|

Enlarge

|

|

From Rochester to Minneapolis

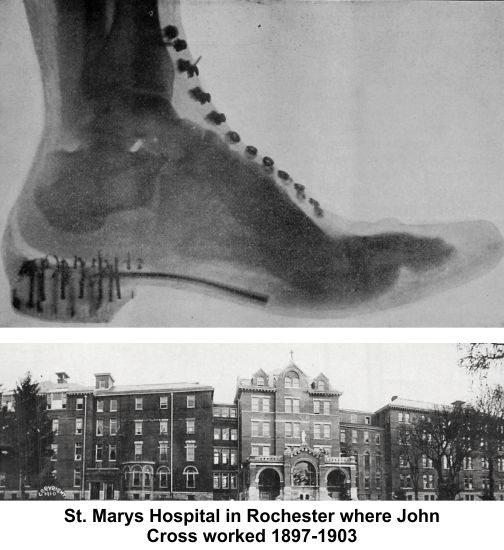

For the first seven years, Dr. John G. Cross (1870–1928)

practiced medicine in his hometown, Rochester,

Minnesota, at St. Mary's Hospital. He had graduated

from Northwestern in 1895, the year German scientist

Wilhelm Roentgen discovered x-rays. Not unlike young

people today with an affinity for technology that

sometimes challenges their elders, John's mastery of

radiography soon brought recognition from older

physicians in Minnesota.

One of those was the influential Dr. William J. Mayo

(1861-1939), co-founder of the Mayo Clinic, with

whom John Cross worked at St. Mary's. At an 1899

medical conference, Mayo praised the excellence of

John's Roentgen skiagraphs (x-rays), no small

feather in the cap of a man just four years out of

medical school.

Perhaps he would have become part of the Mayo Clinic

had John remained in Rochester, but in mid-1903, he

became part of the visiting staff at Minneapolis

General Hospital as a clinical bacteriologist in the

pathology department. By December, he was preparing

to leave Rochester to accept a full-time position at

Minneapolis General.

Iroquois Theater

On December 30, 1903, Dr. John Cross was in Chicago and had just left the

Reliance Building on Washington Street when he

was drawn to the fire alarm. He saw nothing of great

note so walked on to the Marshall Fields Department

store. By then, the injured had begun to appear a

makeshift first-aid area was being set up in the

store. An elevator operator persuaded him to assist.

Bio bits

John was the son of a

Dr. Edwin C. Cross and Fanny Marcy Cross. He

graduated from the University of Minnesota in 1891,

married Frances L. Montgomery in 1894, and received

his doctorate from Northwestern in 1895. Over the

next eight years, he and Frances had three children.

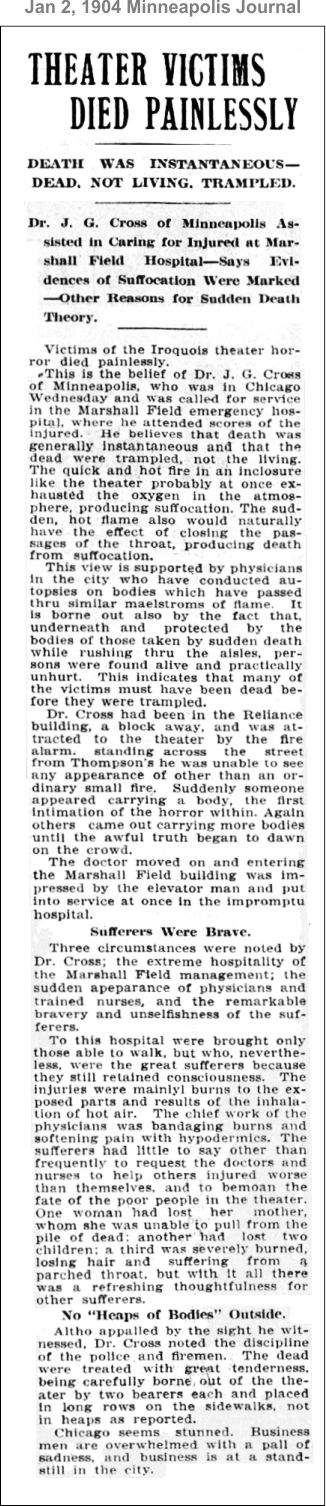

Misleading interview and newspaper story (left)

This story tries my patience. Before the fireball at

3:50 pm, the only instantaneous deaths inside the

Iroquois auditorium happened when a few people

jumped from a balcony to the first floor, killing themselves or those they

landed upon. After the fireball, virtually NO ONE

exited the auditorium, so all trampling had stopped.

When firefighters gained entrance shortly after the

fireball, the theater was nearly silent. It was

filled with four hundred corpses. They found "a few"

people beneath corpses, spared the flames. So few

that the only one I've found identified in news

stories was

Elizabeth Clingen. E. Dr. Cross's theory that

people only trampled the dead is nonsense. They

trampled the living until the living became the dead

as a result of that trampling, then they trampled

the dead until the fireball came. After that, there

was no one left alive inside to do any trampling.

At best, the doctor's remarks are an example of why

it's a poor idea to go public with an opinion before

all the facts are in. At the Coroner's inquest into

the cause of the Iroquois Theater disaster, witness

testimony revealed a pattern that was repeated over

and over. Knocked or pulled to the floor by others,

misfortunates begged and pleaded for help in

regaining their footing. People who tried to give

them a hand were pushed by the oncoming crowd behind

them to keep moving. Some of these were knocked down

and became trampled themselves. Those who lived to

testify about their experience had kept moving.

Shouting, "Wait!" doesn't work in an environment

with hundreds of screaming people.

Terrified people who can't find loved ones in a

life-threatening situation become loud. Those coming

up the aisle from behind couldn't see a downed

person ten people ahead, in the dark, and they too

were being pushed from behind. If the chain-reaction

sequence started at the front of an outer aisle

(front = closest to stage), where there were fewer

people trying to exit, there were fewer layers in

the pile, and the downed victim had a better chance

of extricating himself and standing. If it happened

in the middle of a center aisle, he suffocated under

the weight of hundreds of pounds of other human

bodies compressing his chest, making it impossible

to expand his lungs enough to inhale the

smoke-filled air. The story has the distinction of

being the only one in which references elsewhere to

piles of corpses inside the theater were confused

with first responders' treatment of the dead.

In the years after the fire

John became a fixture

in the Minneapolis medical community, serving as

president of the Hennepin County Medical Society and

Chief of Medicine at Minneapolis General Hospital,

as well as practicing at other area hospitals,

including Abbott and Hill Crest. He was also a

faculty member at the University of Minnesota in

Minneapolis.

|