|

"Not my job."

The #1 cause of 600+ deaths at the

Iroquois Theater fire in 1903 Chicago was that dozens of people gambled that someone else would address the problem. William

Sallers, Iroquois fireman, was one of those. In his defense, he did discuss the theater's woeful fire response capacity with a

fire department captain, who in turn discussed it with a battalion chief, who took his seat at the roulette table by failing to take it to the Chief.

There were no legal protections for whistle

blowers in 1903 and large advertising expenditures gave the theater Syndicate power with newspapers but another man than Sallers might have

fought harder to bring the situation to the attention of authorities. The sad truth is that Sallers or his immediate superiors in the

fire department could have marched into Chief Musham's office, together or separately and said, "There's something you need to know about the new

Iroquois Theater." There is no way to prove it but my gut feeling is that curmudgeon though he was, Musham would have

listened and acted. He had the ear of Mayor Harrison who a few weeks before had tasked the city council with revising the

city's fire ordinance so presumably would have been a receptive ear. Instead, all involved put the lives of nearly two thousand people on a bet that

fire would not get started at the Iroquois before the theater was properly equipped.

Fireman Sallers: facts and speculations

Chicago regulations in 1903 required that a fireman, approved by the fire

marshal, be present during theater performances. At the Iroquois, the house fireman, recommended by

assistant fire marshal

John Campion, was a former Chicago firefighter named William C.

Sallers (c.1864–1917).* (Another applicant for the

position had been the

son of fire marshal Musham,

who withdrew his application to take a job with the

World's Fair in St. Louis.)

Sallers would describe himself as a retired fireman for

the rest of his life, indicating it was something he took pride in — despite the damage to his

name and reputation for fifty days in newspapers throughout the country.

The son of German immigrant, Henry Sallers, William

was a Chicago fireman until at least 1900, though in the 1900 U.S. Census he reported not having

worked for the prior twelve months. His job as

the house fireman at McVicker's Theater was

between 1900 and 1903. He married Augusta "Gussie" Rabe (1880–1938) a month

before the Iroquois Theater fire but the marriage failed by 1907 and she remarried. He continued

to report "fireman" as his occupation until 1906

and "retired fireman" from at least 1910 until his death in 1917.

Based on the minimal information I've learned about William, I suspect he may have been an introvert.

Personable enough to win a job

recommendation from assistant chief John Campion, but not valued enough as a fire fighter for

Campion to want to keep him in a Chicago

firehouse. The department's lack of concern about the Iroquois makes clear that the fireman's

job there was not deemed highly important and

Sallers was only forty-five when he went to work at the Iroquois. Not yet old enough or with

the department long enough to be rewarded with a

semi-retirement position. Instinct tells me Campion would not have furloughed a good

firefighter to a watchman's job and that something was amiss with Sallers firefighting,

health or interpersonal skills. The Iroquois assignment was a face-saving

jettisoning.

Sallers got caught in a situation beyond his understanding. Though he didn't

try as hard as he could have to alert authorities about the dangers at the Iroquois,

at least he did try. He stuck his neck out, albeit carefully. That's more

than can be said of anyone else who knew the Iroquois was a fire trap and was in a position

to share their knowledge with someone who could do something about it.

Perhaps the Grand Jury recognized it because they exonerated Sallers on February 18, 1904.

|

|

Theater fireman's job

According to city ordinance, Saller's job was to

verify the installation and operability of fire

apparatus at the theater. There was no system in

place, however, with which he could force Iroquois

management — the folks who signed his paycheck — to

purchase said equipment, or contract for its

installation. According to John Campion, Sallers had

been fired from his former position as fireman at

McVicker's Theaer

for having been overzealous. No surprise then that he was cautious about what he

said to Iroquois management as to the inadequacy of

six tubes of Kilfyre powder as the sole fire-fighting equipment in the theater,

or the lack of water plumbed to standpipes, or the nonfunctioning roof vents over

the stage, or the absence of fire axes, fire hooks or a fire alarm.

Grand Canyon size communication gap

Theoretically, Sallers reported to fire chief

Bill Musham

but both Musham and Sallers viewed it that Sallers

was an employee of Iroquois Theater management and only accountable to them.

Not only did Sallers never send a report about the Iroquois to Musham, or meet with

him; reportedly it did not occur to man that such direct communication was necessary.

Musham thought it was up to the building department

to arm-wrestle theater owners; Sallers didn't know

whose job it was, but he wasn't going to become

unemployed again for making a todo about a theater's poor fire preparedness. In a

letter to the Grand Jury, Sallers described having

called McVickers Theater's inadequate fire prevention

equipment to the attention of Musham and of Musham

having told him to take it up with McVicker's

management.†

As an armchair quarterback, the gap in the chain of

command seems Grand Canyon size, but in 1903 it took

the Iroquois fire for Chicago to see it.

Perfect Storm in the making

Sallers wasn't altogether silent about the Iroquois

situation. He expressed his concerns to the captain

at the firehouse on Dearborn street, the one closest

to the Iroquois,

Captain Jennings, who got the message, loud and clear. Jennings later

testified that after touring the Iroquois he told

Sallers, "If this thing starts going, they will

lynch you."

To his credit,

Jennings did not bury the information. The man with

the disaster shovel was his boss, battalion chief,

John J. Hannan.

When Jennings took the matter up the chain, Hannan,

according to his own later remorseful admission, did

nothing, even though his own inspection of the

Iroquois corroborated the opinion of Sallers and

Jennings as to the theater's inadequate fire protection. Like Musham, Hannan thought it was the

building department's job to close firetraps.

In cinema or novels, a man with Jennings or Hannan's

knowledge might have thundered into Chief Musham's

office or become a

whistle blower and gone to the police or media. In

real life, we should shower whistle blowers

with accolades, even when we disagree with their

revelations, because the Iroquois Theater fire is

what you get if they're are silenced.

|

|

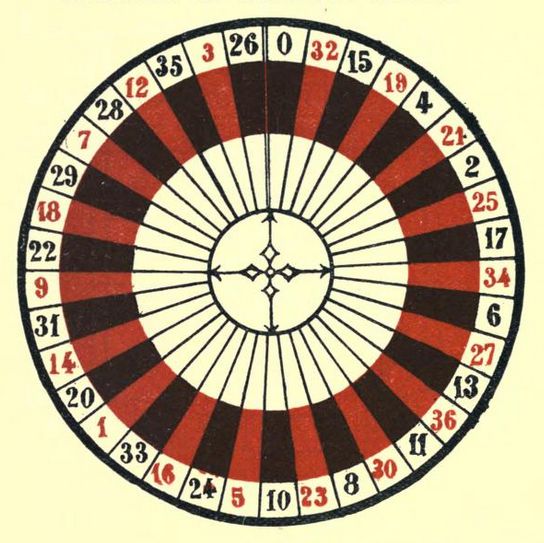

The big gamble

For five weeks, several Chicagoans who were in a

position to have prevented the Iroquois disaster instead spun

a roulette wheel, all of them with their souls anted

on the hope that a fire would not break out at the

Iroquois

before it was fixed, by someone. Sallers

patrolled the theater (paying particular attention

to the basement where he'd once found evidence of

stage workers smoking cigars), while waiting for

Iroquois management to get around to having a water

tank installed on the roof top, making sure the standpipes were

plumbed, and fixing ceiling vents above the stage. The building

department waited for the city council to act on

George Williams' report that Chicago theaters were

firetraps. The city council pushed the report to the bottom of

their task list, knowing any legislative action would bring a

hailstorm of vote-threatening controversy. Thomas Noonan, Iroquois

business manager, waited for his employer to get

around to installing an alarm. Chicago firefighters, Jenning and

Hannan, waited for all of the above. The fire department waited for a resolution between insurance underwriters

and Mayor Harrison that would determine whether Musham would remain

on the job as fire chief.

before it was fixed, by someone. Sallers

patrolled the theater (paying particular attention

to the basement where he'd once found evidence of

stage workers smoking cigars), while waiting for

Iroquois management to get around to having a water

tank installed on the roof top, making sure the standpipes were

plumbed, and fixing ceiling vents above the stage. The building

department waited for the city council to act on

George Williams' report that Chicago theaters were

firetraps. The city council pushed the report to the bottom of

their task list, knowing any legislative action would bring a

hailstorm of vote-threatening controversy. Thomas Noonan, Iroquois

business manager, waited for his employer to get

around to installing an alarm. Chicago firefighters, Jenning and

Hannan, waited for all of the above. The fire department waited for a resolution between insurance underwriters

and Mayor Harrison that would determine whether Musham would remain

on the job as fire chief.

They let it ride until December 30, 1903

The roulette wheel stopped spinning around 3:30 pm

December 30, 1903. While trying to fling Kilfyre

(baking soda in a tube) at a fire that in minutes

raced a hundred feet over his head, Sallers

repeatedly shouted, "pull the box!" (So either his

building patrols had not revealed to him that the

Iroquois was not equipped with an alarm or he

wanted someone

to go outside and find an alarm on the street. How could he not have

known there wasn't a fire alarm at the theater?)

Twenty minutes later, all the players — Musham, Campion, Jennings, Hannan, Sallers, Davis, Noonan, the city

council, and Mayor Harrison — saw the horrific results of their gamble.

Then began the next phase of humans behaving badly

as elected officials, civil servants, theater owners and employees looked for someone to blame.

|