Play! Start an overture, anything!

But play!" some of his musicians were fleeing, but a few, and

especially a fat German violinist, stuck nobly . "Take your time,

folks!" (Wonder if that man got out with Bryan?) "No danger!" And

sidewise into the wings, the asbestos curtain! For God's sake,

doesn't anybody know how to lower this curtain? "Go slow, people! You'll get out!"

I stood perfectly still, and when addressing the audience spoke slowly, knowing that

these signs of self-possession have a calming effect on a crowd.

Those on the lower floor heard me and seemed to be reassured a

little, but up above and especially in the gallery, self possession

had fled; they had gone mad.

Down came the curtain slowly, two-thirds of the way and stopped, one end higher

than the other, caught on the wire on which the girl made her flight

over the audience, [Inaccurate. No

aerialist wire was involved. The curtain caught on a lamp hinged

to the north side of the proscenium arch. Eddie was not on stage when

the fire broke out and apparently didn't read newspaper coverage of the

subsequent trials in which a dozen stage workers testified about the

curtain becoming caught on a side lighting fixture.] and which had

just been raised into position

for the coming feat. Then the strong draught coming through the back

doors by which the company were fleeing, bellied the slack of it in

a wide arc out into the auditorium, letting the draft and flame

through at its sides. "Lower it! Cut the wire!" I yelled. "Don't be

frightened, folks! Go slow!" (Oh, God, maybe that man didn't take

Bryan out!) "No danger! Play, Dillea!"

Below me, Dillea was still swinging his baton and that brave, fat little German was

still fiddling alone and furiously, but no man could hear him now,

for the roar of the flames was added to the roar of the mob. In the

upper tiers they were in a mad, animal-like stampede, their screams,

groans and snarls, the scuffle of thousands of feet and of bodies

grinding against bodies merging into a crescendo half-wail, half

roar, the most dreadful sound that ever assailed human ears.

Then came a cyclonic blast of fire from the stage out into the auditorium,

probably a great mass of scenery suddenly ignited and fanned by a

stronger gust, a flash and a roar as when a heap of loose powder is

fired all at once. A huge billow of flame leaped out past me and

over me and seemed to reach even to the balconies. Some of the

audience described it as an "explosion" and "a great ball of fire."

A shower of blazing fragments fell over me and set, my wig

smoldering. A fringe on the edge of the curtain just above my head

was burning, and as I glanced up, the curtain itself was

disintegrating. It was thin and not wire-reinforced; another cheat!

Now the last of the musicians had fled. I could do nothing more, and I might as well

go, too. But by this time

the inferno behind me was so terrible that I wondered whether I

could escape that way; perhaps it were better through the

auditorium. But Bryan had gone out by the rear, if he had gone at

all, and I was irresistibly drawn to follow, that I might learn his

fate more quickly. I think I was the last man on the stage; I fairly

had to grope my way through flame and smoke to reach the Dearborn

Street stage door, which was still jammed with our people getting

out. The actors and stage employees nearly all escaped, saved

by the failure of the asbestos curtain to come down, which let the

bulk of the flame roll out into the auditorium and brought death to

many in the audience. The flying ballet went out as I did, rescued'

by the heroism of the elevator boy, who ran his car up through tips

of flame into the flies where they stood awaiting their turn, and

brought them down. But one of them, Nellie Reed, the premiere, was

so badly burned that she died in a hospital a day or two later.

Some of the people dressing

under the stage had to break down doors or escape through coal

chutes.

As I left the stage the last of the ropes holding up the drops burned through, and

with them the whole loft collapsed with a terrifying crash, bringing

down tons of burning material, and with that, all the lights in the

house went out and another great balloon of flame leaped out into

the auditorium, licking even the ceiling and killing scores who had

not yet succeeded in escaping from the gallery.

The horror in the auditorium was beyond all description. There were thirty exits, but

few of them were marked by lights, some even had heavy portieres

over the doors, and some of the doors were locked or fastened with

levers which no one knew how to work. There was no great panic on

the parquet floor save at the outskirts, and I am humbly thankful in

the belief that my pleading quieted those within the sound of my

voice and prevented those nearest the stage (although in greater

danger) from throwing their weight against those massed near the

doors. There was a bit of a stampede at the rear of the ground

floor, among those less in danger than any others in the house, and

some were trampled underfoot, but most of them were rescued by the

determined efforts of the door-keepers and policemen at the

entrances.

It was said that some of the exit doors leading from the upper tiers on to the fire

escapes on the alley between Randolph and Lake Streets seemed to be

cither rusted or frozen (for the weather was bitterly cold) and were

very hard to open. They were finally burst open, but meanwhile

precious moments had been lost which meant the death of many behind

those doors. The fire escape ladders could not accommodate the

crowd, and many fell or jumped to death on the pavement below. Some

of those following were not killed because they alighted on the

cushion of bodies of those who had gone before. When one balcony

exit was opened, those who surged out on the platform found that

they could not descend the steps because flames were leaping from

the exit below them.

Some painters in a building across a narrow court threw a ladder over to the platform;

a man started crawling over it, one end of it slipped off the icy

landing and he fell, crushed, on the stones below. The painters then

succeeded in bridging the gap with plank, and just twelve people

crossed that narrow footpath to safety.

|

|

The twelfth was

pursued by a tongue of flame which dashed against the wall of the

opposite building, and no more escaped.

The iron platform

was crowded with women and children. Some died right there; others

crawled over the railing and fell to the pavement. The iron railings

were actually torn off some of the platforms.

[Torn-away railings is information not

published elsewhere.]

But it was inside the house that the greatest loss of life occurred, especially on the

stairways leading down from the second balcony. Here most of the

dead were trampled or smothered, though many jumped or fell over the

balustrade to the floor of the foyer.

In places on the stairways, particularly where a turn caused a jam, the bodies were

piled seven or eight feet deep. Firemen and police confronted a

sickening task in disentangling them.

An occasional living person was found in the heaps, but most of these were

terribly injured. The heel prints on the dead faces mutely testified

to the cruel fact that human animals stricken by terror are as mad

and ruthless as stampeding cattle. Many bodies had the clothes torn

from them, and some had the flesh trodden from their bones.

Never elsewhere did a great fire disaster occur so quickly. It is said that from the

start of the fire until all the audience were either escaped or

killed or lying maimed in the halls and alleys the time was just

eight minutes. In that eight minutes more than five hundred lives

went out. The fire department arrived quickly after the alarm and

extinguished the fire in the auditorium so promptly that no more

than the plush upholstery was burned off the seats, the wooden parts

remaining intact But when a fire chief thrust his head through a

side exit and shouted, "Is anybody alive in here?" Not a sound was

heard in reply. The few who were not dead were insensible or dying.

Within ten minutes from the beginning of the fire, bodies were being

laid in rows on the sidewalks, and all the ambulances and

dead-wagons in the city could not keep up with the ghastly harvest.

Within twenty-four hours Chicago knew that at least 587 were dead,

and that many more injured. Subsequent deaths among the injured

brought the list up to 602.

As I rushed out of the theatre, I could think of nothing but my boy. I became more and

more frightened; as I neared the street I was certain he hadn't

gotten out. But when I reached the sidewalk, God be praised, there

he was with his faithful friend just outside the door. I seized him

in my arms and turned toward the hotel.

It was a thinly clad mob which poured out of the stage doors into the snow. The

temperature was around zero, and an icy gale was howling through the

streets. Many of the actors and actresses had had no opportunity to

save street clothes or wraps, and some of the chorus girls who were

dressing at the time of the fire were compelled to run out almost

nude. Kindly people furnished wraps for these whenever they could

and took them into business houses nearby for refuge. My own outfit

of tights and thin smock felt like nothing at all, and my teeth were

chattering so from the cold and the horror of what I had just been

through that I could not speak. A well-dressed man, a stranger to

me, stopped me and said, "My friend, you'd better borrow my overcoat, "

throwing off his heavy coat as he did so and helping me

to put it on. He then picked up Bryan and walked with me across the

street, and there, at the corner of a drug store, hurrying towards

the theatre, I saw my wife with the two youngest children.

She gave a scream at sight of me, and crying, "Oh, thank God!

Thank God!" she threw herself into my arms, then seized Bryan

and kissed him, then me again, transferring quantities of grease

paint from my face to her own and then to her son's. She had

had a vague premonition of disaster from the time that Bryan and

I had left the hotel that afternoon. Her ears unconsciously alert

for significant sounds, she had heard the first clang of a fire truck

gong in the street and rushed to the window, saw the direction the firemen were taking, and

felt certain that the trouble was at the theatre. Quickly she put

wraps on the children and started towards the Iroquois on foot.

We turned back towards the hotel, thankful yet horrified, for I knew that the

calamity must have been a terrible one. I returned the overcoat to

my good-Samaritan friend, but was so agitated that I forgot to ask

his name or even to thank him adequately, I fear. If he still lives

and chances to read this, I hope he will understand and accept this

belated expression of my gratitude.

I had no sleep at all that night. Newspaper reporters were begging me for interviews,

friends were calling me by telephone and wiring me, and I had to

reassure my mother and sisters, and my wife's two sisters, who were

taking care of our Eastern home. I was too excited to sleep, anyhow,

even if I had had opportunity. My nerves did not subside to normal

pitch for weeks afterward.

I was greatly touched by the many kindly things spoken by the press regarding my

behavior in the disaster. What I did was little enough. Heaven

knows, and at the critical moment I was enraged almost to the point

of madness because of my inability to do more.

The Iroquois disaster brought about a serious reaction upon the theatrical

profession in general. On the day after the fire every theatre in

Chicago was closed, and they remained so for some time, while the

city authorities were investigating the question of their safety.

Numerous road shows were thus thrown out of weeks of business in

Chicago, and to make it worse, New York and other cities also began

closing theatres suspected of being unsafe. Theatre managers the

country over of course began rushing into print with declarations

that a disaster like that of the Iroquois could not possibly happen

in their house; but city governments generally refused to accept

such statements until they had been put to the test.

A New York newspaper a few days later listed over fifty companies which had

actually closed their season's run; and it was said that counting

vaudeville and burlesque players there were 15,000 people idle. In

Chicago alone during the first two weeks in January 6,000 who

depended upon the mimic world for their living, actors, actresses,

chorus singers, stage hands, mechanics, etc. were out of work.

But the terrible lesson was sadly needed. In New York at that very moment there were

Broadway theatres which had wooden stairways; there were aisles so

narrow that not more than one person could pass through them at a

time; the matter of exits had been given little study or even

attention; there was a theatre located upstairs in that city with

only one not too wide stairway, and a winding one at that, down

which the entire audience must go to reach the ground; there were

basement dressing rooms reached by stairways little better than

ladders, where actors would be caught like rats in a trap in case of

a sudden fire. The fine for violation of the fire laws in New York

was nominal. The retiring fire commissioner of that city had

recently asserted that there were theatres on Broadway which were

far worse traps than the

Iroquois. During the discussion which prevailed, Oscar Hammerstein declared that no

children would ever be admitted to a theatre controlled by him; and

he angered some of the ladies by adding that a woman with a child

constituted one of the most dangerous elements that could be found

inside a theatre. [Yep, we silly goose

mothers get right excited when our child's hair is afire and he will

die in our arms.]

The Chicago horror was a blessing in one respect, namely, in that it brought about a

country-wide investigation and house-cleaning. Theatres in some

cities were declared hopeless fire-traps and were permanently

closed. Others were compelled to make costly repairs. The top

gallery of a theatre in Philadelphia was eliminated. Stringent

ordinances regarding exits were passed and enforced. A Boston

theatre manager, anxious to prove the safety of his house, threw it

open during the day and invited the public to call and inspect the

aisles and exit arrangements and to test the asbestos curtain with a

plumber's blowtorch. Since then theatres have been far safer than

ever before. There are occasional hazards and violations of the laws

of safety still, but I hope and believe that another disaster such

as that of the Iroquois is at least improbable.

The Mr. Bluebeard production was totally ruined, and Klaw & Erlanger soon decided that

they would not attempt to reproduce it; so about three hundred

people were for the time being thrown out of jobs. I went back East

with my family and for a few weeks did an act in vaudevillian

adaptation of my scene between Sister Anne and the elephant. I had

the same two young men who had played the fore and hind legs of the

animal in the Bluebeard company, but I had to get a new

elephant, as the old one had been cremated in the fire.

|