|

nearly six hundred members of

the Iroquois Theater audience would lose their lives

that afternoon, but few fatalities or serious

injuries came from first-floor seats. Many

from there, like the Phillipson party, lost nothing

but their coats. Lillian, the youngest, became

separated from the family and was briefly thought to

be a victim. According to one newspaper, the

girl made it to the Union Hotel (probably referring

to the Grand Union Hotel in the former Music Hall

building on Randolph street) then somehow found her

family. Other stories connected the Phillipson

family to the more distant Continental Hotel. There

were many discrepancies in reports about the

family's Iroquois experience, but the appearance of

Lillian's name on missing lists suggests she was

missing for a few hours.

Many errors

Some newspapers reported there were three rather than

four Phillipson daughters. Francis became Florence. Flora

was at the Continental hotel sobbing for her children as others

searched for them in area stores, but she found

Lillian in a drugstore, dead, and left her there (!)

All three girls were missing; only Lillian was

missing. By some reports Flora's hysteria

might have contributed to erroneous information. If

so, it was a temporary response to her fear. A

lifetime of shrewd business activity says Flora

Phillipson was not a flibbertigibbet.

Flora

I've failed to learn much

anything about Flora's childhood. She was the

daughter of immigrants Joseph and Theresa Marks, and

had at least two siblings, Isaac and David. One

story stated she was from Philadelphia but the 1900

U.S. Census reported she was born in New York. The

same census has Joseph emigrating in 1875 but his

naturalization filing reported 1867. Flora might

have had a fuzzy recollection of when Joseph

emigrated, and Joseph might have been mistaken about

the state of Flora's birth but another possibility

is that the oldest daughter, Francis, then sixteen,

supplied the information to the census enumerator.

Team Flora and Joseph

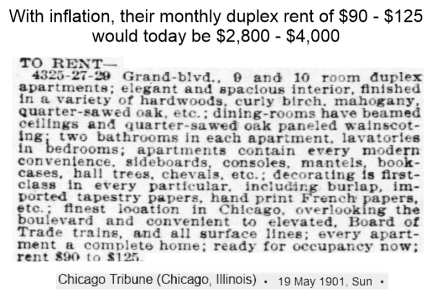

Married in 1882 to Joseph Phillipson (1861-1906), Flora's

family in 1903 lived in a ten-room duplex at 4325-27 Grand Blvd in

the Humboldt Park neighborhood in northwest Chicago.

Joseph continued doing business on the near west

side. He employed Polish-speaking workers and his

customers were as familiar as family. The series of

Phillipson dry goods stores from 1882 to 1906 were

located in this Maxwell street area, called "the

ghetto," where his parents, Phillip and Rachel

Phillipson, settled after immigrating from Poland

c.1867. It was there that Joseph and his brother,

Samuel Phillipson (1866-1936), had worked as

teenagers, learning the dry goods peddling business

from the ground up by helping their father peddle

merchandise door to door, carrying packs on their

backs. It was there that Flora, yet a bride, helped

Joseph work the peddling wagon and in 1882 urged him

to set up his first store, a 14 x 20 structure at

491 S. Jefferson St. that sold notions at retail and

wholesaled to other peddlers. Reportedly Joseph

credited Flora as critical to his success. In the

early years and again during the 1893 depression,

she served as saleswoman, janitor, bookkeeper, and

secretary.

The first new construction for a Phillipson store

was in 1897 at the southwest corner of Jefferson and

Dussold, a $35,000 four-story building designed by

Cowles & Ohrenstein. It was attached to an existing

structure, producing an 85'x125' store.

Three years before the Iroquois fire, Joseph had

leased a building on Chicago's Jefferson and O'Brien

streets. It had been the city's only Yiddish

playhouse and the manager of the theater was angry

to be ejected, but Joseph prevailed and annexed the

structure to their six-story dry goods store facing

Jefferson. The store was described as the first big

department store in the "ghetto."†

|

Both Flora's husbands kept such low profiles in the

media that learning about them is

difficult - and for a man with as many

employees and business associates as

Joseph Phillipson, such aversion to

publicity was unusual.

So much so that I went looking for an

explanation and may have found a clue in

a description of Flora's second husband.

About Samuel Zwetow it was said that he

abided by the Talmud and avoided

aggrandizement. Perhaps Flora was

drawn to that characteristic in Sam as

she had been to it in Joe thirty-eight

years earlier.

Aggrandizement do thou avoid!

A name made great's a name destroyed.

Aboth I.13 (1894 Isadore Myers

translation of the Talmud)

|

In the years after the fire

A year after the Iroquois fire, Joseph took out a ten-year loan to

build a new $150,000 store on the northeast corner

of Halsted and Twelfth. It was described as a sign

that merchants were ready to bring big State street

type department stores to distant neighborhoods. He

lived to see it in operation for only a few months.

A brief obituary notice stated that a fuller

obituary would follow but I failed to find it. He

was in Hot Springs at the time, presumably in

Arkansas, perhaps trying to treat an ailment.

|

|

Three years and three days after the Iroquois

Theater fire, Flora purchased a box seat at the

Coliseum Theater to attend a benefit for the Jewish

Old People's Home on Albany and Ogden avenues. She'd

been active in Jewish society from the early days of

her marriage, serving as vice president of the

Hebrew Ladies Aid Society in 1890, but the Jewish

Old People's home was special. Joseph had been one

of the organization's founders, and an officer. He'd

been gone for ten months and Flora, ever the

helpmate, donated $5,000 to the home.

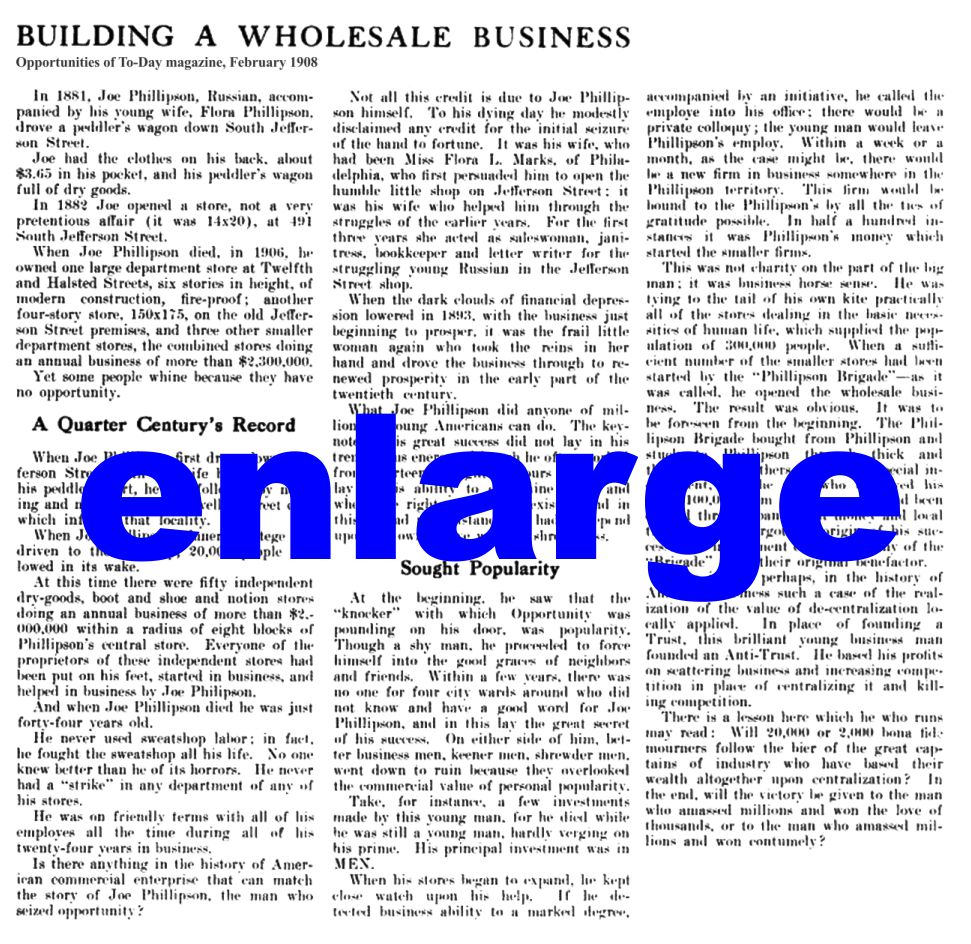

Joe Phillipson exceptional

An estimated 20,000 people joined the February 1906 funeral

entourage for Joseph Phillipson. They were the shopkeepers,

employees and families he'd helped get started over

the prior two decades, resulting in fifty

shopkeepers stores within an eight-block radius of

the Phillipson store.

They included five millinery shops and multiple shoe and

boot stores, generating an estimated $2 million in

annual sales. Many had begun as employees at the

Phillipson store, recognized by Joseph as having

good business sense. Known as the Phillipson

Brigade, they became his loyal customer base

when he later opened a wholesale branch.

They included five millinery shops and multiple shoe and

boot stores, generating an estimated $2 million in

annual sales. Many had begun as employees at the

Phillipson store, recognized by Joseph as having

good business sense. Known as the Phillipson

Brigade, they became his loyal customer base

when he later opened a wholesale branch.

Flora sells Joseph's baby

At Joseph's death. Flora had four daughters aged

thirteen to twenty-two to continue raising and

see wed. She held out for three years, running

the store herself then, in March, 1909, sold the

stock and fixtures of the Joseph Phillipson Department store and the warehouse on

Jefferson and O'Brien, the former site of the

Yiddish theater, for $339,757 ($9 million today)

plus a twenty-year $19,000 annual lease on the

property. It was heralded as the largest deal of its

kind in the ghetto district. The buyers: Henry

Isaacs, owner of Fairbanks department stores in

Alaska and Joseph Weissenbach, son-in-law of Leon

Klein, owner of Joseph's primary competitor, the L.

Klein department store a block away at Halsted and

Fourteenth streets. The new owners changed the name

to "The Twelfth Street Store."

The decision to sell the store may have been

difficult for Flora. She surely considered

continuing to run the store herself. As a woman

living in Illinois, unlike some other states, she

could own property and control her earnings, but it

would have been hard work regardless of gender.

Joseph's store was a much larger entity in 1906 than

it had been when she worked there in 1893. Many more

employees and customers, much more inventory.

And two sets of brothers. There were Joseph's

brothers, Samuel and Louis Phillipson (1874-1941),

and Flora's brothers, Isaac and David Marks. Samuel

had been a silent partner in Joseph's company (a

silence ended after his brother's death when he

seemed to want shared credit for his role in the

venture's success), and Louis was in management.

Both men may have had ideas about a future role.

Isaac L. Marks (1859-1916), had operated a dry goods

store in Brooklyn before he and his wife, Minnie

Smith Marks, relocated to Chicago in 1908. Did Isaac

and David come to Chicago in expectation of having a

role in Joseph's store? In September, after the

sale, Isaac and a third Marks child, David J. Marks,

formed the Marquette Motor Vehicle company to

manufacture automobiles and engines at 3626 S.

Halstead (no connection to the Marquette-Buick),

capitalized with $20,000 that may have come from

Flora. They exhibited at the 1910 & 1911 Chicago

Auto show, and one of their delivery wagon trucks

ran a reliability race that year. Three years later,

they were out of business. Samuel Phillipson started

over with a wholesale company and a retail

department store, Samuel Phillipson & Bro. He

prospered for two decades, but the business failed

during the 1929 Depression. The name of the retail

store suggests Louis was involved but Samuel made a

point of identifying himself as the sole owner. Am

thinking Samuel may have been a bit less orthodox

than Joseph.

It would be interesting to know what factors

motivated Flora to sell Joseph's store. Perhaps

Joseph had built an empire that could only be run

properly by Joseph. Maybe she didn't want to juggle

two brothers and two brothers-in-law. Or maybe Flora

had just had her fill of dry goods and operating a

business. She'd watched her husband die at an early

age so maybe decided to do a bit more living before

her time came.

Flora and her girls moved to the

Chicago Beach Hotel in the Kenwood neighborhood,

a luxury hotel built for the 1893 Columbian Exposition.

In 1919, thirteen years after Joseph's death, at age forty-nine, Flora

remarried, to widower Samuel R. Zwetow, a wholesale

jeweler and insurance broker from Denver - of a

similar age to Joseph and also a Russian immigrant.

(Zwetow is sometimes Americanized to Sweet.) In 1921

they left Denver and returned to Chicago. Both died

in 1929 and were buried next to their respective

first spouses, Flora in Rosehill Cemetery in Chicago

next to Joseph, and Samuel in Denver's Congregation

Emanuel Cemetery next to Annie Rubinsky.

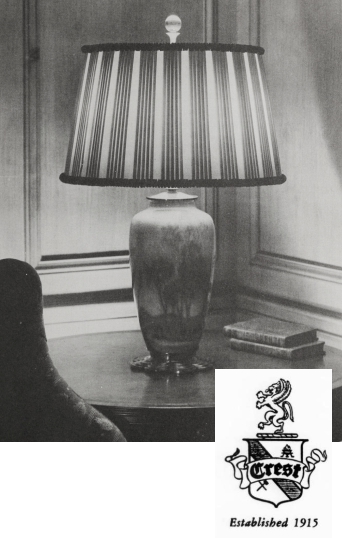

Lillian bore two children with Samuel L. Dinkelspiel

(1891-1961), son of a Louisville cloth and hides

wholesaling family. Samuel became a producer of

antique reproduction furniture and lighting,

including his Legacy Lighting line, examples of

which turn up today at auctions and flea markets.

In 1917 he announced that Crest Company would no

longer manufacture furniture and would concentrate

on floor lamps. Table lamps were added later.

In 1939 the Crest Company table lineup included this Eucalyptus theme Rookwood

Pottery lamp. The vase portion was 14" high with an

8" glass reflector and crystal ball finial. From top

to bottom it was 30.5"c high.

In 1939 the Crest Company table lineup included this Eucalyptus theme Rookwood

Pottery lamp. The vase portion was 14" high with an

8" glass reflector and crystal ball finial. From top

to bottom it was 30.5"c high.

~~~~~~~~~~~

Adeline married grocer Harry Futchenfeld /

Feilchenfeld in 1909

(later shortened to Field) with

whom she had two children, including a daughter

named after Flora.

Francis married jeweler Maurice A. Barnett two and a half years after the fire.

One of their two children was named Joseph, after

his grandfather.‡

Theresa, likely named after her grandmother, Theresa Marks, married

stockbroker Alexander Kieferstein (later

shortened to Kiefer), with whom she had two

children.

|

|

The name Phillipson was sometimes spelled with just one L and

the spelling of Flora's maiden name was sometimes

given as Marx. Frances' name was sometimes spelled

as Francis. Joseph Phillipson employed a manager

named Marks that was perhaps a relative of Flora's.

The Phillipson's had lost four children prior to the

fire, including Ruth who died in infancy in 1899 and

Mark who died at age three in 1889.

Joseph Phillipson's mother, Sarah Rachel, died in 1899 and his father, Philip

Feivel Phillipson (c1830-1903), followed in 1903, six months before the Iroquois

fire. Philip was from Kalwaria Zebrzydowska in

southern Poland. Joseph and Samuel's youngest

brother, Louis, also worked in Joseph's store.

† This1891

description of Chicago's ghetto is filled with

insensitive generalizations of a type that were once

common but helps provide a picture of the

scene in the ghetto when Joseph and Flora Phillipson

were building their business. For a historical

perspective of Chicago's Jewish community, see the

American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise (AICE)'s

Virtual Library discussion. It is not

known what motivated Philip and Rachel Phillipson's

mid 1860s emigration but a

Library of Congress site provides an overview of

the situation in their native country twenty years

later. Just found a copy on Ebay of the 1996 The Jews of Chicago: from shtetl to suburb by

Irving Cutler for $9 including shipping.

You can read an excerpt here.

‡ Maurice Barnett was in 1930 convicted of insurance fraud after

masterminding a 1929 conspiracy with two partners to

stage a fake holdup. He was sentenced to the state

penitentiary for one to five years. Multiple appeals

over thirty-two months kept him out of jail until

November, 1933 when the governor denied his petition

for parole and he was sent to the prison in Joliet.

He was out of jail by Feb, 1936, in time to post

bail for his son in a marital dispute. Maurice and

Francis later moved to Los Angeles.

|

|

What was a dry goods store?

With clothing and textiles as the mainstays, and women as the

primary customers, dry goods stores also

specialized in what we today call house

wares, i.e., dining utensils, cookware, bed

linens and sundries (toiletries, newspapers

and other low priced items). Think

Kohls. Dry goods stores at the turn of

the twentieth century also offered

"everything else" that was either not

offered in such specialty stores as

hardware, grocery, furniture, jewelry,

millinery shops or bookstores, or that was

priced to appeal to shoppers more

constrained by time or budget. A

diamond engagement ring was apt to come from

a jewelry store but a $2 rhinestone brooch

could be picked up during a shopping trip

for a new mackintosh and a replacement sugar

bowl. Hardware stores offered dozens

of hammers for all types of carpentry; dry

goods stores offered a handful of tools for

simple household repairs. In rural

areas with few specialty stores, dry goods

stores made up for it, offering whatever

merchandise the community was willing to

buy. To shopkeepers, the emergence of

mail-order catalog houses such as Sears,

Spiegel and Montgomery Ward must have seemed as

cataclysmic as internet sales have been in

modern times. This 1899

Wrecking House dry goods catalog is one

example.

This 1893-94 Carson Pirie Scott catalog

is an example of a retailer with a

foundation in "bricks and mortar"

trying to get in on the shop-from-home market.

Some of the inventory clusters seem peculiar

— like over two dozen models of accordions and over three

dozen smoking pipes.

|

|