|

Enlarge to read John's description |

|

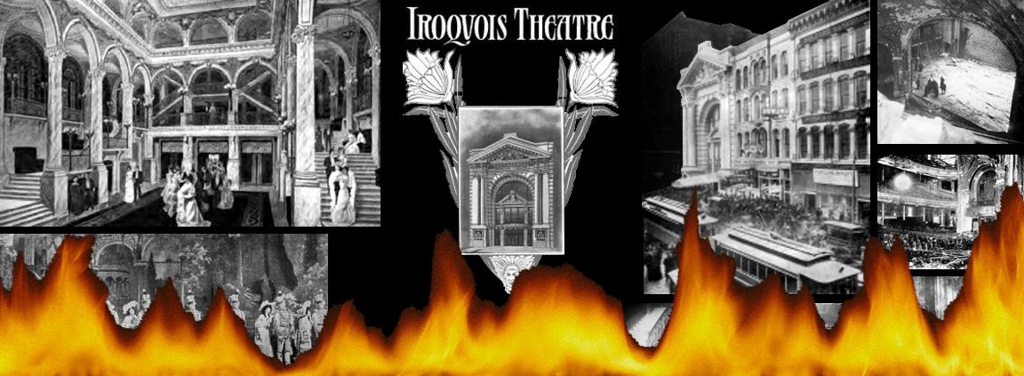

During a performance of Mr. Bluebeard at

Chicago's new Iroquois Theater on December 30, 1903, a stage fire spread to the auditorium. Within twenty minutes nearly

six hundred people died. Among the survivors was a party of four made up of a Welsh immigrant named John Griffith and

his three unidentified companions, another man and two women (one of whom was probably Emma Miller who would become Griffith's

wife four months later). The foursome had left the auditorium during the intermission prior to Act II and was a bit

late in returning to their seats at the front of the second-floor balcony. When they heard outcries of, "Fire!"

Griffith insisted they evacuate immediately

and they became members of a group of approximately one-hundred-seventy survivors from that balcony.

|

|

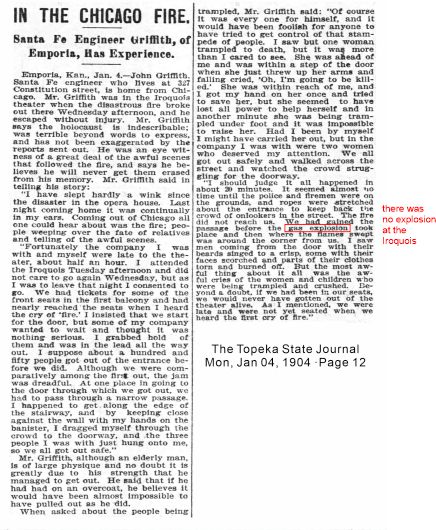

From Wales to Iowa to Kansas Welshman John Griffith (1861–1926▼2) was an engineer on the

Santa Fe Railroad ,living in Emporia, Kansas,

widowed for eight years and living with five of his eight children. Though he was recorded as being married in the 1900 U.S.

Census, his wife Mary Owens, also a native of Wales, had died of breast cancer in 1895. They had married in 1874, lived in

Iowa for a time, then in 1893 settled in Emporia, Kansas.

|

|

In the years after the fire Four months after the Iroquois Theater fire he married a widow from Canada, dressmaker Emma Elizabeth Miller (1860–1937),▼4 a woman who lived in Chicago in 1903 but had lived in Emporia during her childhood and first marriage., at least until 1900. I looked at Emma's many sisters, and John's children hoping to guess the identities of the other couple in the Iroquois theater party. One of her sisters could have been visiting the U.S., but I didn't see any that relocated to Chicago. Another possibility is that it was one of the couples mentioned in their nuptials (Swanstrom, Romaine, Dyne, Smith, Leonard or Pinch); if so nothing was published linking their names to the Iroquois disaster.

|

|

1. John was not alone in echoing erroneous newspaper coverage. When the multi-ton loft crashed to the stage floor it shook nearby

structures and made an "explosive" sound that morphed into an explosion with retelling. The same was true of the aerialist wire. There was an aerialist's suspension wire laying on the stage floor but it did not come in contact with the fire curtain. The fire curtain caught up on a vertical lamp strip on the north side of the proscenium arch. Scores of witnesses described

seeing stage workers struggling to unsnarl the

curtain from the lamp strip before flames and smoke drove them to evacuate the building, and a half dozen stage workers testified about that struggle. |

|

Story 3036 |