|

Call Ernie

As a performer, composer, and director,

forty-three-year-old Ernest (Ernesto) M. Libonati

(1860–1935) had in 1903 been a fixture in Chicago

musician circles for over a decade. He could have

been a regular in the

Iroquois Theater orchestra or

a fill-in musician for a single performance. His

primary instruments were the violin and mandolin,

but he also played the flute and almost certainly

the cello, piano, and xylophone as well. That kind

of instrument versatility and his connection to many

other Chicago musicians, including family members,

might have put his name near the top of the list for

Chicago orchestra managers.

In an era with a live orchestra in every theater and

at many social gatherings, keeping chairs filled

would have been a challenge. The Rothschild

department store on State and Van Buren even offered

live music in its restaurant for the weekday lunch

crowd. Phonographs were popular in homes, but the

invention of amplifiers for large venues was six

years away.

For the Wednesday afternoon matinee on December 30,

1903 Ernest played the violin — alongside his

college-age son, Michael. The Iroquois orchestra's

regular cello player was absent, so

twenty-one-year-old Michael Ernest Libonati filled

in. Michael, who sometimes went by his middle name,

was a student at the University of Michigan, home

for the holiday, probably glad to earn a few extra

dollars.*

Escape

Father and son Libonati

escaped from the Iroquois without injury.

Ernest saved his violin but the cello

was left in the orchestra pit. When it caught

fire, orchestra director

Anthony Frosolono decided it was time to flee.

Upon opening the primary door from the orchestra

pit to the basement beneath the stage, they were met

with flames. They took another corridor

instead, breaking down a door to get to the costume

department and engine room, and on to stairs leading up to the back of the stage and out to the Dearborn street

exit. The basement by that time was

sufficiently smoke-filled that

some performers escaped through a coal chute and

manhole in the street. Thirty years later

Ernest described having grabbed a six-year-old

performer and pushing him up through the coal chute.

A fiddler's life

Ernest and his wife, Flora (Fiora) Pellettieri†

Libonati (1863–1953), immigrated to the United

States from south-central Italy with their parents

in 1872 as youngsters. Ernest's parents were Michael

and Rosa de Roma Libonati.

Ernest and Flora married in 1881 and by 1903 had six

children aged seven to nineteen, three sons and

three daughters: Michael, Rosamond (

biography),

Isabella, Elliodor, Ellinore (Mariassunta), and

Roland. A seventh, Luigi, died as a toddler. For

most of those years, the family lived in a flat on

an upper floor at 416 and the adjacent 420 South

Clark in Chicago.‡ Other family members shared the

address over the years, including Flora's sisters

and their families, Maria Emanuello Pellettieri

DeStefano and Josephine Pellettieri Franco.

Josephine, her husband Frank, and their sons were

also musicians.

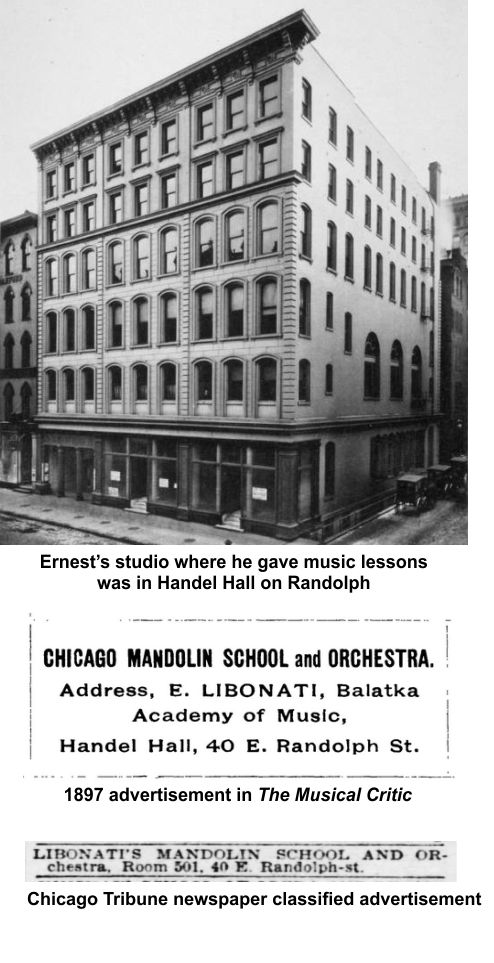

In addition to hiring out to orchestras, Ernest gave

music lessons, in the 1890s directed his own

band/orchestra, and composed music. In 1903 his

music studio was in room 501 at the Handel Hall at

40 E. Randolph, next to Marshall Field department

store and a few blocks from the Iroquois Theater.

(Handel Hall had previously been known as the

LeMoyne Building and housed the Western News

Company.)

|

|

The instrument for which Libonati was best known was

the

mandolin.

He gave lessons on the instrument and was the

director of the Chicago Mandolin Orchestra. In 1902

appeared sheet music for three of Ernest's polka

compositions for mandolin and piano: Jewels of

Joy, Heart's Delight, and Kiss in a Letter, as

well as Echo's of the Past for mandolin and

guitar. Ernest also sat First Chair in the Bohmann

Quartett, a group of Chicago musicians sponsored by

the Bohmann company, manufacturer of mandolins and

guitars. (See accompanying advertisement.) Other

members of the quartet included Ernest's three

brothers-in-law, fellow mandolin player Charles

Pellettieri, John (Giovani) Pellettieri on flute,

and Francesco Franco on the harp. Prior to his

involvement in the Chicago Mandolin Orchestra,

Ernesto was the First Soloist of Valisi's Florentine

Orchestra and the Tomaso Orchestra. Ernest was a man

at the right time and place to cultivate the Golden

Age of the mandolin.

Ernest's survival at the Iroquois Theater helped

ensure the education and success of his children.

Four of six graduated from college — a major

accomplishment in an era when fewer than ten percent

of the population did so. Three became attorneys and

politically active, Ellidore as an outspoken

opponent of communism and fascism, Roland as an

elected official, and Michael with a run for an

assistant judgeship. One daughter married a baron

and another a doctor.

Roland represented his Illinois district in the

House of Representatives from 1957 to 1965. A

colorful character, nicknamed Libby, Roland served

in the 86th Division Infantry during World War I.

Afterward, he graduated from the University of

Michigan and Northwestern, passing the bar in 1924.

(The Libonati focus on scholarship continued when

his son, Michael E. Libonati's namesake, became a

law professor.) In a 1977 interview, Roland briefly

mentions his father's music studio.

(

Family remarks start around 6:42.)

Substitute cello player at the Iroquois, Michael E.

Libonati (1882-1919), the oldest of Ernest and

Flora's boys, graduated from the University of

Michigan and became an attorney. He started a

wholesale poultry business in Curryville, Missouri,

and experimented with politics, but in 1918, with

his two younger brothers overseas in World War I

combat, he put his legal career on hiatus.

Too old to enlist, he joined the Knights of Columbus

in France as an overseas secretary to assist

American Expeditionary Forces fighting in Europe.

Known as Caseys,

K of C volunteers operated clubhouses for soldiers,

delivered supplies, performed first aid to the

wounded, and visited them in hospitals to provide

stamps, stationery supplies, and letter-writing

help. It was in that last service where Michael may

have contracted the illness that took his life in

March 1919, four months after the end of the war.

According to a

1921 Knights of Columbus history by Joseph J. Johnson,,

Michael contracted

influenza during the worldwide 1918–1919 pandemic that killed

over one million American soldiers (about

1/3 from doc top). His funeral service was held in

France, led by Chaplain Arthur L. Girard, a Chicago

clergyman, known attendees being Chaplain John

O'Hearn and James Daly, also Chicago men, Daly a

fellow Casey. Michael's grave marker states he died

in Coblenz (Koblenz), Germany, but his college

alumni newsletter reported that he died at the

Evacuation Hospital at Wolferdange, Luxembourg,

about two hours away, of pneumonia meningitis.

Not all good memories for Ernest

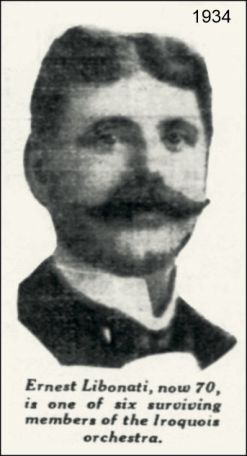

At a 1934 gathering of the Iroquois Memorial

Association on the thirtieth anniversary of the

fire, Ernest spoke reflectively of his children's

success but also of life's disappointments,

including Michael's death, the only musician amongst

his children. He mentioned too that they had lost a

lot of money in the 1929 stock market crash. Ernest

was seventy years old and one of only six surviving

members of the Iroquois orchestra.

In his recollection, the fire curtain had caught on

an aerialist guide wire. It didn't; at legal

inquests, a dozen stage workers testified about

their struggle to release the fire curtain from the

strip light obstacle. From the orchestra pit, Ernest

could not have seen the obstacle or the struggle,

but it is interesting that perhaps he did not follow

disaster coverage in the newspapers. It might be

he'd had enough of the Iroquois. He never played in

the structure again.

|

|

Discrepancies and addendum

Another Libonati made it big

in Ragtime. In the early 1920s, the musician in the

family with celebrity recognition was ragtime

xylophonist Caesar Jess Libonati (1885–1965),

Ernest's younger half-brother. Jess recorded several

records and toured the country. Prior to his success

with the xylophone, he performed as a drummer in the

Buffalo Bill Wild West show. A charismatic and

colorful fellow into old age.

* Back in Ann Arbor, when school was in session,

Michael Libonati worked as a part-time waiter at Prets,

formally known as the Campus Club and

Prettyman's

Boarding House,

where he served the athletes who made it home —

Michigan Wolverine's varsity football and their

legendary coach,

Fielding Yost,

who led them to six national championships and ten

Big Ten Conference titles during his twenty-five

years coaching the team.

† Sometimes misspelled as Pelletire or Pallatira.

‡ According to a biography about daughter Rosamond,

among the ground and basement level retail

businesses below their family's flat was a bakery

owned by her uncle DeStephano and for a time a

restaurant or bar with which Ernest was owner or

manager. I failed to find anything about Ernest and

a bar or restaurant. The Rosamond biography

relegates Ernest to a near footnote: Rosa

Libonati's father was also a musician who played for

the family's parties. Eventually, he played music in

a small Italian orchestra in halls and restaurants. As

though music were Ernest's hobby, a diversion from

his restaurant business. The evidence reveals a much

different picture. From his arrival in Chicago in

1888 until his death, the only newspaper references

to the man other than his obituary were relative to

his musical career. For U.S. Census reports, he

described his occupation in 1900 as a music teacher,

in 1910 as a violin professor, and in 1920 as a

musician in a cafe. In Chicago city directories for

twenty-three years, 1888–1911, he described himself

as a musician and/or music teacher. For many years

he ran classified advertisements in the Chicago

Tribune for mandolin lessons and rented a studio in

which to conduct those lessons. Rosamond described

her mother as the ambitious disciplinarian in the

family. Perhaps Flora's ambition and Ernest's

passion were not always aligned.

|