|

Victoria Dray's name appeared

in a newspaper list of Iroquois Theater victims the

day after the fire and also in the Everett Marshall

book about the fire. Her name was not included in

the coroner's inquest list, however, nor in

subsequent newspaper coverage and no death

certificate was issued for her.

For other individuals with a conflicting status,

the trail has led sometimes to an Iroquois victim

and other times not, so I set about looking for

signs that Victoria Dray was alive after December

30, 1903.

Fruits of the hunt were so bountiful that it's hard

to decide what to pass along. She had no children,

so there may not be another living person who is

interested in Victoria, but it would be a shame not

to recognize such a character.

Victoria may or may not have attended Mr.

Bluebeard at the Iroquois but definitely did not

die there and was probably not injured. That last

conclusion is based partly on a sense that if

Victoria Dray had lost so much as an eyelash at the

Iroquois, she would have led the fight to prosecute

the theater syndicate.

She was thought to be dead, however, for long enough

that an Iroquois Theater victim's body was

misidentified as Victoria's.

Mary Frazier's body was twice misidentified, once by

a relative of Victoria Dray's and another time by a

relative of

Mary Forbes.

Victoria Clara Guillott (1873–1937) was born in

Vermont to Canadian natives Hubert and Sophia

Guilott. The family moved west and by 1882 lived in

Minneapolis. Victoria remained in the Midwest as an

adult while her parents and some of her five

siblings resettled in Montana.

In 1899 Victoria married her first husband,

commercial realtor, and mortgage holder, Homer Ira

Dray (1872–1901), of Chicago. Homer may have gotten

his start in real estate by working for his uncle,

Walter S. Dray, a Chicago realtor, from the

mid-1880s until his death in 1894. Walter's estate,

adjusted for inflation, would today amount to nearly

$5 million. I was not able to learn how Homer died,

but I am curious, so drop

me a line if you have information about his

death.

No children resulted from Homer and Victoria's

marriage, probably because he died before their

third anniversary, and she did not remarry until she

was forty-five. Victoria's inheritance was

sufficient to let her travel, do a bit of financial

speculation, and maintain homes in several cities,

or so she claimed, so she may have been too busy.

Her 1905 hiring of fifteen-year-old Minnie

Pfannenschmidt may have been born of maternal

yearnings (see below).

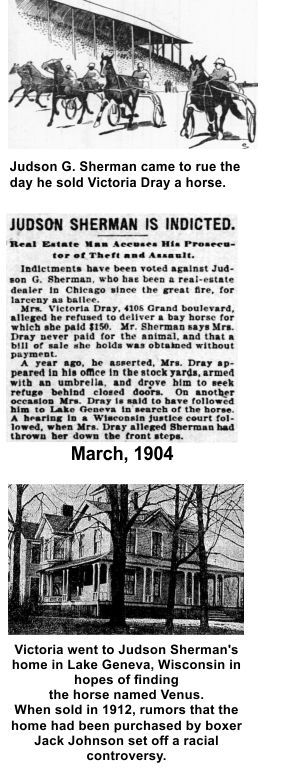

Race horse named Venus

In February, 1903, nine months before the Iroquois Theater opened, Victoria was

making her own drama in Chicago newspapers. She maintained she'd purchased a

horse named Venus for $150 from Judson G. Sherman (1844–1913) who then refused

to produce the horse. A one-time banker, Sherman was treasurer of the National

Horse Sale Company in Chicago, specializing in the sale of harness racing

horses. Judson maintained that Victoria never paid for the horse, that the

receipt she presented was inaccurate because the ownership transfer of Venus

depended upon a real estate transaction that was not completed.

Victoria was having none of it.

She first staged a six-hour sit-in at his office,

refusing to leave and threatening Sherman with her umbrella. While ensconced,

Victoria answered a few of his phone calls, ordered in lunch and made herself an

annoyance until he physically ejected her. The manner of the ejection would

become one of Victoria's several suits against Sherman. The sit-in came to the

attention of the newspaper and the resulting story read like a Lucy Ricardo and

Mr. Moony skit. In 1903 it probably made Victoria a subject for derision.

Undeterred, Victoria spent the next year pursuing Sherman. She went looking for

the horse at his home in Lake Geneva. When she found no Venus she pled her case

to Wisconsin courts and succeeded in seeing Sherman indicted for larceny in

March, 1904. Meanwhile, Victoria brought a $10,000 suit against Sherman for

throwing her down the stairs when he ejected her from his offices in 1903.

Nothing was reported about the conclusion of either case but Sherman's

horse-selling career was not interrupted, so he was not imprisoned, indicating

there was a settlement.

Parental child abuse in 1905

In 1905, Victoria's name again appeared in the newspaper, this time as an accidental

participant in a child abuse case.

Fifty-four-year-old widower, William Pfannenschmidt (1854–1946), who had

immigrated to America from Inbenck, Germany in 1875, earned his living selling

oil door to door. His second wife died in 1903, soon after their wedding,

leaving him with six children aged four to fourteen.

Four of the Pfannenschmidt children remained at home in 1905 when William

Pfannenschmidt went to Nebraska to find a homestead. He left his

fifteen-year-old daughter, Helen, nicknamed "Minnie," in charge of the

household, including the garden and her three younger siblings, aged nine to

twelve.

Victoria Dray lived near Minnie but not close enough to easily explain how they came to

know one another. However they became acquainted, the result was that Victoria

hired Minnie to work for her — in an unknown capacity but presumably as a

domestic — in exchange for clothing and an unreported amount of money. Such

arrangements were common in the early 1900s when children were sometimes viewed

as laborers.

When William returned from Nebraska and learned Minnie had not done as

instructed, he beat her with his fists, whipped her with a belt, and kicked her.

Minnie fled and went to the Friends of the Homeless, who reported the abuse to

the police. William was arrested and his case was heard by judge Healy.

"My father pounded me with his fists and kicked me," she said to Judge Healy. "I

worked as hard as I could and tried to keep the house clean for him." Pfannenschmidt

was fined, Minnie Pfannenschmidt remained with Friends of the

Homeless, her eleven-year-old sister Annie Helen Pfannenschmidt went to live

with an older married sister, Emma.

The two boys, nine-year-old Charles and twelve-year-old Fritz, remained with

their father. William remarried two years later to his third wife,

forty-eight-year-old widow, Mary Collins, becoming stepfather to Mary's

fifteen-year-old daughter, Susie Collins.

The story of the Pfannenschmidts doesn't end just yet. Three weeks after the wedding, Mary

died under circumstances that a neighbor, family priest, and her daughter Susie

found suspicious. They thought William had poisoned Mary for her small nest egg

and had possibly done the same to his prior wife.

Police and the coroner's office investigated and found nothing to suggest Mary

did not die of natural causes. The following year William married a fourth time,

but that wife too would be gone when he died in 1946 at age ninety-two.

Nothing was reported about what happened to Susie Collins. Hopefully, the courts

did not force her to return to the home of a man with a history of violence whom

she'd accused of murder.

And what became of Minnie? By 1940 she was widowed and worked as a cook —

living with the father who had beaten her thirty-five years before.

Victoria tries on a millinery enterprise

Just a period-appropriate illustration of a woman wearing a hat,

not Minnie or Victoria.

In 1907 Victoria incorporated the Victoire millinery

company in New York with V. Mayne Turner, Alexander S. Bacon, and herself as

directors. A year later, it was reorganized with

herself as president, Mabel Dickinson as secretary,

and Alexander S. Bacon as a director.

|

|

Initial capitalization was $2,000. Other than incorporation filings, I found no evidence

of business activity. Alexander Samuel Bacon was an author, and V. Mayne Turner

owned the copyright on one of Bacon's books. In 1916 the pair formed a

partnership in a printing firm.

Victoria back in court, wins suit against Lithuanian

In 1908 Victoria brought suit against a Chicago tailor

for refusing to reduce his bill for dresses she maintained fit poorly. Reported

as George Gansky, the tailor may have been twenty-nine-year-old Joe Ghenski, who

lived on Ellen St. with twelve other Lithuanian and Russian tailors and

seamstresses.

Victoria likely cited expert knowledge as her father and brother were tailors.

Municipal Civil court judge of the First District, Edwin K. Walker (186_–1953),

had Victoria don two of the four dresses she purchased and ruled that one was an

inch too long and the other an inch too loose at the waist. Walker ordered the

tailor to turn over all four dresses and reduce his bill by $12 (another paper

reported $22). Victoria gloated to the press.

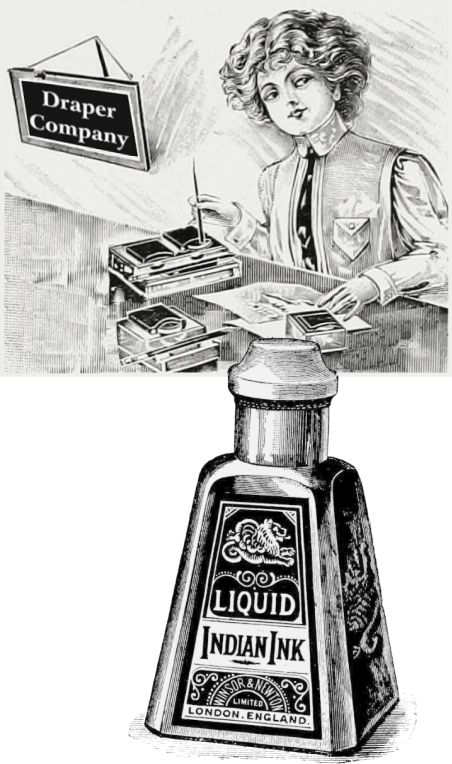

Stakeouts, wanted posters, burglary and lies bring Victoria a third win in the courts.

In 1910 Victoria spent much

of the year in Detroit courts pursuing officers of

the Draper Company Ltd. She wanted compensation for

the job she claimed they'd offered and return of her

$1,000 investment.

Victoria went after three of its founders: Arthur

Wellington Draper, John D. Kuppenheimer (known as

the Prince of Bu) of the Oriental Silk

Company of Montreal, and John's brother, Jacob D.

Kuppenheimer.

The Draper Company had been incorporated in 1909 to

manufacture indelible ink and carbon paper, with a

head office in Detroit. Victoria contributed $1,000

to their original $100,000 in capital. She asserted

that Kuppenheimer also promised her a job as a

traveling sales representative with a $40 weekly

salary.

When the company and job failed to materialize, and

Kuppenheimer denied having made the job offer,

Victoria hired an attorney — and went to work

herself on a variety of schemes to bring pressure on

the plaintiffs:

-

When Draper evaded an arrest warrant, Victoria had fliers printed that

pictured the principals in the company and offered $200 for information about their

whereabouts. Newspaper reports did not state how many fliers were printed or how Victoria managed

the distribution, but Draper's wife came across one of the fliers while traveling in England.

-

When Victoria learned that Draper was back in Detroit and planned to

escape again, she hired a taxi and did stakeouts

at various train depots until she spotted him.

She summoned a policeman, and Draper was arrested.

-

A dramatic courtroom moment came when Victoria submitted copies of

letters that overnight had disappeared from

Draper's office. Newspapers did not report

whether Victoria pulled off the document heist

by herself or hired a burglar.

In court records, she reported corset modeling as her occupation, for

the American Lady Corset Company. I checked decades

of ALC advertisements, but all incorporated stylized

illustrations of young ingénues, and I found nothing

to corroborate Victoria's involvement with the

company. At thirty-seven, she probably no longer had

a look the company favored, but the company did have

a line of models for fuller figures.

In any case, for Victoria,

there were always alternate facts. When it became important in

prosecuting the case against Draper for her to be a

Michigan resident, Victoria testified that she had

always had a residence in Detroit. She must have

meant except for from 1899 to at least 1907 when she

lived in Chicago. Had someone checked, they would

have learned, that the only Dray in Detroit

City directories 1907-1915 was a single man.

Victoria Dray's name did not appear until 1916 (but

I could not find her in the 1910 US Census, so she

may have been in Detroit, but the directories missed

her — for a decade). At other times she claimed to

have residences in Chicago, Manhattan, and Paris. I

don't know about Paris ,but in Chicago and

Manhattan, her residence consisted of a room in a

boarding house.

Kuppenheimer hit back with numerous countersuits,

but in the end, there was a settlement returning

Victoria's $1,000 investment plus $1,000 for her

trouble.

Victoria moves to Michigan, becomes Victoria Clara Guillott Dray

Lebert

Victoria lived in Michigan the last two decades of

her life, operating the Antler's Stag Hotel and cafe

and marrying in 1918 and again in 1925.

Second husband

In 1918 she married Canadian,

Adelard Lebert (1883–___), age thirty-five, and the

pair settled in Port Huron, Michigan. Four years

into the marriage, Adelaid disappeared after he and

Victoria argued (perhaps about her having claimed

she was only thirty-five at the time of their

marriage instead of her actual forty five), and did

not return home. Victoria filed for desertion a few

months later but continued making payments for the

next three years on his two life insurance policies

for coverage totaling over $8,000. While watching, I

suspect, for news of a death that met her purposes,

i.e., one involving an unrecognizable and

unidentified male corpse within a short distance of

Port Huron.

Having been briefly thought an Iroquois

theater victim herself, Victoria would have followed

Iroquois news closely and known about the various

miss identifications of badly burned bodies. Thus a

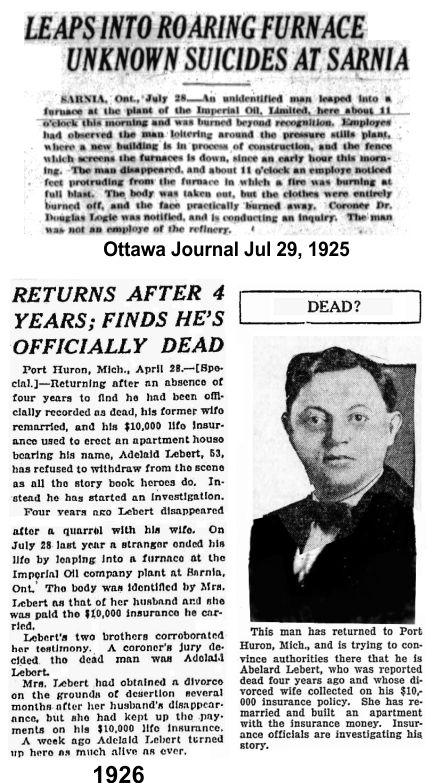

story in July 1925 of a horrific suicide may have

been just what she was looking for. Across the St.

Clair River in Sarnia, Ontario, an unidentified man

jumped into a flaming furnace at Imperial Oil

Limited and was burned beyond recognition with only

a portion of the face remaining.

He wasn't dead

Victoria came forward to identify the body as her

missing husband, Adelard Lebert. Corroborating

identifications from Adelaid's two brothers

convinced the coroner, Dr. Douglas Logie, who issued

the death certificate for Adelard Lebert. The Lebert

brothers paid for funeral services, and Victoria got

the death certificate she needed to collect the life

insurance payout. She used the $8,000 to build an

apartment building, even naming the building Adelard

Apartments.

The following year Adelard Lebert turned up very

much alive. He had been traveling in California,

Washington, and Florida for the past four years.

Upon returning to the area, presumably to visit

family in Ontario, he learned of his supposed death

and thought his brothers should be reimbursed for

the funeral expenses of the stranger they'd buried.

The insurance company tried to force Victoria to

return the money, but she denied that the man who

claimed to be Lebert was her husband. Victoria

challenged the insurance company and assistant

prosecutor in Port Huron, Jesse Wolcott, to prove

that the man who claimed to be Adelard was actually

her husband — accurately calculating that they would

not, or could not, do so. Adelard's parents were

deceased. There were siblings who could have

identified him, but the situation called for people

who could connect Adelard to Victoria, and it's

possible they all lived in Canada. Bringing them

across the border to testify may have been

problematic.

For his part, Adelard laid no claim to the insurance

money. Presumably, he had not paid the premiums on

the policies prior to his disappearance in 1922.

Whatever the considerations, the case was dropped.

Victoria kept her apartment house.

In 1925 at age fifty-two, Victoria married a third

time to a retired contractor in Port Huron, an

eighty-year-old widower named William Manley

(1845–1927). It was reported that Manley had been a

friend of Adelard Lebert. I failed to find online

information about William Manley's will.

Victoria buried in an unmarked grave

Victoria died at age sixty-two in 1937 of ovarian

cancer. She was buried in an unmarked grave at the

Lakeside Cemetery in Port Huron, Michigan, alongside

her third husband, William Manley, and his first

wife. (Semper fi, Mr. Lindsay.)

|