|

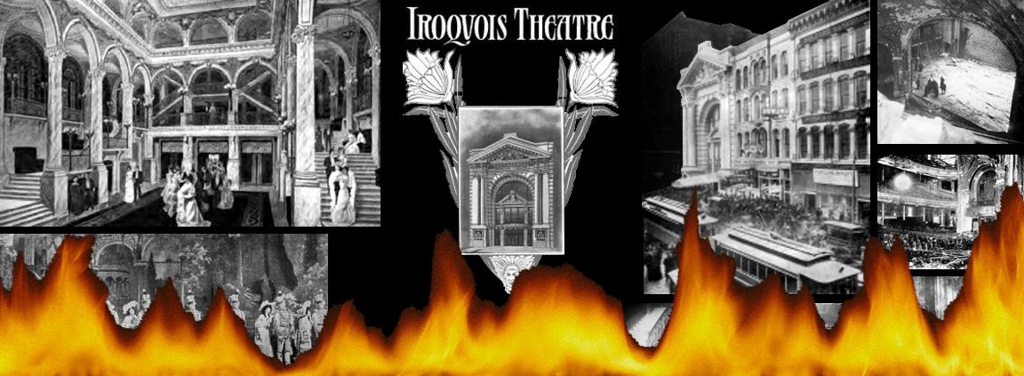

The smoke had barely cleared at the Iroquois when husband and father, Arthur E. Hull became an

outspoken crusader for justice, co-founding the

Iroquois

Memorial Association and pressing for conviction of those responsible. (More

about Arthur below.)

Dwight and Donald were the sons of Arthur's older

brother, the late John Frederick Hull (1866-1900) of Topeka, Kansas. They had been adopted just three

weeks before the fire, their mother, Della Mae Stout

Hull, having died the previous March.

Marion Hull was survived by her parents, Howard and

Phoebe Morey Kelsey, and her two sisters, Carrie

Kelsey Simmons and Helen Kelsey Pond, all of New

York.

Arthur Hull learned of the Iroquois fire around 5:00

pm that afternoon. His search for his wife and

children started at the temporary medical center set

up at J. R. Thompson's restaurant next to the

theater and lasted until around midnight when most

morgues closed their doors on the 30th so that

bodies, possessions, and paperwork could be

organized.

|

|

The next morning, Hull contacted his pastor,

Methodist Episcopal minister James Henry MacDonald (1865–1938),† who organized a large

search party, reportedly with fifty people, to

revisit the seventeen morgues and hospitals housing

Iroquois victims.

Marion and Dwight's bodies were found on Wednesday

among 278 victims at Jordan's funeral home and Helen

and Donald's among 66 at Gavin's funeral home two

days later. Mary Forbes' body was found and

identified on January 4th.

A funeral for the Hull family was held at Boydston Brother's funeral home on 42nd Place and Cottage Grove Ave, the service conducted by Reverend MacDonald). A poem found

in Marion's desk was read during the service. The

caskets were then transported to the 39th street

railway depot and shipped via Michigan Central

Railway to Troy, NY, for burial in the East

Greenbush Cemetery in East Greenbush, New York.

All three Hull children had attended the Oakland

school. A teacher at the school,

Millie

Crocker, was also an Iroquois Theater fire victim.

|

|

Arthur E. Hulll (1867–1944)

Became a prominent part of the post-fire story and went on to lead an interesting life.

In the first week after the Iroquois fire, Hull

filed a manslaughter suit against

Iroquois owners Will J. Davis and Harry Powers, along

with building commissioner Williams, and co-founded the

Iroquois Memorial Association.

Through his attorney,

Thomas D. Knight, he dropped the manslaughter suit a week after it was

drawn, announcing they were satisfied the coroner's

inquest and grand jury& processes

would properly prosecute the offenders. That

satisfaction lasted two weeks, ending when the

coroner jury's findings about Chicago's

democrat mayor were in essence overturned with a writ of habeas corpus,

and the prosecutor and judge publicly opined that

charges against the mayor were likely insufficient

to prosecute.

By then, Hull had bonded with Chicago's Republican

newspaper, the Inter Ocean wanted

the mayor's head on a pike, and Hull wanted the

deep-pocketed Iroquois co-owners/Mr.

Bluebeard producers, Klaw & Erlanger, to pay big. With the fanning

his fury, Hull launched a campaign of condemnation,

asserting conflict of interest with two of the grand

jurors —

Philip Sharkey because

he had contracts with the city and

Ernst Heldmaier because as a subcontractor of Fuller Construction his

company had laid stonework in front of the Iroquois.

When the prosecutor and other attorneys made clear

there was insufficient cause to remove Sharkey and

Heldmaier from the grand jury, and the other jurors

issued a statement of confidence in Sharkey and

Heldmaier, Hull began to insist there'd been a gas

explosion during the Iroquois fire as a result of

flammable chemicals brought to the fire by the Mr.

Bluebeard company. Hull began to seem desperate.

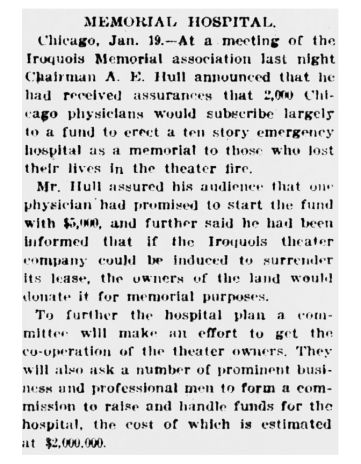

On Jan 18, 1904, he claimed that 2,000 physicians

would donate money for a large hospital and that if

the Iroquois corporation agreed to end its lease to

the property, the owners would agree to then sell it

to the Iroquois Memorial Association for the purpose

of erecting a $2 million hospital. It was the day

before the association's officers were to be

elected. If he hoped a relationship with the

landowners would win the presidency for him, he was

mistaken. The 2,000 physicians disappeared along

with his control of the association.

On Jan 18, 1904, he claimed that 2,000 physicians

would donate money for a large hospital and that if

the Iroquois corporation agreed to end its lease to

the property, the owners would agree to then sell it

to the Iroquois Memorial Association for the purpose

of erecting a $2 million hospital. It was the day

before the association's officers were to be

elected. If he hoped a relationship with the

landowners would win the presidency for him, he was

mistaken. The 2,000 physicians disappeared along

with his control of the association.

Hull persuaded Andrew W. Jefferis

Charles M. Bickford, and

John L. McKenna to join him in hiring investigators to collect evidence

and talked of hiring an attorney to sift through it

and submit it to the grand jury.

Instead of waiting for that evidence, or maybe

because it wasn't forthcoming, or perhaps because

Jefferis, Bickford, and McKenna weren't impressed

with what was found, Hull became convinced there was

a conspiracy. He produced a flyer claiming,

"powerful influences are at work to prevent the

punishment of those responsible." At the same time, hammered

incessantly about Chicago's evil mayor and crooked

grand jury proceeding, possibly giving Hull the

sense that he had strong supporters when in truth,

the comparative silence about Hull's accusations

from the city's leading newspaper, the Chicago

Tribune, should have been telling. Hull announced he was

giving up his business activities to focus full time

on punishing those who caused the Iroquois fire.

The clamor went on until February 13, 1904, when the

grand jury demanded a kind of courtroom showdown.

They subpoenaed Hull to explain and substantiate his

accusations. After a closed-door meeting between

Hull and assistant state attorney

Barnes,

Hull was questioned by the grand jurors. At last,

Hull admitted he could produce no evidence

demonstrating that Sharkey or Heldmaier's were

biased, no evidence of an explosion, no evidence of

a conspiracy. It was over.

|

|

The grand jury's vote to indict Davis, Noonan,

Cummings, Williams, and Laughlin/Loughlin was

announced on February 20, 1904, followed by a

detailed report three days later explaining their

verdict.

Hull resigned from his position as first vice

president of the Iroquois Memorial Association on

February 24, announcing that he was headed first to

Kansas City, then to California, and might not

return to Chicago.

Perhaps hoping to find other victims willing to mix

politics and grief, the Inter Ocean ran

a story seemingly geared to drive a wedge between

members of the Iroquois Memorial Association. IMA

didn't bite, announcing it would continue with its

primary goals: erecting a memorial to Iroquois fire

victims and raising monies to assist destitute

families of victims.

Did Hull have a hand but played it poorly? Was he

bluffing? Was he manipulated by the Inter Ocean?

I doubt the answers will ever be known for sure.

Hull did return to Chicago, or remained there, for

at least eleven months, at which time he married

Emma Louise Firmenich (1862–1941), daughter of

wealthy starch producer, Dr. Joseph Firmenich, who

had died a couple of months before the Iroquois

Theater fire. Firmenich was a homeopath who made his

fortune in Buffalo, NY and relocated his family to

Chicago later in his life.

Though Hull had described himself as an attorney while

living in Chicago, operating as the president of the

J.P. Wood Claim and Adjustment Company (business

unknown, sounds like insurance), I found no evidence

of his attending law school, and he hired an

attorney to assist in filing a warrant relative to

the Iroquois Theater. I did, however, come across an

1899 blurb in his hometown Kansas City newspaper

about his being in town for a visit, boasting of his

half-million-dollar worth earned in real estate in

Denver and Chicago. No mention there of his being a

lawyer.

Hull was a man of great energy and ambition. Some highlights of his life:

1888 — believed to have been released from a 5-yr term in U.S. Navy

1906 — motored in Yosemite with 2nd wife and

friends

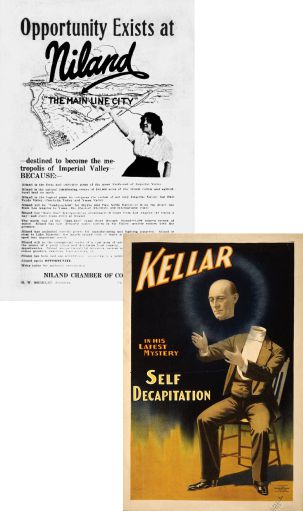

1910 — pallbearer with his partner W. H. Cline for Eva Kellar, widow and stage assistant of

legendary magician, Harry Kellar

1911 — sold oil land in Oxnard, CA, losing partner Cline and in San Francisco, again

claiming to be an attorney

1912 sold land in Victor Valley, California that

would eventually become Victorville, where he

became the first president of the chamber of

commerce

1913 negotiated the $2 million purchase of

47,000 acres of land in Imperial Valley,

California

1914 named town of Niland, California in

Imperial County.

1920 living in Los Angeles, working as a

realtor

1944 — His obituary claimed he was an

"archeologist of note" and had made "several

important discoveries in the Valley of the

Nile." I was able to verify most claims in his

obituary, but neither of those. Might be that

was as much a stretch as the claim that he was

an attorney. In his 1920's real estate

advertising, Hull demonstrates a love for

superlatives. Biggest, best, largest, most,

greatest, etc. He wouldn't have been the first

high-powered salesman with a penchant for

gilding the lily.

Notably, his obituary

omitted mention of Marion, Helen, Dwight, and

Donald.

|