|

Josephine (b. 1864) was the daughter of Irish

immigrants, the widow Catherine "Cate" Gibbon

Munholland (1833–1918), and the late Robert

Munholland (c1835–1887), a civil war veteran.▼2

She and her four siblings grew up in Bloomington,

Illinois, where she graduated from high school in

1882. Her sister Kate died the following year, the

same year Josephine was elected as an officer in the

National Ladies Aid Society, associated with the

Grand Army of the Republic. She would later

participate in another organization connected with

the G.A.R., the Women's Relief Corps. (Her brother,

Thomas Munholland, shared her commitment and, until

relocating to California at the close of the 1800s,

was active in the Cedar Rapids, IA National Guard.)

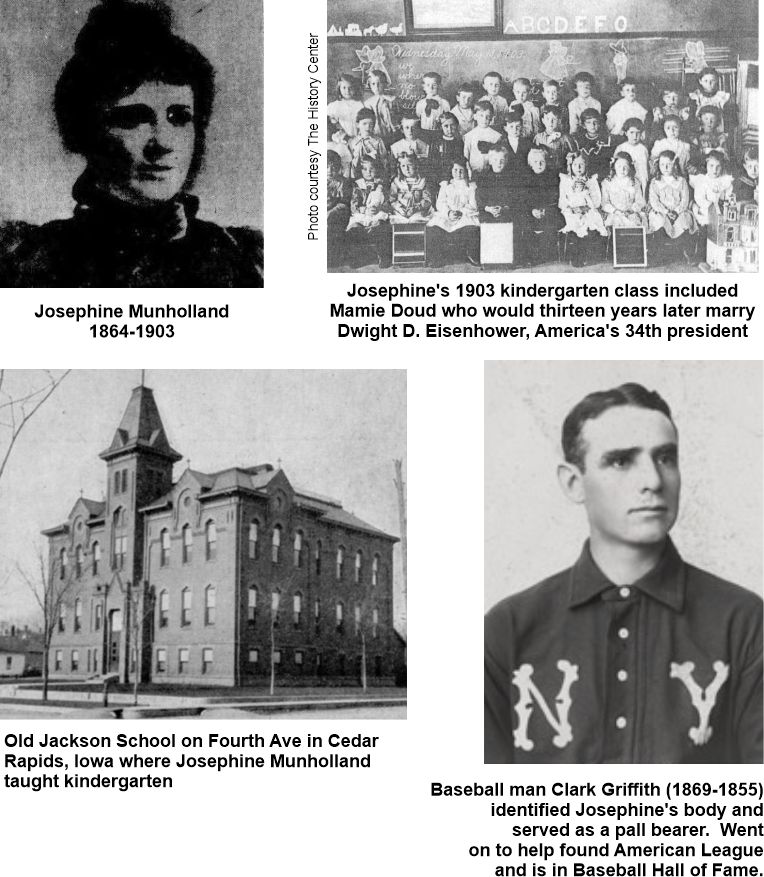

Josie moved to Cedar Rapids, about three hours

northwest of Bloomington, around 1898, first working

as superintendent of the Universalist Church school,

then becoming a public school teacher, assigned to

the Jackson school on Fourth St. In 1903, she lived

at 615 West Ninth Street or at 865 Fifth Street or

at 1031 Second. (All three addresses were reported.)

When Josephine did not arrive for dinner at the

Griffiths, they contacted the McFarlands. By then,

news of the fire was quickly spreading through

Chicago by word of mouth, and the McFarlands and

Griffiths began searching Chicago hospitals and

morgues. The search went on for days before finding

Josephine's body at Rolston's funeral home. She was

officially identified by Clark Griffith.

Later known as the Old Fox,

Clark

C. Griffith became a fixture in baseball history as a pitcher,

manager, and owner. He and Anne "Addie" Robertson

(1876–1957) had married in 1900. Prior to her

marriage to Clark Griffith, Addie attended social

outings in Cedar Rapids with the McFarlanes, Pecks,

and Munhollands, including Josephine and her

brothers. Clark was a pallbearer at Josephine's

funeral, along with her brother-in-law, Charles

Stephenson, and friend, George Peck.

Some newspapers reported that Josephine's sister,

May Gibbons Munholland Stephenson, and her husband, Charles

Stephenson, a clerk in the Chicago & Alton Railway

trainmaster's office, traveled to Chicago to accompany

Josephine's body to Bloomington. Newspapers also reported

that May was unable to attend her sister's funeral due

to her three children being ill. (They were Warren,

Robert, and Catherine, all under eight years of age.)

|

|

White lie to a grieving mother.

Josephine's mother, the widow Cate Munholland, did

not see her daughter's body but reportedly spoke

with the physician who examined the body and was

told that her daughter's death was instantaneous

from gasses.

The undertaker, however, John A. Beck of

Bloomington, persuaded Cate not to view the horrific

remains of her daughter's burned and mutilated body.

That fits with reports of the McFarlands and

Griffiths having conducted a long search for

Josephine's body.▼3 They failed to recognize

Josephine's body because it was damaged beyond

recognition.

The truth was too ugly

Cate Munholland was not the only grieving parent to

be told that her loved one died instantly and

without pain. It was such a constant refrain in news

stories interviewing Iroquois victim family members

that I no longer give it much credence. In

contradiction are many stories from first

responders about hundreds of charred bodies,

many carried out in pieces, and many family

members who searched for days to find their

loved ones only to realize multiple searchers had

passed by the unrecognizable body multiple

times. According to interviews with family members who related what

they were told by funeral directors and family doctors, no Iroquois

victim suffered but there were many, many closed casket funerals.

Funeral

Josephine's funeral service was conducted by the

Reverend John A. Mueller. He was a personal

friend and pastor of the Unitarian Church at East

and Jefferson Streets in Bloomington that she had

attended as a young woman. Mueller closed the

service with a description of Josephine's cheerful

nature, capacity for hard work, and positive

influence on young people in the church and at

school. Josephine's brothers, Thomas Munholland

(1861–1921)▼4 and John Munholland

(1959–1917), were businessmen in Los Angeles

and Long Beach, California. Distance prevented attendance

at their sister's funeral.

In the years after the fire

Josie bequeathed $1,000 to her sister May

Stephenson for the education of her nephews,

Warren and Robert.

In the odd coincidences department, Josephine's

sister and her husband, May and Charles Stephenson,

ended up in Elkhart, Indiana, my hometown, and are buried here in Rice Cemetery. On the other side

of town, in Grace Cemetery, is the family plot

of the infamous Iroquois manager,

Will J. Davis.

|

|

She would have if she could have

First appeared in Rockford, IL newspaper

Heroic Josie story doesn't hold water.

The probability of a woman alone forcing her way

through a stampede of nearly two thousand terrified

people is close to nil but

since the newspaper story didn't claim she

succeeded, only that she tried, it is

possible. Less credible is that anyone who

knew her saw her make that attempt.

Josie went alone to the theater so had no

companions to tell of her noble action.

She died at the theater so had no opportunity to

talk about her experience with a nurse, for

example, in her last minutes of life. The

only way Josie's activity at the Iroquois could

have been reported is if someone at the theater

recognized her and carried the tale to Josie's

family. She was visiting the city from her

home 245 miles distant.

Josie had grown up in Bloomington, IL and lived

in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. There were four

survivors of the Iroquois fire who had lived in

Bloomington, IL, Josie's hometown: Charles and

Dora Adolph and Charles and LaVisa Bibel.

Did they recognize Josie as they fled the

theater with roughly two thousand others?

More apt to have recognized Munholland were fellow teachers from Cedar Rapids: Mabel Cooper

and Charlotta Stout. That they saw her in

the theater prior to the outbreak of the fire is

believable. That they saw her in the

chaotic evacuation, not so much.

It is a tribute to Josephine that she was viewed by those who

knew her as someone too vibrant, determined, and courageous to

have gone out meekly. In life, their Josie had stood far out from the crowd,

so she must have done so in death as well. In reading newspaper

clippings of her life prior to the fire, I saw glimpses of a

person who, if able, would absolutely have gone back into the

burning theater to save others. In an era in which women were

expected to be demure, Josephine Munholland traveled, chaired

committees, hosted social events, judged art at the county fair,

had many friends, performed in literary recitals and songs at

parties and in amateur theater. Her performance as a

kindergarten teacher helped motivate Cedar Rapids to make

kindergarten an established part of the curriculum. She was a

lady to be reckoned with. So 1904

newspapers made her a superhero. No

harm, no foul.

|

|