|

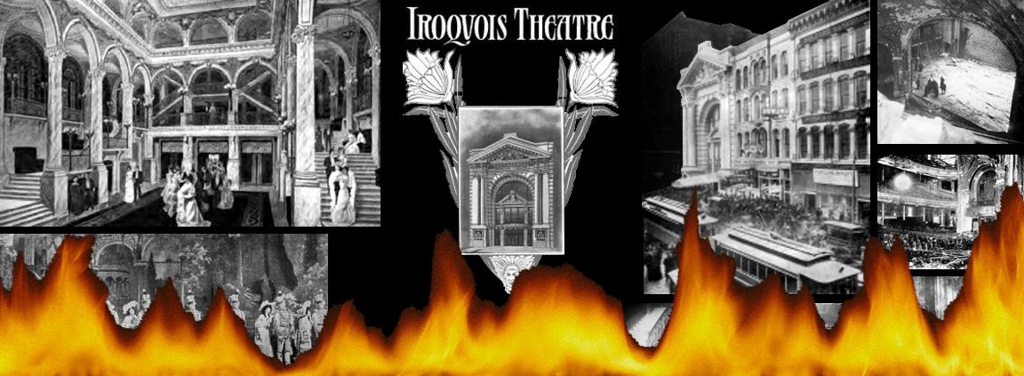

Speculative impressions from a speculative Iroquois performer:

On December 30, 1903,

orchestra musicians for a musical variety show had an

afternoon gig at Chicago's newest playhouse, the Iroquois

Theater on Randolph St. With the Christmas holiday coming to an

end in two days, the matinee performance of

Mr. Bluebeard had attracted a packed house of families,

enjoying a last celebration before school restarted. It was one

of

Klaw & Erlanger's big shows with hundreds of performers,

lots of lights, and even aerial dancers.

The second act had just begun, and on stage

eight couples, dancing and singing. The tune was a light

Jerome and Woodward tune,

In the Pale Moonlight. Other than it being hard to see,

what with the stage in near darkness to look like a moonlit

garden, it was usually uneventful. The next number with

Eddie Foy and his elephant would be more lively and

challenging. There were a number of sound effects timed to the

act, and audiences loved it, especially children, and there were

more of them today than he'd seen in prior performances. It

reminded Otto of his daughter, Ruth.

His first hint that something was amiss came when he heard a

slight faltering in the dancer's footsteps and voices. Otto kept

playing his flute but turned in his seat to look over his right

shoulder toward the stage. He saw the source of the problem

immediately. Curtains at the top right of the proscenium arch

were on fire, and the flames were rapidly traveling across the

width of the stage.

In the next fifteen minutes nearly six hundred people would die,

including Otto. Nothing is known about his last minutes.

|

|

|

Thirty-seven-year-old Otto H. Helms taught flute at the Chicago Conservatory of

Music. It is conjecture that he was in the Iroquois

orchestra. Though his name was listed in Iroquois

Theater victim lists, none mentioned that he was a

musician. Nothing was reported about a theater

companion, however. If he was in the orchestra,

given the attention given to Nellie Reed, the aerial

dancer who lost her life in the fire, it's odd

newspapers didn't mention his connection to the

performance.

He married in 1895, but in 1900 he and his family —

wife Alma Campe Helms (1874–1945) and only child, a

daughter named Ruth Helms (1897–1960) — were living

apart. Alma and Ruth lived with Otto's parents, and

Alma was described in the U.S. Census as widowed, a

common description in an era when divorce was

verboten. On the other hand, there is evidence that

he suffered from some sort of mental illness (see

below) that might have caused temporary marital

disruptions. At the time of his death, they seemed

to have reconciled.

Otta was the son of German immigrants Christine and

Christian Helms, both deceased before his death. He

had eight siblings, one of whom, Walter, identified

his body after the Iroquois Theater fire.

Otto was buried in Wonder's Cemetery in Chicago with his parents. On January 3,

1904, his funeral was attended by brothers in his

Garden City Freemasons Lodge #141.

Music was the family business

In becoming a musician, he followed in the footsteps of his father and older

brothers — Christ, a bass trombone player, and

Richard, who played the double bass. In addition to

teaching flute at the Chicago Conservatory of Music

and Dramatic Art at the Auditorium,* he performed in

various amateur orchestra and chamber music groups,

including the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. In city

directories, he was listed as a music teacher.

Arrested for threatening Teddy Roosevelt

Six months prior to the Iroquois Theater fire, Otto was arrested for sending

threatening letters to president Theodore Roosevelt

and underwent a sanity hearing. The report was

brief, only saying that it involved a $20,000

insurance dispute. He wanted to debate with the

president.

To newspapers insisted he meant no harm to the

president. He was sent to the hospital

for the insane in Elgin but six months later had

apparently been released. His three brothers

may have helped. I found no evidence of a

second Otto Helms in Chicago in 1903 but did find

two other Alma's. Otto had a sister named Alma

and one of his brother's also married an Alma.

|

|

Teddy

In the years after the fire

Otto's widow didn't have a knack for picking husbands. Alma remarried in

1906 to Charles Putnam, an officer in Newell-Putnam

Manufacturing, a button company, but four years

later sued for divorce, accusing him of cruelty.

Daughter Ruth, then nine years old, testified about

her stepfather dragging her mother from one room to

another by the hair and severely bruising her

mother's arm in another altercation. Putnam

protested that Alma was a battle-ax, but the judge

granted Alma a divorce.

Ruth graduated from a

private girls school, Milwaukee-Downer Seminary in

Milwaukee, and attended Northwestern for three

years. In 1919 she married her first husband, film

and radio star

Conrad Nagel (1897–1970), making her one of his

three wives. A pretty girl with vocal skills, Ruth

appeared in one silent film in 1920. She, Alma, and

her daughter by Nagel traveled Europe in the

1920s. She next married film director/producer

Franklin Sidney.

|