|

Iroquois Theater orchestra probably included twenty-six muscians

I've found no lists of members of the Iroquois

Theater orchestra and varying period references up to forty members. An interview with

director Dilley reported twenty-six; a newspaper

report in the Richmond, Indiana newspaper where

lived the parents of cello player Eddo Kline,

described their relief at learning their son was

among the survivors in the thirty-three member

orchestra. Philip Carli,▼1 (to whom I am much

indebted for providing information about theater

orchestras of the period), feels twenty-six was the number that would have been in keeping with theater orchestra compositions of the time.

Those identified thus far are listed at right in the

green panel. (I'll update the list as more information

is found. This story will be "in progress" for some

time.) So far I've identified the names of nine men and one woman.

Play on

Comedian Eddie Foy and

both orchestra directors at the Iroquois Theater

believed that music would calm the audience. Since

multiple audience survivors described being unable

to hear Foy from the stage, urging calm, it is

likely they were also unable to hear the orchestra

playing. Nearby screams functioned as a sound

barrier. Nonetheless, a half dozen musicians kept

playing until soon after the fireball shot into the

auditorium.

According to testimony at the coroner's trial, Eddie

Foy urged the orchestra to play an overture, and

director Herbert Dillea led the group in playing

the Sleeping Beauty and the Beast Overture. Sleeping Beauty was

another Drury Lane Theater production that Klaw and

Erlanger had imported and for which

Frederick Solomon had composed much of the music, playing in August 1902

at the Illinois Theater in Chicago, also managed by

Will J. Davis, probably by some of the same musicians that were

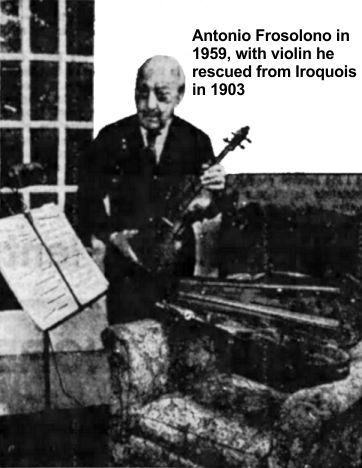

performing Mr. Bluebeard at the Iroquois. Second director and violinist Antonio Frosolono also described urging the musicians to keep playing.

On January 7, 1904 Frosolono testified before the

grand jury about his experience at the Iroquois

Theater. He described the fire curtain lowering,

sticking, and bulging just before the fireball

hurled into the auditorium. He also told of a fire

hose beneath the stage in a restroom. (Later witnesses would

testify that water had not been plumbed to the stage

fire hoses.)

Frosolono and a half dozen other musicians,

including Dillea and Brown, continued performing

until the bass and cello caught fire. Brown

testified that they had no more evacuated than the

woodwork in the pit caught fire. Eddie Foy was

quoted as saying that by the time the last orchestra

member, Herbert Dillea, left the orchestra pit, the

ground floor of the auditorium was half emptied.

Foy and Brown's remarks reveal that though there

were few fatalities among audience members seated on

the ground floor, the risk to musicians was greater

than I appreciated initially. The orchestra pit was in

flames as the last of the audience on the ground

floor moved into the lobby, which means musicians

who stayed to perform had to flee quickly.

Under ordinary circumstances musicians were expected to leave the orchestra pit via an 18-inch wide exit beneath and in front of

the stage that led to a stairwell down to an east-west basement hallway lined by dressing rooms, costume

rooms, and, at the south end, washrooms and smoking

rooms used by theater patrons. Musician Arthur C.

Brown described the opening as narrow and awkwardly

configured, requiring the musicians to "twist and

wiggle" to pass through. At the end of the hallway was another stairwell that led up to a exit out onto Dearborn St.

(door #5). When that passage became filled with smoke some orchestra members such as

Anthony Frosolono, escaped through a bathroom window.

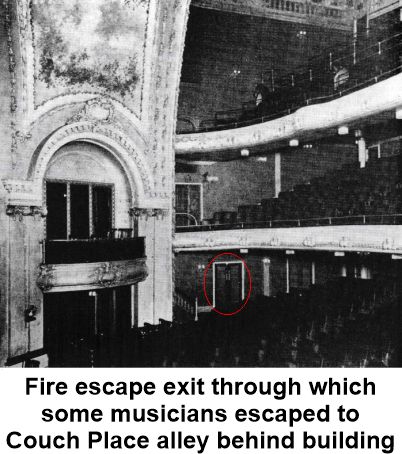

Others made their way to a spiral stairwell on the

north side of the theater that ran from the basement all the way up to box seats on the second floor. At the first

floor was a set of stairs that branched out to the auditorium floor (see accompanying photo)

and a fire escape exit on Couch Place alley (door #2).

The orchestra pit exit was compromised due to another Iroquois

planning error. The floor depth was originally seventy-eight inches, said to be in keeping with European standards at the time. At the dress rehearsal, it was decided that the music could not be heard sufficiently so a false wood floor was installed atop the concrete floor, raising the floor height. Still unsatisfactory, a second wood floor addition was installed. The measurements cited in

newspaper stories resulting from an interview with Arthur

Brown are conflicting, and the actual floor height in the

orchestra pit is not known but there's little wonder

some musicians were forced to leave their

instruments behind.

By the time the fire was out and bodies removed,

the basement and orchestra pit was

filled with water from the fire hoses, requiring

pumping the day after the fire.

The often published picture of a fire pumper in

Couch Place alley was likely taken the day after the

fire when the basement was being pumped.

|

|

|

Iroquois Theater orchestra members:

-

Herbert Dillea — 1st baton

-

Charles Bibel — trombone

-

Arthur Curry Brown — double bass

-

Carlos Arriolas — flute

-

Ernest M. Libonati — violin

-

Florence Louise Horne (1880–1956)▼2 — cornet

Studied with composer and cornet virtuoso,

Robert

Brown Hall, and performed as soloist with various groups,

including the Fadettes of Boston, Cecilia Musical Club, U.S. Ladies

Military Band, Tuxedo Ladies Band, George C. Wilson Repertory

Company, Ward & Vokes comedy team, Talma Ladies Band, Miss Reno

Mario's Orchestra, Hotel Rudolf in Atlantic City, Twelve Navajo

Girls, Navassar Band and the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in NYC. Florence was

performing in Kansas City, KS when she met bank clerk Edmund W.

Stilwell. When she returned to her home in Bangor, Maine to

continue teaching the cornet, he followed her. They married in

1910. Edmund went on to become chairman of the board of the

Commercial National Bank in Kansas city. Thereafter she confined her musical activity

to teaching, though she did perform at Fort Riley during world war I.

One of her two daughters, Winifred Stilwell Culp, would serve as a

lieutenant colonel in the Women's Army Corp during world war II.

-

Edwin A. "Eddo" Kline (1881–1941) — cello. One of five

children born to Quakers Isaac and Jenny Talbert Kline of Richmond,

Indiana. At Isaac's death Jenny moved to Chicago and lived

with Edwin and his wife, Louella, in Chicago. Edwin continued

to work as a musician into the 1930s, playing with the Chicago Civic

Orchestra. Ill health forced his retirement from performing in

1936 but he worked as in sales for a time. He and Louella had

one child, a daughter named Edwina.

-

Michael Ernest Libonati — cello

-

Antonio Frosolono — 1st violin, Iroquois music director and 2nd baton

- John H. Miller - 2nd violin (1872–1924). Known as Johnny, from Logansport, Indiana. He worked in

Chicago in the early 1900s, performing in theater orchestras and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. By 1922 he'd returned to

Logansport where he gave music lessons at the Frank H. Brown Music Store on Broadway.

- 16 unknown musicians:

2 first violins

3 second violins

2 violas

2 percussionists

2 clarinets

1 oboe

1 bassoon

2 French horns

1 cornet

A Chicago musician who died at the Iroquois Theater,

flutist Otto

Helms , is thought to have been in the audience that day

rather than in the orchestra. Had he been performing,

it is certain newspapers would have made much of it as they did of aerialist Nellie Reed.

Wikipedia offers

an interesting look at the instruments used in pit orchestras for

various musicals. Peter Pan of 1904, might provide

clues as to the instruments in Mr. Bluebeard.

|

|

|

Lyricists contributing to Mr. Bluebeard music

Vincent P. Bryan

(1877–1937) composer and lyricist

Edward "Eddie"

Gardinier / Gardiner (1861–1909) Slit his own

throat while depressed about poor responses to

his songwriting in 1909. Other

compositions included: "Schoolmates," "Oh, Mr.

Dingle, Don't be so Stingy," "Captain Baby

Bunting" and "Everybody Loves Me but the Girl I

Love." A newspaper obituary credited him

as the author of the familiar tune, "School

days, school days, dear old Golden Rule days,

readin and writin and rithmatic, taught to the

tune of a hickory stick..." but I found nothing

else connecting him to the song. Lived

with his sister, Laura Gardinier, a dressmaker,

in Brooklyn, NY.

John Cheever Goodwin

William Jerome

Jean Schwartz

Andrew B. Sterling

Matthew Woodward

|

|

Discrepancies and addendum

1.

Philip Carli is a musicologist, sound recording historian, film

scholar, film accompanist, pianist, conductor and

author.

† Some online biographies inaccurately cite

Florence's date of birth as 1890. Her marriage

license, census reports and obituary cite 1881 and

1880. Her grandson reports it was 1880. Stilwell was sometimes spelled as

Stillwell. Later in life, Florence went by her

middle name, Louise.

|