|

Nearly six hundred corpses lay in rows at twenty morgues in Chicago on the evening of December 30, 1903.

They were the victims of a fire at the city's newest luxury playhouse, the

Iroquois. It remains today as America's

worst theater disaster. The process of identification

had started at the scene and would last for the

next five days. Relatives streamed through poorly-lit rooms

looking for loved ones amidst bodies of mostly

women and children, blue from trampling, blackened from smoke,

some easily recognized, others charred and

dismembered. Of the searchers, some wore

fine garments and traveled from morgue to morgue

in costly automobiles and hired carriages.

Many more arrived on foot, still wearing singed and soot-covered clothing and

bandages. For them the endless rows of

bodies were a continuation of the nightmare

that'd begun hours earlier at the Iroquois.

They'd escaped the fire but the terrifying scenes in the

theater and grief over lost spouses, children,

parents or siblings would tear at them for years.

For a few, in an era long before recognition of PTSD, it would

lead to suicide and madness.

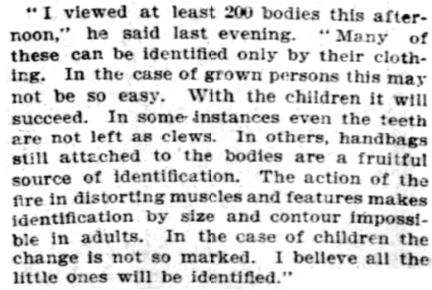

Dr. Joseph Springer, coroner's physician

Chicago Tribune Dec 31, 1904, pg 4▼1

Following a procedure devised by the coroner's

office, police attached a numeric code to each

body and recorded gender and approximate age.

Such possessions as jewelry, purses, pocket

contents and watches were placed in

correspondently numbered envelopes that were

sent to the police department and kept in a

vault. When a victim was identified, the

family was required to produce evidence of their

relationship to the victim before being allowed

to remove the body or take possession of

personal effects.

When a body was badly injured, the contents in its matching envelope

were sometimes critical to verifying an identification.

A shopkeeper's label in a shoe, a receipt in a

pocket, or an engraved watch given as a

Christmas gift five days earlier, all became

part of DVI▼2 in the Iroquois disaster.

Inquest forms were completed for claimed bodies,

and burial permits issued, so that bodies could

be taken home immediately or kept for embalming

and funeral preparation. Identified

victims awaiting transport for burial were

covered with a sheet and searchers were

repeatedly reminded to refrain from removing the

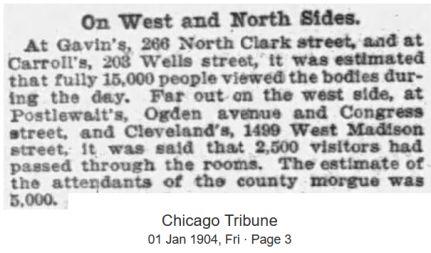

sheets. Thousands streamed through the

morgues, some in search of loved ones, some

indulging curiosity. There were many

victim funerals for the next week but the ground in Chicago was frozen too solid for

immediate interment and after the funerals hundreds of bodies were

stored in crypts until the ground thawed in the

spring.

Hundreds of victims were recognized and taken home that

night in carriages, or transferred to train

stations for shipment. That allowed more space in

morgues for the remaining bodies to be separated

enough for searchers to walk between them and

better see faces and clothing details.

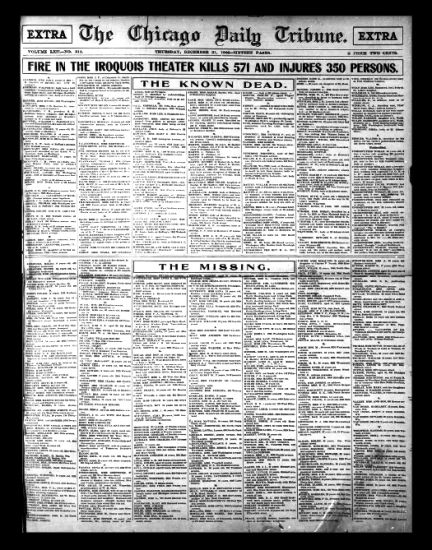

Around midnight police closed the morgues to the

public, to rearrange bodies and compile lists of

the known dead, injured and suspected

missing.

The lists were supplied to Chicago

newspapers and the next day the world learned

about America's worst theater disaster.

For some relatives, the search

went on at home, too, by studying newspaper lists for

clews.▼3 Did Maria have a red velvet skirt?

A blue flannel petticoat? Pearl seed

brooch?

|

|

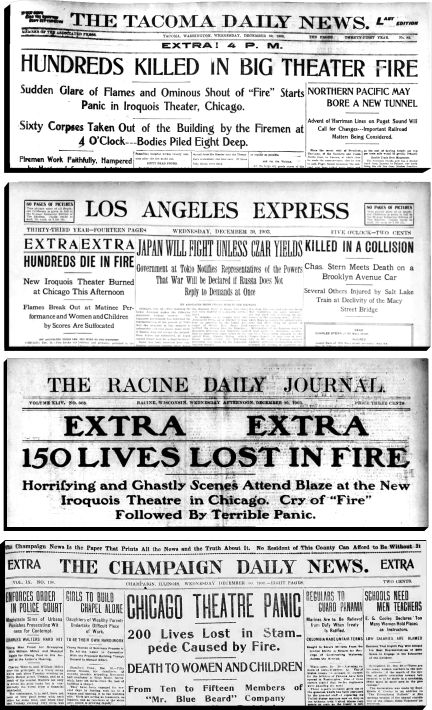

People in some cities learned of the

Iroquois fire that same night, just hours after

the last body was removed from the theater.

In Chicago, while officials shifted bodies and clerks

transmitted victim lists to newspapers, word of the

fire spread throughout the city by

telephone

party lines.▼4 On the west coast, and in

a couple midwest cities, the fire announcement was read beneath gas lights after dinner in

late-edition newspapers. At least

thirty-five cities — two dozen on the west

coast, nine in the Midwest and one in NYC ran

the story on December 30, including seven

special editions.

Though victim names

had not yet been published, messages began to

flow into Chicago's telegraph office. Families in distant

cities sent telegrams after poring over letters from

relatives who had written of

plans to attend Mr. Bluebeard. "Did

Edna go to Mr.. Bluebeard? Wednesday?

A majority of identifications were made within

two days, by January 1, 1904

|

Days after fire |

|

Remaining unidentified |

|

1 |

Fewer than 100 |

|

2 |

224 |

|

3 |

21 |

|

4 |

12 (consolidated at County Morgue) |

|

5 |

6 |

|

|

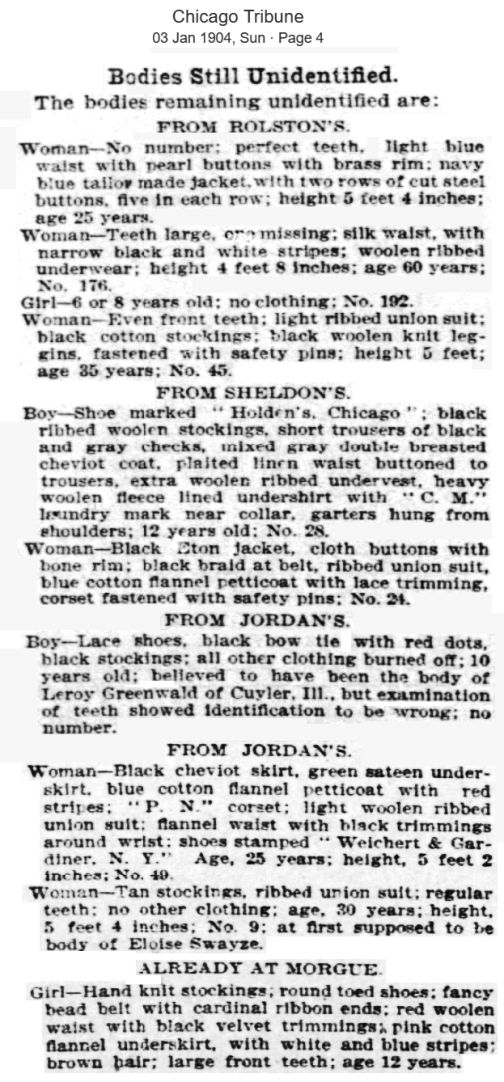

Sobering descriptions of unidentified victims were

published in newspapers

|

|

Discrepancies and addendum

1.

Dr. Joseph E. Springer (1867–1936)

testified at the coroner's inquest by coroner's deputy

Lawrence Buckley. After graduating

from the University of Illinois College of

Physicians and Surgeons he joined the

coroner's office staff in 1898 and remained

until retirement in 1929, becoming a

respected criminologist. One of his

five daughters became a U.S. Marshal.

2. Disaster Victim Identification is

the process of identifying the remains of

people who have died in a mass fatality

incident. Techniques include

fingerprinting, use of dental records and

DNA profiling. In 1903 Chicago, only

dental records were cited, in around

twenty cases. Though finger printing

was being used elsewhere around the world,

including in New York City, Captain Michael

P. Evans of the Chicago Bureau of

Identification had nine months before the

Iroquois disaster pronounced it as

inadequate, based on its use by Pinkerton

Detective Agency, seemingly in a single

instance. Pinkerton had submitted

finger prints in a criminal investigation

but jurors rejected the evidence.

Fingerprinting would have helped in three to

four Iroquois identifications.

3. Clews was an archaic spelling of clue.

4. Long-distance telephone service made it to

Chicago in 1892 but nationally, few of the two million residential household phone

installations had long-distance capacity.

Single-instance long-distance service could

be purchased but cost as much as a week's

pay for the average worker, and depended

upon a recipient answering the phone that

had the willingness and capacity to pursue

an answer that even Chicago residents

couldn't obtain at that early point.

Telegrams were cheaper and faster.

|