|

Nurse Rachael

Around 1900, Rachael Gorman went to work as a roommate of and nurse for

William Held's Home for Epileptics. In another

decade would come the development of Phenobarbital,

but in 1900 "epilepsy" was an umbrella term used to

reference a group of conditions that included mental

illness, demonic possession, and syphilis. Held

promised to cure them all. The only thing Rachael

nursed was wallets, and she did it well, too well.

When her earnings outstripped Held's, they quarreled

and parted company. He said she drank too much and

was dishonest in her financial reports.

Rachael clones

She formed a new partnership and expanded. She hired a half dozen

assistants and trained them in the art of charity

solicitation, giving her the capacity to better

penetrate Chicago and move into other cities. Donned

in green robes patterned after those of Catholic

nurses, including a cross necklace, the "Green

Sisters," as they eventually came to be called by

law enforcement, looked and sounded like sisters of

charity. Unlike other groups of sisters,

however, Rachael and her girls were connected with

no church or religious order. Their

collections went to support themselves and their

bogus treatment facilities.

Iroquois Theater story

At the time of the Iroquois Theater fire, public exposure of Rachael's

game was a year off, so the Inter Ocean

reporter gave her the benefit of the doubt when

hearing her story the evening after the fire. It is

not likely she was anywhere near the painters'

planks over Couch Place. More probable is that she

overheard conversations about the plank crossings

while at the

Sherman House, Marshall Field's, or another of

the sites where survivors and reporters congregated

that first night. Ever a quick study, Rachael

inserted herself into the storyline, probably to

work a charity angle. The Inter Ocean

reporter may not have been sure she was lying, but

I think he and/or his editor had reservations. Based on other stories about the

plank, the reference to Rachael was brief. The Chicago Tribune

didn't bite on it, nor did

Coroner Traeger; even though Traeger made a

point of calling other plank crossers to testify, Rachael did not testify. Logistics

made it unlikely that she hung out at the windows of the

Northwestern dental department. The narrow windows were crowded with painters

trying to keep the planks anchored and she would have been in the way. It was the kind

of story embroidery added by someone who wasn't there — while working the crowd for

donations.

One of the 2003 anniversary books about the Iroquois Theater fire, Tinder Box,

picked up and repeated the reference to Rachel's heroism, missing subsequent newspaper stories

about her chicanery. Author Anthony Hatch accumulated data over many years and

were it not for his efforts there are aspects of the disaster that would not be known

but a con artist nun slipped past him.

|

|

Staging the scene

As was

common for the time, American Chronic and

Epileptic Association also made outrageous promises

of cures, but for Rachael and her cohorts, tonic

sales and patient fees were a secondary revenue

source at best. They were props and camouflage in a

carefully engineered con that pried money from the

pocket of

William Jennings Bryan and scores of other

politicians and businessmen. She often targeted

winning bettors at racetracks and maintained a

little black book of her regular marks. Political

and trade conventions were lucrative, including the

St. Louis World's Fair in 1904. Rachael's assistants

were also assigned to trains, saloons, and

restaurants. Rachael's personal twist on the scheme

was to party with her mark, while garbed as a nun,

until he became boastful about his track win or

other financial success, then hit him up for a

donation.

Round Lake farm

After several partnership dissolutions and restructurings, Rachel went solo

and formed the Rachael Gorman Home for Epileptics.

For a time, it operated a "treatment center" at a

farm in Round Lake, IL, north of Chicago. A whopping

seven patients were sent there during its eighteen

months of operation.

Blue Island home

In 1904 she purchased a home in Blue Island to accommodate her patients and

maintained an office in downtown Chicago as an

operational hub. She needed a place for her troops

to change into their nun uniforms and receive her

instructions about travel and targets. It was a busy

time. Two of Rachael's former partners had begun to

imitate her solicitation methods, including corps of

nun-garbed solicitors. In early 1904, roughly

eighteen of them worked the Midwest, each with their

own robe color.

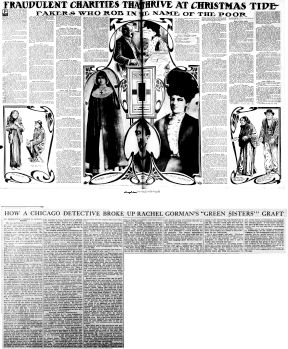

Shut down and exposed

In October 1904 came a tip about bogus epilepsy treatment facilities from Dr.

James A. Egan, Secretary of the Illinois State Board

of Health. The police became determined to shut down

Rachael and her imitators, raiding her office on

Wisconsin St. Enough evidence was found to move on

to her house in Blue Island. There, police

discovered she had only two patients and three

servants who put on "seizure shows" in the front

yard to dissuade curious neighbors or authorities.

She was forced to close her "hospital" and

threatened with imprisonment if she continued

charity solicitations.

Read two major Chicago newspapers in 1906 & 1907 exposing Rachael Gorman.

|