|

Elizabeth

One of the most disturbing Iroquois Theater

fire stories. In researching this young girl's story I found myself

wishing for a last-minute rescue of a type seen in movies.

In the 2003 book Tinderbox, author Anthony Hatch relates a story told

to him in 1961 by a retired Chicago fireman who was among first responders

at the Iroquois. Eighty-nine-year-old Michael J. Corrigan (1872-1966)

described receiving a surprise while working to remove the dead from the

Iroquois theater.

As painting contractors had done, Chicago

firemen made a bridge of a ladder stretched from the dental department at

Northwestern University to

door

#37 at the Iroquois. That door led from the back of the third-floor

balcony to the eastern-most fire escape. A majority of the audience in the

third-floor gallery had converged in the standing room area behind the

seats. There were masses of victims on the south side at the doors leading

to the lobby (door nos 38 & 39) and on the north side at the doors leading

to the fire escapes (door nos 35-37). When the fireball hurled from the

stage into the auditorium, most died instantly. Feet and legs held partly

upright, rooted in the densely packed crowd, upper bodies fallen sideways

haphazardly. Several first responders described the arrangement of bodies as

looking like Timothy grass.

Interior stairwells and balcony doorways were piled

high with victims, impeding fire fighter's access. To put out the last of

the fire and search for survivors, firemen had to clear a path through the

bodies. Some were dropped to the ground sixty feet below. Over a hundred

were carried across the ladder to Northwestern.

As the firemen worked amidst hundreds of dead, a semi-clad girl, blackened

with burns and soot, rose specter-like from between the rows of seats.

According to Corrigan, she ran toward the fire escape exit and across the

ladder into Northwestern, firemen chasing after her with a blanket.

I have no doubt that girl was thirteen-year-old* Elizabeth "Bessie"

Ricketts Clingen (b.1890). While she may have run toward the open door, and

whatever dim light and cold air streamed through it, she did not run across

a narrow plank. Bessie was sightless, her eyes destroyed by the fire.

Elizabeth's eventual obituary, on February 11, 1904, contained discrepancies

depending upon the newspaper — one reporting she was found beneath a pile of

bodies and another beneath the seats. All reports agreed she

was carried across a plank to Northwestern by firemen. Walking across a

twenty-foot plank sixty feet off the ground would take great courage. Doing

it while carrying a body is the stuff of heroes.

Elizabeth's later obituary reported she attended the theater with two

companions, with no mention of their identities or if they survived. I kept

delving and learned that one of the companions was Elizabeth's younger

sister, twelve-year-old Margaret Edith "Effy" Ricketts Clingen (1891-1918).

I suspect the third party member was the girls' mother, for whom Elizabeth

was named, Elizabeth Caroline Bowen Clingen, and that she escaped from the

theater with the younger child, Margaret.

Then came Grandma Lizzie

At the time of the 1900 census, and until

1901, Elizabeth and and her sister lived with their grandparents in Decatur,

IL, 180 miles southwest of Chicago. The grandparents were William L. Newman

(1838-1914) and Pennsylvania native, Kate "Lizzie" E. Shank Bowman Newman

(1850-1940). By 1903 the sisters were living in Chicago with their mother and

stepfather and used their stepfather's name, Clingen, instead of their birth

name, Ricketts. It was a common practice of the time for children to assume

a stepfather's name, without evidence of a legal adoption procedure. When a

man married, his wife and her children became his property.

William Clingen's failure to immediately cable the Newman grandparents with

the sorry news of their granddaughter's hospitalization is understandable.

The girls were in two different hospitals and he did not locate Elizabeth

until the day after the fire. It is not known when Margaret was released

from the hospital. If their mother was also at the theater, nothing is known

of her condition.

William had an additional reason to do some foot-dragging in contacting his

mother in law. He had agreed with a decision of his wife, a devout Christian

Scientist, that was sure to incur Lizzie's wrath. They'd removed Elizabeth

from the hospital and turned her care over to a faith healer. They believed

God would do what was best for Elizabeth. As it happened, Lizzie Newman had

also been communing with God and asserted the book she was writing on the

subject of Satan's involvement in Christian Science and faith healing was at

His direction. Elizabeth became caught in her family's contradictory

interpretations of God's will.

Lizzie accepted the inevitability of her granddaughter's death but condemned

her daughter for preventing Elizabeth from taking medication that could

relieve her pain.

Read more about Lizzie below.

|

|

More details about Elizabeth's rescue

Elizabeth and her companions were seated or standing in the third-floor

balcony. As the audience fought to reach safety, Elizabeth fell to the

floor.

Surrounded by seats and/or, depending upon the

obituary, layered beneath other people, she was somewhat protected from the

fireball. Enough to survive while many others perished at the scene, but not

enough to prevent mortal injuries.

Elizabeth was transported to the

Passavant Hospital

where she was probably given opioids during the most painful first hours,

before her mother could interfere. Reportedly Elizabeth's stepfather,

William C. Clingen, heard about the fire and reached the front doors of the

Iroquois Theater about the same time that Elizabeth was being rescued.

Elizabeth tried to conceal her pain from her mother

Passavant physicians did what they could for Elizabeth but advised the

parents that their daughter would not survive. One obituary said Elizabeth

insisted upon going home the second day. Since newspaper reports also noted

she accommodated her mother's belief in faith healing, her interest in

leaving the hospital may have been motivated by a wish to please her mother.

To physicians, she privately confessed that the pain was awful. Her burns

probably varied from second to third degree, the worst injuries at the

extremities. Since she was not expected to live, treatment would have been

limited to pain management. The areas with least nerve damage were probably

the most painful.

Skin on ears and toes sloughed away

Elizabeth was initially taken to her home at

291 Ashland Blvd. For the next forty days the teenager received no

medication. Her burns were treated with olive oil† and she was told her pain

did not exist, that she would recover if she put her faith in God.

Elizabeth's suffering hidden from protesting neighbors and authorities

Pressure came from neighborhood nurses and the health

department to re-hospitalize the girl. They may have been alerted by

Elizabeth's screams, as were the neighbors of another Iroquois victim, who

had received pain killers, whose screams could be heard in neighboring

homes. Elizabeth's parents transferred her to a so-called hospital that was

a former laying-in home for pregnant women, operated without physicians, by

a Christian Science midwife who had no training in caring for burn

victims.

Like moving her from the Passavant Hospital, the decision to be moved away

from her home, was attributed to Elizabeth. (Read more

about her care below.)

Elizabeth's parents

Stepfather William C. Clingen (1862-) was from

Detroit. Her mother, also named Elizabeth, (by the end of her life her full

name being Elizabeth Caroline Bowen Ricketts Clingen and nicknamed Bessie

and Effie (1872-1959), was from Iowa. They had married in 1899 in Milwaukee,

WI. William was Bessie's second husband. In 1894 she divorced her first

husband, Elizabeth and Margaret's father, butcher Harry J. Ricketts

(1869-1913), citing adultery and extreme cruelty.

In the years after the fire

By 1908 William and Bessie lived in Lake

Bluff, Illinois, where he invented and patented a fireless cooker. They

eventually divorced. In 1920 William remarried divorcee Lina Plumer Wamboldt.

Bessie left the Christian Science faith and became a

Moravian.

Grandmother Lizzie and William Newman lived in Joplin, Missouri at the end of

their lives.

I found nothing to indicate whether there was a reconciliation between Lizzy

and her daughter or whether Margaret Ricketts Clingen joined the Christian

Science faith as an adult. their lives.

I found nothing to indicate whether there was a reconciliation between Lizzy

and her daughter or whether Margaret Ricketts Clingen joined the Christian

Science faith as an adult.

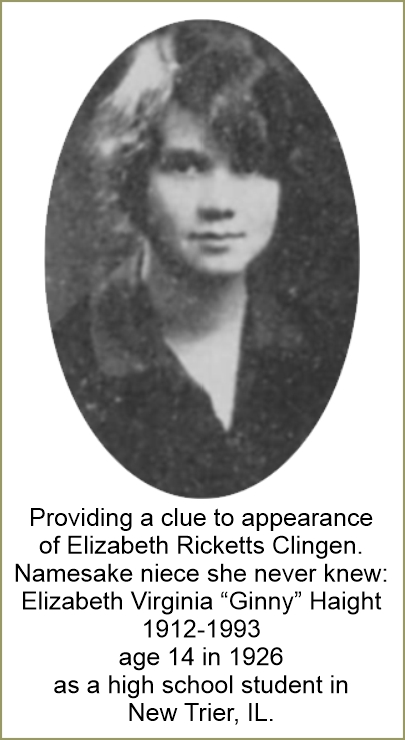

Elizabeth's younger sister, Margaret Edith Ricketts Clingen, attended Parsons college, married Abram Van Voorhis Haight

II. They had two children and lived in

Evanston, Illinois when she died in 1918 at age twenty-seven. She

named her daughter after her mother and late sister: Elizabeth Virginia Haight (1912-1993).

Nicknamed Ginny, the daughter participated in basketball and volleyball, in the

orchestra and school newspaper, and in the drama club, acting in four plays

one year. The accompanying picture might be the only clue as to the

appearance of her aunt Elizabeth Rickets Clingen. |