|

Items removed from bodies

Morgues labeled bodies with numbers (toe tags?),

removed and placed valuables in envelopes numbered

to correspond with the body number. The morgues then

turned the envelopes over to police, who delivered

them to the coroner's office.

Items collected from theater

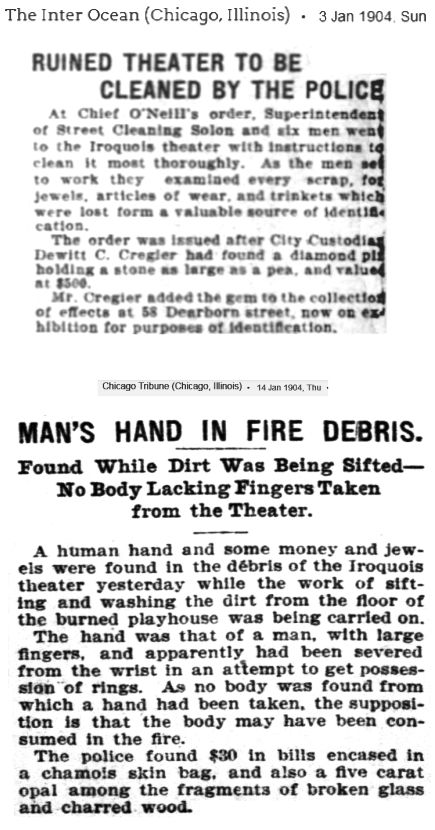

Iroquois ushers began collecting belongings from

the theater immediately after the fire, to prevent

theft by pickpockets and petty criminals who found

their way inside the theater. The grisly task was

soon assigned to the police department. When

Chicago city custodian Dewitt C. Creigier (see right)

found a diamond pin on the floor at the Iroquois with

a stone as large as a pea, its value estimated at $500

($13,000 today), Chicago police chief O'Neill directed

Frank Solon (see right), assistant superintendent of

street cleaning, to take a crew to the Iroquois to

retrieve all personal belongings.

This would have been a job for rakes and shovels

rather than brooms. The floors at the Iroquois were

thick with ashes and soot, turned to mud by water

from fire hoses, then frozen in the unheated

structure by winter temperatures that hovered around

five degrees. Retrieving objects would have required

chopping at the layer of iced soot that covered the

Iroquois floors. Solon's crew scraped and gathered

three wagons full and hauled it to 56-58 Dearborn

street, where Creigier oversaw culling through it

all.

They first picked out clothing, then sifted through

the muck from the floor, using sluicing screens such

as those used in gold panning.

"Minute records of the places in the theater

from which the debris comes, besides the value of

the articles found and other descriptive matter, are

recorded to facilitate absolute identification,"

newspapers reported. *

The tally

The combined tally of belongings removed from bodies

at morgues and scraped from the floors at the

Iroquois was 4,530 items with an estimated value of

$50,000. Of those, owners retrieved 1,617. 764

items were held at the police station awaiting

identification. (The final disposition of those 764

items was not reported.)

Jewelry

Among the belongings was a large array of

jewelry, including fifty diamond rings,

brooches, earrings, watch robs, hatpins, watches

and stick pins. Noted were an 18-stone diamond

ring, 12-stone diamond ring, 3-karat diamond

brooch, 1-karat diamond, ring set with garnets,

amethysts and emeralds, pearl brooch, four unset

gems (2 diamonds and 2 amethysts) and a Grand

Army Republic badge.

Apparel

Clothing, particularly outerwear, comprised the bulk of

the items collected, including 259 coats for

women and girls, 93 for men and boys. The

garments reflected a Chicago winter in the

Edwardian years, including 33 coats of sealskin

and others of astrakhan, otter, mink, lamb, and

bear, with 240 pairs of rubbers, 63 umbrellas,

38 fur boas, 36 fur muffs and 20 fur collars.

Garments also reflected styles of the era with

429 hats (263 womens, 100 girls, 66 men and

boys), 86 side combs and a gold lizard pen. In a

time when shoes had ties and buttons, only 30

pairs were left behind. 195 purses contained

$884.33 in cash and there were 50 opera glasses.

The public could go to a storefront to examine

the items and submit claims. The last item claimed was a small purse by

Adolph Gartz who lost his two young daughters and

five domestic employees at the Iroquois.

Unclaimed property

Creigier kept $280 in unclaimed burned currency and

coins for a year, then turned it over to city

comptroller Lawrence E. McGann, who gave it to the

police pension fund.

2,149 damaged and low-value unclaimed items were

donated to the Salvation Army.

In September 1904, nine months after the fire, a

large pile of unclaimed garments went into the

furnaces at City Hall. As a short news story made

note (see above), some of those garments had

provided clues for victim identification.

Dewitt C. Creigier Jr (1865–1918)

In modern times, the job of a custodian involves

structural maintenance but in 1903 Chicago, the city

custodian took custody of articles and funds

retrieved from thieves or confiscated in police

raids. The son of a former Chicago mayor, Creigier's

annual salary as city custodian was $1,400 ($47,000

today). Earlier

in his career, he'd worked as an electrician and

inventor, patenting a burglar alarm system for

trains.

|

|

Invention was a Creigier

family thing. His father invented a combination fire

hydrant/water fountain/horse trough, and his brother

Nathaniel invented a police communication system.

Dewitt and his wife, Carrie Briggs Creigier, were

active in Chicago's Columbia Yacht Club and owned a

boat named the schooner named Glad Tidings.

Frank W. Solon (1861–1915)

As assistant head of street cleaning, Frank Solon

helped direct roughly 600 workers operating 400

teams of horses in downtown Chicago.

Overseeing the Iroquois clean-up was Frank Solon's

second task. In the hours immediately after the

fire, subsequent to a directive from acting Chicago

mayor Lawrence E. McGann,

William Brennan, acting commissioner of public works,

sent word to police chief O'Neill and

fire marshall Musham that the public works department

was at their service.† Musham responded quickly: "We

need men and lanterns." Brennan sent Frank Solon to

Bullard and Gormley department store to purchase

lanterns. Doherty assembled 150 men working in the

street department in the First ward at the city yard

at the foot of Randolph street with seventy wagons.

Cleaning belongings from the floor at Iroquois Theater

In the years after the fire

A survivor of the fire,

Charles W. Allen, was a long-time friend of the

Creigier family. Six years after the fire, Dewitt

Creigier's mother was arrested by New York Customs

service for smuggling jewels as she returned from

a lengthy European tour with the Allen family. Ella

Allen, Charles's wife, was the one found with jewels

concealed on her person so paid the fine. Charles

Allen and the Creigier family remained friendly,

and in fact Dewitt met with Charles the afternoon

of Charles' accidental death.

|

|

Discrepancies and addendum

Creigier's name was miss-spelled as Cregier, Creiger

and Creger.

* Since nothing was recorded about the location

of bodies, the location of possessions was

helpful only in situations where tickets were

puchased in advance and family members knew the

seats their loved ones occupied.

† Lawrence E. McGann (1852–1928) and William F.

Brennan (1860–1922)

McGann immigrated to

America as a three-year-old with his mother a year

after his father's death. They settled in

Massachusetts initially and moved westward to

Chicago in 1864. He left the cobbler's trade behind

to become a city clerk in 1879. By 1885 he was

superintendent of streets. He served one term in the

U.S. House of Representatives then returned to

Chicago to work as superintendent of the Chicago

General Railway. Mayor Harrison appointed him

commissioner of public works in 1897 and 1899, and

City Comptroller in 1901. Harrison's successor,

Mayor Dunne, though McGann was a Democrat,

reappointed him. On December 30, 1903, in mayor

Harrison's absence, as acting mayor, McGann's

directive to subordinates and department heads:

"You are instructed to direct the fire marshal, chief of

police, and commissioner of public works to proceed

in this emergency without any restriction whatever

with regard to expense in caring for the people. Do

anything needful, spend anything you want, in this

cause, and look to the council for support. We will

be your authority."

Brennan was appointed

deputy commissioner of public works by Chicago mayor

Harrison in 1902 after serving as an alderman for

three years. He resigned in 1904 to pursue business

interests. He was married to Minnie Brennan and they

had four daughters.

|