|

Alice Ripley Haskell Maxwell (1858–1948)

Alice was the only child of Sam and Abbie Haskell.

In 1875 she graduated from

Monticello Seminary

in Godfrey, IL near St. Louis, MO where the

principal was Helen Newell Haskell, her first

cousin once removed▼2

(At death Alice was the oldest graduate of the

school.)

At age thirty in 1888

Alice married a prosperous cotton broker who was

twenty years her senior. She moved often

in her life. Born in Massachusetts, she

spent her

childhood in Chicago, was a bride and mother

in New Orleans, lived in

Ontario from 1880 to 1899, came briefly back to New

Orleans just before her husband's death, then

back again to Ontario for a time, before settling for many

years in a Park

Mansions apartment in Pittsburgh. Her last years were

spent in a Fifth Avenue apartment in New York

City and she was buried in Ontario.

Alice's husband and sons

Robert Maxwell (1838–1900)

emigrated from his birth home in Ontario just

before the start of the Civil War. When the

conflict started, he joined the Washington

Artillery. He was promoted to sergeant in

1861, wounded at Rappahannock and left the

service in 1863. As a civilian he worked for

Everett, Lane & Co. and Wallace & Co., before

going into partnership Hugh Allison & Co., head

of a long-established New Orleans cotton

factorer. When Allison retired, Robert and

W. A. Peale went together to purchase control of

the firm and named their new enterprise Maxwell

and Peal. Both men served as a committee

head on the Cotton Exchange and Robert became a

director of the National Bank and president of

Mechanics and Traders Insurance. Toward

the end of his life Robert left cotton factoring

and became a partner in the dry goods wholesale

firm, Williams-Richardson, Ltd. He was one

of the governors of the original Howard Library,

built in 1889 on Harmony Circle. At death

his estate was valued at $31k ($1.1 mil), mostly

in stock in the National Bank,

Williams-Richardson Company Ltd., and

fertilizer-maker Standard Guano and Chemical

Manufacturing. Half went to his two young

sons and half to Alice.

Robert

Elliot Maxwell jr (1889–1946) Robert

served as a colonel in the Canadian Army during

World War I. After the war he went to work for

Carnegie-Illinois Steel for two decades where he

was in charge of exports. He left Carnegie to

form his own import-export firm, R. Elliott

Maxwell Associates. In 1941 he married a widow,

Mrs. Jean Spalding. He left no offspring.

Allison Ripley "Allie" Maxwell (1891–1929)

Shortly before an early death Allison became vice-president of Pittsburgh Steel.

He was a top-ranked amateur golfer. He married

Eleanor McCook and they had four children,

including Allison R. Maxwell Jr. who became

president of Pittsburgh Steel.

Alice's parents

Simeon "Sam" Dickenson Haskell (1830–1916)

came from Vermont and Maine and his wife, Abigail

James Hubbard Haskell (1831–1911),

from Boston;they married in 1855.▼3

Simeon Dickenson Haskell was a dry goods

commission merchant, his offices located at

23-25 Randolph St. — one of

five thousand

wholesale companies destroyed during the Great Chicago fire in 1871.

(The structure was rebuilt after the fire then replaced in 1902

with a six-story six-thousand-sq.-ft brick warehouse.)

The Iroquois Theater went up in 1903 across the

street. Sam and Abbie lived in the rebuilt Palmer

House hotel in 1877, the year that Sam

voluntarily petitioned the bankruptcy court

for protection. As a result of accounting and reporting

problems, the case lingered for

two years, with frequent newspaper updates.▼4

An ardent republican, in 1879 he decorated the windows of his State

St. offices in support of President General

Ulysses S. Grant's Chicago visit.

Down but not out, in 1899 he served as a spokesman

for the South Park Auto-Coach Company in

petitioning

the South Park Board for exclusive rights to operate

twenty or so thirty-passenger motor carriages on

Michigan Avenue in Chicago. Their plan was

to sell one-hour 25-cent bus trips through and

near the parks, with a 10% commission going to

the South Park Board. (Carl Benz had

invented the first bus in 1899 and Daimler

brought the first commercial passenger version

to London streets in 1899.)

Sam worked then as secretary for patent medicine

company, Klinck Medicine.

Though nothing official was reported about

Haskell's worth, it was rumored to be in the

$10-16 million range when he was at the top.

Abbie passed in 1911 and Sam left Chicago,

relocating to West Manchester, MA.

Alice's education at

Monticello was likely spurred by her mother.

Abbie Hubbard Haskell had attended Townsend

Female Seminary of West Townsend, MA 1844-1848.

She studied art and music but

Principal Hannah P. Dodge saw to it that her

students also received an advanced collegiate education,

including math, geography, literature,

chemistry, and philosophy, taught from the same

texts as male students at Ivy League schools.▼5

|

|

Helen Marie Hutchison Lancaster (1855–1927)

Helen was

one of five children.

In 1875 she had married Wisconsin native Eugene Abiel

Lancaster and by 1903 had given birth to two children,

the first lost at five months of age.

She is an enigma. Following

her mother's lead, she

performed the social duties expected of her

status, hosting teas, balls

and receptions, but was not interviewed.

Helen's husband and daughter

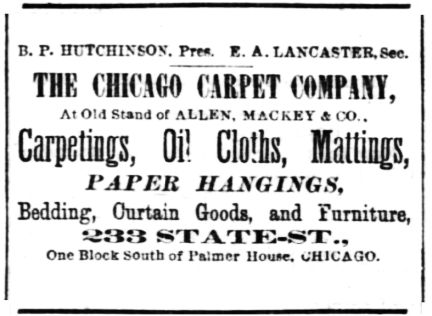

A native of Beloit, Wisconsin, Eugene Abiel Lancaster (1848–1932)

was a carpet merchant. He usually went

by E.A. Lancaster. Ben Hutchinson had

purchased the former Allen & Mackey Carpet

company for his son-in-law in 1876, a year after

his marriage to Helen, and the store was renamed

Chicago Carpet Company. In addition to carpet,

the store offered furniture, draperies and

oriental rugs. Located for over two

decades at 156-162 Wabash, at the corner of

Monroe St., the store contents were destroyed by

a fire in 1897. The following year John.C.

Carroll bought controlling interest and the name

was changed to Caroll & Lancaster. The

structure was rebuilt but by then Carroll &

Lancaster had moved across the street to the

opposite corner of Wabash and Monroe. When

Carroll died in 1905, his wife became involved

in the company and they relocated to 172 Wabash.

The firm could not survive the

1907 Panic and filed bankruptcy in 1908.

It's inventory was purchased by a Boston

company. In addition to its residential trade,

the store furnished theaters and public

buildings.

Kate Lancaster Brewster (1879–1947)

married Walter Brewster in January 1903.

She was named after her aunt, Kate Hutchinson

Noble.

Helen's parents and siblings

Benjamin P. Hutchinson

(1829–1899) and Sarah Ingalls

Hutchinson (1833–1900) came from

Massachusetts. They had six

children, of which four were still living in

1903. Known as "Old Hutch,"

Ben began his entrepreneurial life as a manufacturer

of shoes. He came

west in 1856 and after learning the

meat- packing trade in Milwaukee settled

in Chicago where he became co-founder of a meat

packing plant in the Bridgeport neighborhood. Burt, Hutchinson, and Snow

was said to be the first meat packing plant in

Chicago and in the Union Stock Yards when it

relocated there. He became an early

stockholder in the First National Bank of Chicago

and founded the Corn Exchange Bank in

1872. For a time his next enterprise, the Chicago Packing &

Provision Company, founded in 1872 by he and Sidney A. Kent, was the

largest meat processor in the country, employing sixteen hundred

people. Around 1880 Hutchinson turned his

businesses over to his son, Charles L.

Hutchinson (1854–1924), and focused on

grain trading, becoming a dominant force in the

pit from 1880 to 1885. His historical cornering

of the September wheat market took place in 1888.

Over the next three years his estimated $10

million fortune dwindled to $1 million with his

last big trade losing over $2.5 million. ($67 millions adjusted for inflation). In the

last eight years of his life he wandered to

Evansville, Boston and New York City. He slept in his

office while trading on the New York exchange

before giving it up. Reclusive, alcoholic and bitter,

he took a job clerking at

a second-hand store under the Brooklyn Bridge. His family brought

him back to Chicago and admitted him in the

Lakeside Sanitarium at Lake Geneva, Wisconsin,▼6

possibly hoping to cure the alcoholism, but he died there at age

seventy of heart disease.

You can read an entertaining/informative/sad

story of the trading adventures of Old Hutch

online.

Charles L. Hutchinson (1854–1924)

was Helen's older brother.

As a partner in his

father's commission brokerage, and Ben's primary

heir, Charles used his wealth and considerable

energy to help found the

University of Chicago and Chicago Art Institute.

(Helen joined him in philanthropy for the Art

Institute.)

At death, Charles' estate of $1.5 million

(inflation adj. $26 million) included a artworks

from his personal art collection that were

donated to the Art Institute (along with a $170k

donation — $3 million — from Charles and Helen). I failed to

learn exactly what works were included. A

newspaper obituary cited a list of artists

in the Hutchinson estate donation but many of

those named had actually been in the possession

of the Institute for over three decades.

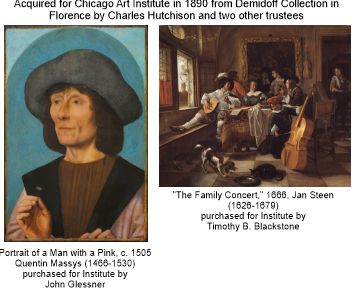

In June 1890 Charles had spearheaded the purchase of a collection of

thirteen Dutch and Flemish portraits from the Demidoff

collection in Florence, Italy, sold by a Paris

dealer representing Princess Helena Troubetskoi

Pratolino Demidoff. (Check out the

Institute's picture of one of

the receipts from that buy, listing a Rembrandt,

Van Dyck. Cuyp, teniers, and Van der Meer.) Monies

for the purchase came from Charles and other wealthy benefactors he

persuaded to contribute. In 1907 the 1890

acquisitions went on exhibit in the

"Room 32 Hutchinson Gallery of Old Masters," so

named as a tribute to Hutchinson's 25th year as

president of the Institution.

The Quentin Massys shown here was paid for by John Glessner

and

comes with an interesting history found on

the Glessner House blog.

As a partner in his

father's commission brokerage, and Ben's primary

heir, Charles used his wealth and considerable

energy to help found the

University of Chicago and Chicago Art Institute.

(Helen joined him in philanthropy for the Art

Institute.)

At death, Charles' estate of $1.5 million

(inflation adj. $26 million) included a artworks

from his personal art collection that were

donated to the Art Institute (along with a $170k

donation — $3 million — from Charles and Helen). I failed to

learn exactly what works were included. A

newspaper obituary cited a list of artists

in the Hutchinson estate donation but many of

those named had actually been in the possession

of the Institute for over three decades.

In June 1890 Charles had spearheaded the purchase of a collection of

thirteen Dutch and Flemish portraits from the Demidoff

collection in Florence, Italy, sold by a Paris

dealer representing Princess Helena Troubetskoi

Pratolino Demidoff. (Check out the

Institute's picture of one of

the receipts from that buy, listing a Rembrandt,

Van Dyck. Cuyp, teniers, and Van der Meer.) Monies

for the purchase came from Charles and other wealthy benefactors he

persuaded to contribute. In 1907 the 1890

acquisitions went on exhibit in the

"Room 32 Hutchinson Gallery of Old Masters," so

named as a tribute to Hutchinson's 25th year as

president of the Institution.

The Quentin Massys shown here was paid for by John Glessner

and

comes with an interesting history found on

the Glessner House blog.

Kate

Hutchinson Nobel ( ) was Helen's

younger sister. She had married attorney

Judah Noble and they had two children.

Prairie Street and Hyde Park

In 1880 siblings Charles, Willie, Helen and Kate Hutchinson lived with their

spouses,

children, and parents

Benjamin & Sarah Hutchinson, ten people all told, at 178 Park St. in Hyde Park,

with five servants. By 1900 they'd all

moved to three mansions on Prairie Avenue in the

Douglas neighborhood. There eleven

servants cared for the needs of ten people.

-

Helen Hutchinson Lancaster, her husband Eugene

Lancaster and daughter Kate Lancaster lived

at 2703 Prairie

with Sarah Hutchinson, Helen's recently

widowed mother, her brother, Williie

Hutchison, and three servants.

-

Helen's sister Kate Hutchinson Noble,

her husband, son and daughter (named after

Helen) and

lived at 2701 S. Prairie with five servants

to care for four people.

-

Helen and Kate's oldest brother

Charles L. Hutchinson lived at 2709 S. Prairie

where four servants took care of he and

his wife.

|

|

Discrepancies and addendum

1. In 1877 the Chicago Tribune cited

Hutchinson as one of the city's eleven wealthiest

men, in company with the likes of Marshall Field,

Levi Leiter, George Armor and George Pullman.

2. In thirty-nine years as head of Monticello Seminary,

1867–1907, puritanism seems to have been

Harriet N. Haskell's most remembered

characteristic. She twice sought to isolate

the school from sinful influences by purchasing acres of land adjacent to the campus

to prevent its purchase by entities she deemed

inappropriate as neighbors. She saw the word female as

uncouth and embarked on a long and ultimately

successful campaign to change the school's name from

Monticello Female Seminary to Monticello Seminary.

The short 1908 Harriet Newell Haskell biography by

Emily G. Alden can be read online. It does

not mention Alice Haskell.

3. Alice seems to have favored her association with her

mother's side of the family, with it's Boston

origins and connection to Mayflower ancestry.

It may not have been coincidental that the few times her

name appeared in newspapers Alice never mentioned her father

and only referenced her maiden name when dropping the name of her

prominent cousin Harriet Haskell at the Monticello

Seminary. She described her ancestry as Boston

based, omitting her father's Vermont heritage

altogether. No evidence of them sharing

a household once she reached adulthood. marry. I didn't find enough evidence to describe

her as a snob but noted that the few newspaper stories

about her, even her obituary, included mention of her prestige digs,

i.e., Park Mansions in Pittsburgh and 5th Avenue in

New York.

4. Haskell's creditors did not force him into

bankruptcy. He voluntarily

petitioned for relief.

Haskell had worked

as a commission broker for a decade prior to

the bankruptcy. By 1876 the operation consisted of his taking yarn on

consignment that he then sold for a commission,

sometimes reselling it outright and other times

contracting with knitting mills to have it turned

into garments he wholesaled. He also served as a

sales agent and wholesaler for producers of such

garments as shirts, socks, and underwear. A

knitting mill might sell Sam yarn or socks, or pay

him to sell their yarn to other knitters, or their

socks to merchants.

One example was

in process at the time of the bankruptcy filing.

It involved his $700 ($20k inflation adjusted) knitting order

with William B. Nourse's knitting company in

Michigan City, Indiana (that used state prison

inmates for labor). He'd provided yarn for the

contract to Nourse, from yarn consigned to him by

Crane & Water (C&W), who was also a producer of garments

that Sam wholesaled. The yarn belonged to C&W until a specified date on

which Haskell was expected to pay for it or return

it. His total liability with C&W when filing

bankruptcy was $1382 ($40.5k) . At the

same time, he had $7,300 ($214k) in receivables, and

about $300 ($8k) in cash. So it was complicated,

and Haskell made it worse. After filing bankruptcy he

collected about $4,000 ($40k) of his receivables and used

the money to pay back the companies who had

commissioned goods with him. A no no. To meet the terms

required for bankruptcy protection, his assets (that

he'd cited as $2,650, an amount that maybe did or

maybe didn't include the $7,300 in receivables), had

to be liquidated, the monies then first used to pay off

the $5,500 ($161k) owed to his secured creditors. Whatever

was left would then be applied to $21,652 in unsecured debt.

Sam continued to record transactions in the same set

of books after filing for bankruptcy. It would

have been easier for him to keep track of the

various interrelationships, and upon investigation

the bankruptcy court registrar, scholarly attorney

Homer N. Hibbard (coincidentally, a fellow Vermont

native), found no hocus pocus in the numbers, but it

made unraveling a bigger task.

IIn the

Last-Straw category: the day after Sam's

bankruptcy filing, a case against him appeared in

the criminal court of justice Peter J. Foote.

One of Haskell's commissioners was a company named

Schaffner & Stringfellow (S&S), a Philadelphia

wholesaler of knitting cotton. One of the garment

makers to which Sam sold S&S's cotton was Sweet, Dempster & Co. (SD&Co) — a Chicago hat maker

who was involved in way too many lawsuits and secretly persuaded

one of Haskell's employees to reveal confidential information. They brought a $1,360 ($40k) criminal suit

against Sam for selling them 2-lb. balls of cotton

knit but delivering 1.75-lb balls. Sam had tried to

compensate S&S for the under-weight parcels,

offering $200 for material already used and a reduced price

on material on their floor, and brought in the attorney he'd consulted who

advised him he'd done all he could.

Nevertheless, the court found against Sam on the

basis that he'd knowingly sold underweight units,

fined him $1,500 ($44k) and charged him with a misdemeanor.

Thereafter Sam's name appeared in the news mostly

relative to political activities.

Simeon Haskell was a business associate of Leroy Payne, father and

grandfather of

Flossie, Barbarabell

and Florence Mueller who were also Iroquois

Theater fire survivors.

5. Sue Siebert,

"Women’s minds were not ‘strong enough’ for

learning," Nashoba Valley Voice, July 11, 2019.

6. William erris,"Old Hutch: The Wheat King," Journal of the

Illinois State Historical Society, Vol. 41, No. 3

(Sep., 1908).

|