|

Kersten and Green gone,

Kavanaugh takes over

The first grand jury had

indicted Iroquois Theater manager

Will J. Davis in February 1904. That

indictment was quashed a year later by judges

George Kersten and Peoria judge

Theodore N. Green. Judge Kersten showed

the prosecution what needed to be changed in the

case for a successful do-over. Based on Kersten's

recommendations a second grand jury issued an

involuntary manslaughter indictment against Davis in

March 1905 and the case was turned over to circuit judge Marcus

Kavanaugh (1859–1937).

Another six months of legal manuevers

Three months later in a six-hour argument made before Kavanaugh in mid June 1905,

defense attorneys petitioned the court to dismiss

the March 1905 manslaughter indictment. Chief

defense attorney

Levy Mayer based his argument on two points: 1.)

the state's case rested on the inaccurate

presumption that Davis owned the theater structure,

and 2.) the fire ordinances in place at the time of

the fire did not make Davis responsible. Judge

Kavanaugh found another flaw in the indictment:

conflicting entities were named in the case.

The company was sometimes referred to as the

Iroquois Theater Company and sometimes as the

Iroquois Theater Amusement Company. Such is the

stuff of appeals. Nonetheless, Kavanaugh took

the motion under advisement.

Try him

On January 24, 1906, despite Mayer's extensive argument and typos, judge

Kavanaugh upheld the involuntary manslaughter

indictment, letting the trial go forward. If found guilty, the

penalty was a prison sentence of one year to life.

Erasmus C. Lindley of

states attorney John Healy's office had argued

that the obligation to provide fire escapes rested

on common law as well as municipal ordinance thus

was not dependent upon enactment by the Chicago city

council, but Kavanagh dismissed the two common law

assertions. In a

lengthy article three days before his ruling,

the Chicago Tribune laid out what Kavanagh would

consider, including a summary of legal proceedings

to that point.

On to Judge Ben Smith

Four days later, Mayer demanded a change of venue for the

trial. (It was the second venue change discussion in

court, the first having been voided in February 1905

when

judge Kersten quashed the state's faultily-drafted

indictment.) Prosecutor Healy objected to a

venue change because of the cost of transporting

many dozens of witnesses. Newspapers suggested

public hostility against Davis had diminished,

citing as examples that the Iroquois building was

back in use as a theater and that demonstrations of

grief and anger at annual gatherings of the Iroquois

Theater Memorial Association were less pronounced.

Six months later,

judge Ben Smith ruled that the venue could be moved.

Kavanagh an interesting character

The son of Irish immigrants, Marcus and Mary Hughes Kavanagh* of

Iowa, he received law degrees from both Niagara and

Notre Dame universities and was admitted to Iowa bar

c.1878. He served as city attorney of Des Moines and

as a circuit court judge.

Kavanagh moved to Chicago in 1889 and went into

partnership with judge John Gibbons and J. V.

O'Donnell. In 1891 took time away from his career to

command the 7th Illinois regiment during the

Spanish-American war, achieving the rank of colonel.

|

|

In 1898 Kavanagh was appointed to the bench in Cook

County by Illinois governor Tanner to succeed judge

John Barton Payne. He was a judge in Cook County

Superior Court from 1898 to 1935. He was one of four

who ran against Carter Harrison Jr. in the 1901

Chicago mayoral election.

With a reputation as a tough-on-crime judge and standing

over six-foot tall, Kavanagh was an imposing figure. Three times

in his career, he imposed the death penalty on men

who had pled guilty and expected lifetime

imprisonment. He was known for his opinion that

attorneys should not defend men they knew were

guilty. After he was invited in 1929 to participate

in the

Wickersham Commission investigation into

criminal justice reform, he became a regular on the

lecture circuit. In 1930 he appeared before the

House of Commons in England to urge lawmakers to

retain capital punishment.

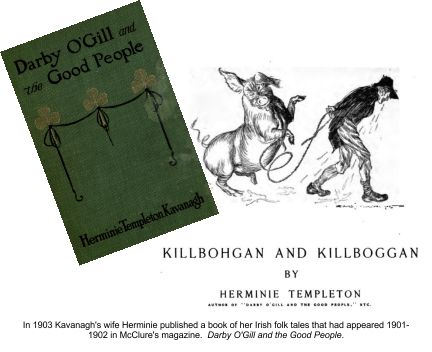

His first wife, married in 1908, was

Herminie McGibney Templeton Kavanagh

(1861–1933), author of Irish folk tales, including

Darby O'Gill and the Good People in 1903 that

fifty-six years later became the basis for a

Disney film by the same name (trailer).

After her death, at age seventy-five, he married his

twenty-seven-year-old secretary of six months,

former model and stenographer Jeanne Velma Latour.

In 1910 Marcus authored an anti-Darwin pamphlet,

"Proof of Design in Creation," and in 1928, a book

about crime, The Criminal and His Allies. In 1911 he ruled that fingerprints were admissible evidence — a historic

first.

Kavanagh retired in 1935 and moved to Hollywood,

California, where he died two years later.

|