|

Michael Bergin

Michael testified at the

coroner's inquest that he saw Iroquois house fireman

William Sallers serving as a doorman at least

twenty-five times. Nothing is known about

Michael. The description of him in newspaper

reports as a "helper" suggest he was young.

Or very old. In Chicago in 1900 was a Michael Bergin, then age

fifteen, oldest son of a widow with four children,

but I found nothing with which to connect him to the

theater industry, in 1903 or later.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: general

Edwin J. Bevis (1866–1949?)

Born as Edwin but as an adult

went most commonly as Ted after 1900. He brought

his ill boss, Slim Seymour, into work the morning of

the fire. He was not listed among casualties

and was presumably on the stage when the fire broke out but

nothing is known of his personal experience.

A native of Ohio, his parents European immigrants,

Edwin and his wife of fourteen years, Anna Erd

Bevis, had one child, daughter Geraldine.

Edwin worked as a stage carpenter in Cincinnati

before coming to Chicago around 1900. After the

Iroquois Theater he went to work at the Grand Opera House in

Chicago and continued in theaters until at least

1910. His career then leapfrogged when he

became associated with cinema pioneer

William Selig. By 1918 Bevis was living in

California, serving as technical director and set

designer for William Parsons and the National Film

Corporation in its production of Tarzan of the

Apes. By the mid 1920s he was a co-owner

of Sympho-Cinema and Eureka Film companies, selling

stock and acquiring acreage for production studios

in Miami, St. Louis, Albuquerque and Cincinnati,

with an eye on Hawaii. The scheme was simple.

They blew into a targeted city and made big promises

about turning it into a film production capital,

producing diagrams of the planned studio and

acreage. Stock investments as small as $75

were then sold to individuals who could not afford

it. It all came crashing down in 1926 when two

of Ted's partners were indicted for using the U.S.

mail for fraudulent stock sale. Bevis wasn't

implicated, in media reports anyway, and there were

no reports of his partners being sentenced, but by

1929 a Florida bank sought Bevis, his wife, daughter

and her husband for non payment of an unspecified

amount. Ted and Anna returned to Ohio by 1930

and are buried in a Cincinnati cemetery.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: carpentry

Orlando H. Butler (1885–1940)

This is an "iffy" identification. Could be the fellow but the evidence is

weak. 1904 newspapers identified this stage

clearer only as "O. H. Butler." No 1900-1905

Chicago city directory listings fit, by name or

employment, suggesting O.H. was not head of his

household in 1903. The 1900 U.S. Census offers

a fifteen-year-old minor, Orlando H. Butler, who was

eighteen in December 1903. Orlando lived one

mile from the Iroquois theater. If this is the

right fellow, he went on to marry Selma Michel,

father three children and become a police sergeant.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: property

Claude

Clayton Calhoun (1880–1936)

Claude appeared on lists of

employees to be called as witnesses

in the coroner's inquest but nothing

was reported as to his testimony.

He eventually landed in Winona,

Minnesota as an electrical

contractor but in the early 1900s

moved between Chicago and Winona,

doing a stint in New York at the

Metropolitian Theater as property

master. At the Iroquois he

probably operated a lamp. In

1908 he married Pearl Campbell and

they had five children. He

died after falling off a curb into

the path of an automobile while

walking home from work.

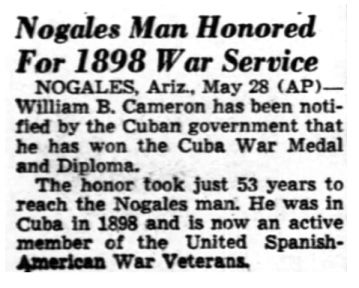

William Benjamin Cameron r (1878–1963)

Twenty-five-year-old William Cameron's name appeared as W. B. Cameron on a list

of prospective witnesses during the coroner's

inquest but nothing was published to verify that he

did testify or, if so, what he said, or even if he

was present on the stage during the fire.

He continued to work as a theater lighting operator

until at least 1911 but by 1918 had changed with the

times and operated a movie house projector. By

1920 he'd left the entertainment world behind to

work as a railroad policeman and in 1930 as a

express bank messenger. In 1910 he married

Alice Lindskog and in 1937 Teresa Moreno.

As a youngster his family had called him Willie.

He was the oldest son of the five children who

survived infancy born to William H. Cameron, born in

Canada, and Kentucky native, Frances "Annie"

Vawter Cameron. William was a veteran of the Spanish-American war, serving

as a private in the Hospital Corps in Cuba.

Over fifty years later Cuba presented an award (see

below). If stationed at the hospital in Siboney, Cuba, William may have met or worked

alongside the legendary nurse, Clara Barton. At the end

of his life William and Maria lived in Nogales,

Arizona. According to his draft card as an

older adult he was of medium height with a stocky

build and brown eyes.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: lighting

John Chism (1877–?)

In 1910 John still worked in

theater lighting, loding in Manhattan with a group

of actors and actresses.

Employer: Mr. Bluebeard Company

Department: lighting

Elizabeth Cleland (1866–1935)

Elizabeth Cleland and her husband were both employed

in theaters. She worked for

Will J. Davis at the

Illinois Theater as the dressing room matron and

assumed that position at the Iroquois. After

the fire she returned to the Illinois and was still

employed in theaters in the 1930s. Her

husband, Thomas J. Cleland, was an electrician at

the Garrick Theater in 1903, having started there in

1897 and still there in 1909. Elizabeth

testified that she had never received instructions

about what to do in the case of fire.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: dressing

Thomas F. Delaney (1876–1946)

Thomas Delaney operated an arc lamp from a bridge

on the opposite side of the proscenium opening to that of William McMullen's

lamp that started the fire. Delaney's

testimony begs the question: did Delaney's lamp have

the same configuration as the one that started the

fire?

Q. Did the proscenium arch border come near your

light?

A. It did when I first went to work, but

I lowered my lamp two feet away from it. It

touched the top of it.

Q. What, in your opinion,

caused the fire, then?

A. The flames from the top carbon — the

soft carbon. [soft-cored rod]

Q. Then the flame could come out through the top of this lamp?

A. Yes, sir; that is the way I surmised.

Not reported was whether there follow up

testimony revealed whether Delaney's lamp fixture

was, like the one that started the fire, a

combination arc lamp and spot light. The

spotlight

McMullen's lamp prevented the top

lamp head from being lowered sufficiently to evade

contact with the curtain. If the two lamps were

not configured similarly, what Delaney did with his

lamp is only relevant insofar as what it reveals

about the offending lamp. (One of many situations in

which I'd like to choke the interrogators and/or

reporters.) Delaney also testified that the

strip lamp on the north side of the stage was

used and in the open position during the scene prior

to the Pale Moonlight performance.

Six months after the fire

Delaney married Minnie Gaffga and they later had one

child. Thomas continued working in the theater

industry until at least the 1930s.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: lighting

Emil Doll

He testified before fire

investigator Fulkerson's inquest the first week of

January, 1904 relative to the wire used to suspend

aerial dancers above the heads of the audience in

the auditorium. Nothing is known of the

details of his testimony or of his biography.

A few months later a boy named Emil Doll was

pleasing billiards fans in NYC and possibly went on

to become a noted golfer but I found nothing to

connect that boy to theaters.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: rigging?

William P. Dunn (1871–?)

As chief electrician for the Mr.

Bluebeard company, Dunn was responsible for

616 incandescent and 25 arc lamps on the stage.

Three years earlier he may have had a different career in

mind, however; in the 1900 U.S. Census Dunn's

occupation was reported as "actor."

It should be noted that he lived in a boarding house on West

36th St. in Manhattan with two dozen other people,

of which seven were actors. The person who

provided information to the census enumerator may

have had an inaccurate understanding of what Dunn

did at the theater. So too another of the

lodgers,

Frank Polin, who was also a member of the Mr. Bluebeard

company stage crew.

William McMullen, employee of the Iroquois

Theater and operator of the lamp that started the

fire, testified that Dunn directed him to operate

that specific lamp, provided by the Mr.

Bluebeard company, from that specific bridge.

McMullen said that though he warned Dunn the curtain

fabric was too close to the arc lamp, he was not

directed to change the lamp position and the curtain

was not removed or contained. It was not

reported when this conversation took place but

McMullen testified that Dunn was a "hard man to talk to."

If McMullen elaborated, it was not reported and the

remark could have many meanings. Was Dunn poor

at listening? An interrupter? Bad

tempered?

Employer: Mr. Bluebeard Company

Department: lighting

Frederick Harry Dutton (1865—1947)

Iroquois Theater lamp operator Frederick H. Dutton lived at 25 N. Irving in 1903.

He and his wife, Francis A. Walton Dutton, were born

in England, Francis arriving in America in the mid

1880s and Fred in 1872. Married in 1886, by 1903

they had two sons, thirteen-year-old Edward and

ten-year-old Earl. A month after the Iroquois

fire Francis gave birth to their third son, Warren,

and in later years they would add Wesley and

Dorothy. Fred worked as a printer as a young

man but went to work in theaters around 1897 and

continued to work on the stage until retirement.

Their 50th wedding anniversary newspaper notice included a

reference to Fred's having helped in the Iroquois

rescue efforts. It is likely he was one of the

men in the chain gang who led chorus girls through

the dense smoke and flaming scenery from the

elevator to the stage door.

(The others included

J. R. O'Malley,

Arthur Hart,

Fred Dutton,

Archie Bernard, Edward Farley

and William Price.)

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: lighting

Richard Emelanz

Reported as badly burned and living

in a boarding house at 288 Indiana St. So far I've

found no one by that name or by Melanz, Milanz, Amelanz, etc.

Though he was cited as an employee of the Iroquois

Theater, with the possibility that he was actually a

member of the Mr. Bluebeard company, I also looked for him in New York.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: unknown

Edward Engle

Engle was among those Mr. Bluebeard company men arrested

the day after the fire, held on $5,000 bond, primarily

to ensure he could be questioned by coroner. It

was reported that Engle was the one who opened the large

double barn doors at the back of the stage. Some

prosecutors and newspaper reporters wanted to make

much of opened stage doors.

Employer: Mr. Bluebeard Company

Department: unknown

Edward Farley (1885–1915)

Called Eddie by his family, eighteen year old Edward Farley was one of six

children born to Delia Costello Farley (1854–1928)

and Terrence J. Farley (1846–1910), of which three

survived in 1903, Edward and two sisters. He left school before

his sixteenth birthday and worked as a messenger boy

before going to work for the Iroquois Theater. His

mother, an 1870 immigrant from Ireland, is described

by one descendant as an independent and feisty

woman who ejected his heavy-drinking

father from the household. I found a

Temperance advocate by the same name, protesting in

a nearby city. Might have been a different

Delia but my guess is it was Edward's mother. Reportedly Delia

was less impressed by Edward helping to save

showgirls from the Iroquois Theater fire (ten

stagehands formed a chain line and when dancers came

off the stage elevator in the heavy smoke, grabbed

them and passed them from one to the other until

they reached the door to safety)▼1 than by his having

left his new coat behind to burn up. (The

others included J. R. O'Malley,

Arthur Hart,

Archie Bernard, Fred Dutton

and William Price.)

In the years after the fire Eddie married a Kentucky girl, Alma M. Talbott

(1997–1972), in May 1915, and gave up his bartending job to go to

work for the Thearle-Pain Fireworks Company.

(Edward was likely one of the new hires for a Therle

plant set up that spring in Roby, Indiana, fourteen

miles from the Chicago Loop. This replaced its

previous facility on Chicago's south side that had

blown up in September, 1914, killing five employees,

including Harry Therle. The firm's patriotic

battle scene themes were especially popular at state fairs in

the Midwest during the first world war and the company was still in

operation in the late 1940s with offices and plants

in multiple major cities.) Eddie and Alma

had been married just four months when his employer sent

him to Detroit to produce a fireworks display for the

66th Michigan State Fair. (Farley family lore pins

his death to Grant Park in Chicago but newspapers

document that his fatal accident took place in Detroit.)

At the fairgrounds, before a grandstand crowd

estimated at twenty thousand, he fired off two

aerial showers and was leaning over to shoot off a

third when it exploded, slamming him to the ground

with crushing strength. He died before

reaching Grace Hospital. His wife remarried

two years later. (Note: Unconfirmed Farley

lore connects

catholic cardinal John Murphy Farley as a cousin

of Edward's father.)

Employer: Mr. Bluebeard Company

Department: property

Walter Golden (1885–1946)

Walter was an electrical

engineering student at Lewis Institute in Chicago (sometimes

credited as the country's first junior college,

merging with Armour Institute of Technology to

evolve into today's Illinois Institute of

Technology). The oldest son of Frank and Mary

(Shulz) Golden, in pursuing a career in engineering

Walter was following in his father's footsteps.

A decade later he married Anna Graceson Knott.

The Goldens were from St. Louis, moving to Chicago

sometime before 1900. For some young men an

experience like the Iroquois fire might drive them

far, far away from theaters but Walter must have

liked it because three decades later he worked as an

electrician in a theater. Could afford live-in

domestic help so had probably advanced beyond lamp

operation. By 1942 he'd gone to work for the

Chicago Board of Underwriters. His WWII draft

card reveals him at age fifty six as 5'7" and

weighing 212. Light brown hair, blue eyes.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: lighting

Edward Grunich (1851–1908)

Fifty-two-year-old Edward

Grunich described his occupation as "machinist."

He and

his wife, Catherine De Beer Grunich, were both

German immigrants. The pair had three grown

children, Emma, Minna and Frederick.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: unknown

James J. Hamilton

At the coroners trial in mid January 1904, James Hamilton,

described as a trunk manager and property boy,

surprised everyone when he described pulling the wire that opened and closed

the vent above the stage about fifteen minutes into the

first act. Prior to his testimony it was

thought, based on testimony from other stagehands,

that the vent remained closed throughout the

performance. Hamilton did not know if someone

else closed the vent after he'd opened it and

nothing was reported as to how far open he'd left

it. Hamilton also gave his opinion that the

fire could have been easily extinguished if there

had been a fire hose on the stage. Perhaps, but

since Hamilton was in the basement break room when

the fire broke out, his opinion on that score was

irrelevant.

Nonetheless, newspapers presented his

opinion as an "aha!" moment.

He offered an alternate

explanation for what some people on the street

thought was an explosion. Witnesses near the theater during the fire

heard and felt a thunderous sound and vibration when fire consumed the

moorings that held up the loft and the multi-ton assemblage of wood, ropes

and canvas crashed to the stage floor.

Hamilton, however, attributed the crash to an big set piece. "Five

minutes after the fire started the big set piece in the shape of a fan, used

as a finale in the second act, fell forty feet to the stage. The piece was

studded with 150 incandescent lamps and weighed several hundred pounds. The

noise of Its fall and the breaking lamps gave forth the sound of an

explosion." Again, however, Hamilton was speaking from theory, not

observation, and the loft weighed many times more than the lighting.

"When I first came up the orchestra was playing and the double octet was singing, with sparks falling all around them. Not a musician nor player moved until it was a matter of life or death.

"The ventilators were

opened, I believe, at every performance. Many times

the draft from them was so strong that it was

uncomfortably cool on the stage." (Then

why, I wonder, would they have been open on a day when it was near zero

degrees outside?)

Hamilton said he stepped onto

the stage and urged the audience to keep quiet.

As did Will McMullen and one other stagehand.

Plus

Eddie Foy. Explaining why so many

audience members testified they saw someone on the

stage saying something.

When his clothes started to

smoke, Hamilton left the building.

Separate next-day newspaper stories credited Hamilton as one of three

different men who led supernumeraries from

the basement dressing rooms out through the coal

chute and up to the street through a manhole cover in the sidewalk. I suspect this was

one of those next-day reporting errors and the

correct name of the man who led performers out a

coal chute was

Robert Murry, the stationary engineer who gave

his account to author

Marshall Everett and was the only one of the three to testify about his

coal chute experience. Hamilton's testimony in

court made no mention of a trip back down to the

basement to save performers. The second improbable coal chute hero was

James

Gallagher.

Hamilton's address was reported as 195 N. Clark but I found no one at that

address in Chicago city directories 1902–1904 by the

name of Hamilton.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: property

Frank C. Harrison (1874–?)

Harrison's testimony at the

coroner's inquest duplicated that of

Thomas Delaney that the

strip lamp on the north side of the stage was

used and in the open position during the scene prior

to the Pale Moonlight performance. Harrison was still

working Chicago theaters in 1920, boarding with

dozens of other theater stage workers and performers

at the National Hotel on East Van Buren.

Harrison was a native of New York; nothing else is

known of him.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: lighting

Arthur Hart

Arthur Hart worked with stage property, moving items on and off the stage as

needed. He testified at the fire attorney

Fulkerson's inquest on January 6, 1904. He was

one of the men who formed a chain line to herd

performers through the thick smoke and flames from

the elevator to the stage exit. (The others included

J. R. O'Malley,

Edward Farley,

Fred Dutton,

Archie Bernard, and William Price.) Arthur

lived at 272 42nd St.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: property

Addison Jasper Hawes (1864–1935)

Addison Hawes saw the fire

curtain descend and stop with the north side eight

feet higher than the south side. The curtain seemed

to him to belly outwards but the smoke was too dense

to see what caused the problem. He saw several

coworkers prodding at the curtain on the north side

with poles in an effort to free it from the

obstruction. Hawes reportedly testified that

he saw no fire hose, hooks, poles or water buckets

or fire alarms on the stage and had never seen

anyone operate the skylight vent above the stage. A

wire hung from the roof to within ten feet of the

stage floor and was reached by a ladder. Addison and

his wife, Josephine Hayes Hawes, were from Wisconsin

and had five or six children.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: unknown

Robert Mathew Hawes (1859–1941)

Brother of another Iroquois stage worker, Addison,

Robert Hawes was married to

Margaret Miller Hawes and had two daughters.

Three years before the fire Robert and his family

were living in Denver where he worked as a gold

miner. By 1910 they would return to Denver

where they remained for the rest of their lives

though Robert may not have lived with his family

1910-1920. Chasing gold, perhaps.

Employer: Mr. Bluebeard Company

Department: scenery shifter

John J. Hickey (1855–?)

Iroquois carpenter John HIckey and his wife, Christina, moved to

Philadelphia, Christina's home state, for a time

after the fire but spent most of their lives in

Chicago. They had two daughters, Mamie and

Elizabeth. John

testified at the coroner's inquest. By 1920 he'd

advanced to stage manager at an unknown theater.

Poor fellow. Just in time for talkies to turn

his world upside down.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: carpentry

H. Hill (Havenhill)

Mr. Hill was interviewed by

the Chicago Tribune. He operated the lamp

designated as #1 on the stage floor, directly below

the bridge on which William McMullen manned the arc

lamp that started the fire. To the Trib Hill

gave his negative opinion of Mr. Bluebeard

stage manager

William Carleton's lax handling of the

strip lights and described the actions of

Carleton's assistant,

William Plunkett.

Employer: Iroquois Theate

Department: lighting

George Hensley

All that is known of George is that he lived at 208

W. Monroe in Chicago. He testified in the earliest

investigation, that of fire department attorney

James Fulkerson.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: unknown

Robert "Dock" Houston

Robert reportedly lived at 1189 Flournoy St. in Chicago and may have been a

carpenter. He testified in fire attorney

Fulkerson's investigation during the first week

after the fire but nothing was reported about his

testimony. Three years earlier an electrician,

T. L. Houston, and his wife, an actress, lived in a

Chicago boarding house.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: unknown

Jacob S. Hovland (1866–1949)

Jacob seems to have worked

part time at the Iroquois while building his real

estate career. He was

called to testify in fire attorney

Fulkerson's investigation during the first week after the fire

but nothing was reported about his testimony.

He lived with his widowed mother, Norway immigrant

Carolina Hjorth Hovland (1830–1913) and one of his

married sisters at 556 Hoyne Ave. His parents

were immigrants from Norway. His father, Ivors,

also a native of Norway, had passed eighteen years

prior. Of the eight children she bore, four of

Carolina's children survived in 1903, of which 6'

tall blue-eyed Jacob was the only son. After

the Iroquois Theater fire Jacob worked as a

wholesale produce merchant but by 1913 had made real

estate his full time job. He married milliner

Della Burgess in 1914 and that same year opened his

Hovland housing subdivision in Evanston, Illinois

north of Chicago. The development featured

low-priced lots without costly building

restrictions. Jacob's business ventures were

prosperous enough that he and Della were able to

travel to Europe and visit relatives in Sweden in

1922, and at the end of his life he was able to

summer in Minnesota's Arrowhead country and retire

to Florida. As a ninety-three year old, by

then widowed, his hobbies were fishing for wall-eyed

pike and raising delphinium, peonies, petunia and

roses. A newspaper notice about his 93rd

birthday party included fun biographical information

about his life, including that he could recall the

Great Chicago fire, but there was no mention that

he'd survived the Iroquois Theater fire.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: unknown

Philip Howard (1862–1949)

Philip was listed as a

prospective witness in the coroner's inquisition but

there were no reports about his testifying so he may

not have been called. He lived with his

mother, Hannah, and one of his brothers at 346 W.

Madison in Chicago in 1903. Hannah bore eight

children. Three years before the Iroquois

Theater fire he had ambitions to become an actor but

seems to have found a niche in stage property

because by 1903 he listed "property man" as his

occupation in city directories and excepting a short

time around 1915 when he stated his occupation as

"stage manager," remained in property for the next

three decades. During most of those years he

lived with his married sister, Josephine. His

obituary mentioned that he was a member of the

Chicago Theatrical Protective Union local No. 2

I.A.T.S.E. No evidence of marriage, children

or his experience at the Iroquois.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: property

Edward Ingram

Edward testified in the first

Iroquois Theater inquest, run by fire attorney

Fulkerson. Nothing was reported about his

testimony, however, and his experience at the fire

is a mystery, as is his residence. Reportedly

Ingram was staying at 126 Dearborn but that was an

office building.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: unknown

James J. Jasper (1866–1918)

James Jasper's name appeared

in a newspaper list as being an Iroquois Theater

employee. Nothing was reported to indicate

whether he testified or was even at the theater the

afternoon of the fire.

James lived with his family at 84 Stave St. in 1903.

He and his wife, the former Emma Stevensen, were

both immigrants from Norway. They married in

1888 and had four children. In 1912 he ran for

county commissioner. The summer of 1918 he

drowned at

Clarendon Beach in Chicago. His oldest

son, Maxwell, became an electrical engineer.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: lighting

Alexander Johnson (1868– ? )

Alexander had worked on theater stages for fourteen years prior to the

Iroquois, including a stint at McVickers. His

testimony at the coroner's trial, including an

erroneous theory about a short circuited lamp,

was latched upon by the Inter Ocean newspaper and

lingers on the web today.

Upon his escape from the

Iroquois he found rigger

John Dougherty lying in the alley with broken

legs from his leap to the alley floor from twenty

feet above. Johnston helped Dougherty reach

shelter.

Iroquois newspaper reports

spelled Alex's name Johnston but he reported the

spelling to U.S. Census enumerator and for city

directories as Johnson. Alexander and his

wife, Carry (thought to have been Christine

Anderson), had immigrated to America in 1883 and

1884, then married in 1889. They lived at 23 Park St.

in 1903 but I failed to find them after that.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: scenery painter

Wilson S. Kerr (1871–1909)

Thirty-two-year-old Wilson Kerr usually assisted with

the fire curtain but wasn't at his post when the

fire broke out. He had taken his ill

supervisor, Fred Seymour, home, in a wagon

or carriage. It was bitterly cold so even a

short wagon ride would have been unpleasant.

According to his later testimony he'd returned to

the theater just before the fire broke out.

The day

after the fire Kerr dropped by the police station to

learn the status of some of his coworkers who had

been arrested. When police lieutenant Patrick D. McWeeney

(1864–1941) asked Kerr what he did when the

fire broke out, Kerr reportedly laughed and said, "I'd

seen something of theater fires before. I made

a run for the fresh air." When he refused to answer

more questions, saying, "I don't know why I should

talk to you," McWeeney locked him up for further

questioning by police chief O'Neill. Kerr was

reported to have told O'Neill, "I had taken slim

Seymour home. He was sick. When I came back to the

theater I had to do his work. I could not do

everything."

According to one newspaper report Kerr was absent

when the fire broke out but another reported he'd

just returned to the theater. Both stories may have

been correct. He may have been absent from his work

station on the bridge but present on the stage.

Kerr was among those arrested and held on $5,000

bond, primarily to ensure he could be questioned by

coroner.

Kerr lived in his mother's

home at 104 Miller St. with she and two of his grown

siblings. His parents were Scottish

immigrants. Wilson D. Kerr Sr., dead in 1881,

had retired from captaining a ship on Lake Michigan

and worked as a custodian at the time of his death.

Mary McDonald Kerr birthed six children.

Wilson jr. had also been living with his mother and

siblings in 1894 when he survived small pox.

Kerr lived for six years after the Iroquois Theater

fire but working as a clerk, not in a theater.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: rigging

Leroy Payne Langford (1885–1945)

Eighteen year old Leroy was working at the Iroquois the day of the fire.

Nothing is known of his experience except that he

escaped. He was the son of Ira W. Langford and

Shiloh Payne Langford, Indiana natives who were

living in Chicago in 1903. In 1910 he was

working as a lamp operator for a theater in St.

Joseph, MO and reported to the US Census enumerator

that he and Clara Hanson had been married for three

years - but they then married again or for real

three years later, by which time he was pursuing a

career as a traveling salesman for Wisconsin Theater

Supply in Milwaukee, WI.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: lighting

John M. Leverton (1862–1929)

In city directories and the

U.S. Census John reported his occupation as teamster

but he was listed in a 1904 newspaper list of

Iroquois Theater employees as a property clearer.

Perhaps he worked part time at the Iroquois as did

another teamster, Charles Sweeney.

Nothing was reported about John's Iroquois fire

experiences, not even whether he was present at the

theater that day. He was a Wisconsin native

married in 1884 to a woman named Euphemia Willett,

and the pair had five children — some born in their

prior location, Abilene, KS, and some in Chicago.

In the odd coincidence department: John died on the

twenty-sixth anniversary of the Iroquois Theater

fire, December 30, 1929, in South Haven, Michigan.

He became a watchman in the years immediately after

the Iroquois fire while still in Chicago then went

to work in a factory after the move to South Haven.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: property

Frank Bedell Lewis (1867–1927)

Frank Lewis was in the

theater business for the long haul, working as a

property man in 1891 and remaining for two decades

after the Iroquois Theater fire. His name was

listed in the newspaper as an employee of the

Iroquois but nothing was reported as to his

experiences during the fire, or even if he was

present that day. He was married to Marie

Antoinette "Nettie" Anderson Lewis.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: carpenter

Arthur Harry Marshall (1880–1862)

Couldn't make this stuff up. In

the 1940s there were two stagehands in Chicago named

Arthur Marshall, both born in Wisconsin in the

1880s, both working their entire lives in the

theater and both working in 1942 at the

Erlanger Theater on Randolph and Clark

(today's Cadillac Palace).

Arthur R. Marshall

(1886–1948), married to Eva, with two daughters. Was a theater

mechanic in the 1930s, nearly 6-ft tall and

slender with brown hair and seriously diabetic

at the end of his life.

Arthur H. Marshall

(1880–1962), was born in Bariboo, married Ella Jeffries, three

years after the fire, had three daughters, and

later married Marie Louise Thibault. Was 5'5"

tall, round and had grey hair. Arthur H.

was a member of Chicago Theatrical Protective

Union local No. 2.

Arthur #2 is probably the one

who was employed at the Iroquois Theater in 1903

because he was older; Arthur R would have been only

seventeen. Nothing was reported about Arthur

Marshall's experience at the Iroquois Theater so

whichever Arthur worked at the Iroquois, he may not

have been working the afternoon of December 30,

1903.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: unknown

Franklin John Massoney (1858–1926)

In 1903 John lived at 977 Milwaukee Ave in Chicago. His testimony was

given at fire attorney Fulkerson's somewhat

unauthorized inquest. Massoney was positioned

on the south side of the stage when the fire

started, the same side as the lamp that ignited the

curtain, but testified that though he saw it seconds

later, he did not see it ignite. Massoney had

worked in various theaters prior to the Iroquois,

and would continue to do so until his death.

He never married.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: carpentry and scene shifting

Maximillian

"Max" Mazzanovich (1870–1950)

Max worked as a stage carpenter for the Mr. Bluebeard company.*

In testimony before the Grand Jury, he blamed the

fire on lamp operator, William McMullen. According

to Max, McMullen must have done something improper

or the curtain would not have caught fire. State

prosecutor Albert C. Barnes was dismissive of

Mazzanovich's analysis of the fire's start because Mazzanovich was outside smoking at the time and did

not see the fire until it was well underway.

Max was among those arrested and held on $5,000

bond, primarily to ensure he could be questioned by

coroner. He was represented at

arraignment by

Thomas S. Hogan.

Max's joined the group who

struggled to un-snag the fire curtain from the

proscenium

light strip. His testimony at fire

attorney Fulkerson's inquest on Jan 1, 1904 revealed

newly published information. He said when he

and others began wrestling with the fire curtain the

fire was at the "arch curtain," just four curtains

behind the fire curtain.

Max had a bad history with

arc lamps. On April 17, 1886 was injured in an arc

lamp explosion on the stage of "The Three Guardsmen"in Janesville, Wisconsin where the Alexander Salvini

company was performing at the Meyers Opera house and

Max had a small role.

It appears that Mazzanovich

may have first tried to make it as an actor and

turned to stage carpentry later. In addition

to the Three Guardsman, his name turns up in

1902 as a performer in Hearts Aflame.

It closed after eight performances. According

to his obituary he went to work for George M Cohan

soon after the Iroquois Theater fire and over the

next thirty-five years designed the scenery for most

of Cohan's productions. Perhaps but I found

him credited with just two: Friendship in

1931, closing after one month, and in 1923 the

Rise of Rosie O'Reilly, running for three

months.

An Oakland, California

native, he was the son of an Austrian immigrant,

Lorenzo Mazzanovich, his mother thought to have been

named Margaret, and was himself married to a woman

named Orme, with whom he had a daughter named

Maxine. Artistic expression seems to have been

a family trait. His brother, Lawrence

Mazzanovich, who happened to live in Chicago at the

time of the Iroquois Theater fire, was a landscape

artist of some note and another brother, Anton

authored a book about his adventures in the wild

west, Trailing Geronimo. One newspaper

reference to Max relative to the Iroquois Theater

identified him not as Max but as John C. Mazzanovich,

a theatrical scene painter, leading me to wonder if

Maximillian was a stage name or if there was a

second man named Mazzanovich in the Iroquois stage

crew. I suspect Max had a brother named John

but he died in 1886. Sometimes his last name

was miss spelled Mazzonovich (mazzo rather than

mazza) and sometimes Mazzanowich (wich rather than

vich).

Employer: Mr. Bluebeard Company

Department: carpentry

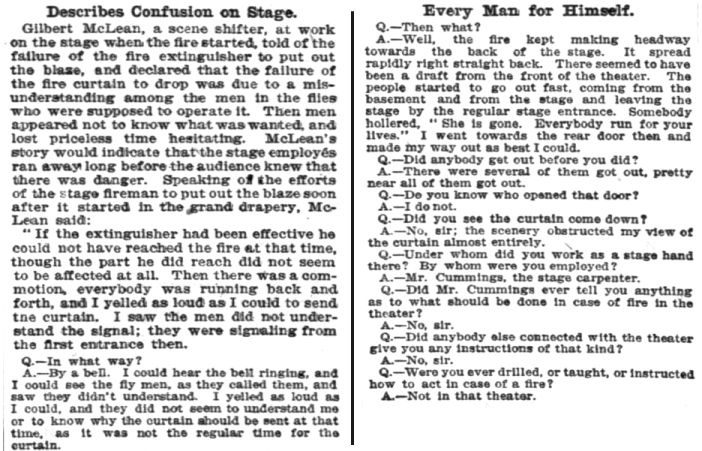

Gilbert or Willard McLean

McLean testified at the

coroner's inquest in early January, 1904. (See

accompanying clipping). Since his view of the

fire curtain was obstructed by scenery, his opinion

about it's operation during the fire was of limited

usefulness. His description of fireman

Sallers' attempt to extinguish the blaze with

Kilfyre tubes corroborated that of other witnesses.

At point of origin the blaze was almost beyond the

reach of the tube chemicals and the edge of the

flames that were reached did not appear to be

diminished by the dry chemicals. Gilbert had

gone to work at the Iroquois Theater when it was

first opened, five weeks before the fire. One

Chicago newspaper reported his first name as

Gilbert, Another as Williard. I failed to find

a man by either name that was definitely the

stagehand at the Iroquois.

Employer: Probably Iroquois Theater

Department: scene shifting

John S. McCloskey (1866–1940)

When the fire broke out,

thirty-seven-year-old McCloskey (sometimes miss spelled as McCluskey) ran

to the nearest fire house, Engine House 13 on

Dearborn, to report the fire, then

ran back and helped women jump off fire escapes in

Couch Place alley. Brooklyn-born McCloskey had

worked at theaters around the country for twenty

years and as assistant stage carpenter at the

Iroquois since it opened. He wired the fire

curtain at the Iroquois with four 3/8"-thick wires, joined at the

north end of the stage to a 2" manila rope. He

testified that the curtain was lowered before every

performance and that it always worked properly.

One newspaper reported that McCloskey denied the

presence of strip lights while another reported his

more likely testimony, in keeping with other stage

workers, that he did not know what caused the

curtain to hang up and belly on its descent, that it

might have been the strip lights. That same

newspaper reported his observation that the Iroquois

was below average in its fire protection equipment.

John was married to Ida Morrell McCloskey and lived

at 154 S. Wood.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: carpentry

Thomas H. McQueen

McQueen was among the Mr.

Bluebeard company from New York who was arrested and held on $5,000 bond,

primarily to ensure he could be questioned by coroner.

He was represented at arraignment by

Thomas S. Hogan. He testified at the coroner's

inquest in mid January, 1904, during which it was

reported that he'd broken two ribs escaping from

theater but the report did not describe how that

happened. Probably jumping into Couch Place

alley.

Employer: Mr. Bluebeard Company

Department: mechanic

Frank Miller

Frank's name appeared on a newspaper list of Iroquois Theater stagehands with

nothing to indicate whether he was at the theater

the day of the fire. Many dozens of men named

Frank Miller in 1903 Chicago, many in possible

occupations (electrician, carpentry, painter,

general labor, etc.). No serious expectation

of learning more about Frank the stagehand.

Safe to say that he didn't testify at any of the

various inquests and trials.

>

Employer: probably Iroquois

Theater

Department: unknown

Jacob "Jake" Motz (1865–1916)

Jake Motz immigrated to America

with his parents from Germany as an infant. His

first wife, Kate, passed around 1900, leaving him with

three children, age ten, seven and three. He married Lillian

that same year, a second

marriage for both.

He testified in fire

attorney's inquest and at the coroner's trial that

there were only Kilfyre tubes on the stage and that

there had been no instructions about how to respond

in the event of fire.

By 1910 he and Lillian moved out of Chicago altogether,

back to St. Louis, where he'd lived with his first

wife. He continued working in the theater for

the rest of his life.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

br>

Department: rigging

Frederick Fred Nolan (alias Fred Pigeon) (1869– ?)

(See passport photo in montage at

top of page)

1903–4 newspapers reported

that Pigeon was Fred's real name and Nolan his alias

but I think it was the opposite. He was born

Fred Nolan to William and Rose Nolan. He was

among the Mr. Bluebeard stagehands arrested

and held on $5,000 bond, primarily to prevent them

from leaving Chicago, to ensure they could be

questioned by the coroner. Nothing was

reported about Fred's testimony. He was

represented at his arraignment by

Thomas S. Hogan.

Am pretty sure he was a vaudeville / burlesque

comedian specializing in Irish characters who worked as a stagehand between

performance gigs. It appears he picked

up with Mr. Bluebeard road company in

Pittsburgh when his performances at the Southern

Amusement Park came to an end. Bluebeard

opened in Pittsburg on 9/21/1903 and Nolan's last

performance at Southern was on 9/30/1903. He

seems to have continued working as a stagehand until

November 23, 1905 when he returned to the footlights

and mostly remained there until 1924, abandoning the

Pigeon alias altogether, when he retired from

performing and went to work as a property

man for Sliding Billy Watson's show until at least

August, 1924. In January, 1919 he went to France

with America's Over There Theatre League. No

evidence of a marriage or children, probably died

1924–1930. When not on the road he lived with

his widowed mother until her death, then with a

sibling and his family, always in Bayonne, NJ.

An overview of his schedule is below.▼5

Employer: Mr. Bluebeard Company

Department: carpentry

Peter O'Day (1849/57 —1927)

Peter testified at the

coroner's inquest the morning of January 12, 1904

and again a month later at the grand jury trial, at

which a portion of his testimony was reported:

"My duty was to

pull out these proscenium lights after the

curtain went up on every act. When they were out

the curtain could not drop, and so I had to push

them back again before the close of the act. I

had pulled the light at the north end of the

stage, and when the fire started I was at

another point of the stage. I could not get to

the light to push it back again, so it caught

the curtain."

He also testified about panic

on the stage, the opening of the stage doors and

that the asbestos curtain was fastened to wood

battens but that portion of his testimony was not

reported. In 1903 newspapers his name was

spelled sometimes as O'Day and sometimes as O'Dea.

Both a Peter O'Dea and a Peter "O'Day were listed in

the 1903 Chicago city directory but the Peter who

worked at the Iroquois lived on Mather St.,

residence of O'Day, and in the 1900 and 1910 U.S.

Census it was O'Day who had a career in the theater.

When the second grand jury

met, O'Day was one of many witnesses the prosecution

could not locate. The family was still in

Chicago, had just moved.

Prior to working at the

Iroquois Peter worked as a carpenter and a bill

poster.

(This fun 1920 book describes the trade of bill

posters and advance men.) Seven years after the fire he

described his occupation to the census enumerator as

"actor." He had immigrated to America from

England in 1864 with his parents as a child, grew up

in Flint, Michigan, married Bridget Kerne in 1889 and by 1910

had seven children, age three to twenty-four, only

one son in the lot. A Peter O'Day of the right

age set out in 1920 for a 300-mile ride through

Michigan on an Evans powercycle.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: lighting

C. O'Dell

Breadcrumb note for later

reference. This individual, presumably male,

was listed as an employee but not as a testifying

witness thus it isn't known whether he was even at

the Iroquois the day of the fire. While he

probably lived in Chicago, it's also possible he was

in the Bluebeard crew and a NYC resident.

Looked for males named Odell or O'Dell with related

occupations in Chicago and Manhattan/Brooklyn in the

1900 and 1910 US Census, and in 1903 & 1904 city

directories. In Chicago was a William O'Dell who was

a "tabulator" in a theater in 1900 and a circus

performer in 1910, and a Charles Odell who worked as

a painter (not necessarily in a theater) in 1903.

In 1910 there was a Charles W. Odell, age

twenty-seven, who worked as an electrician for the

telephone company but seven years earlier could have

been an intern manning a stage light.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: lighting

Arthur O'Leary ( 1876– 1904)

Arthur's name did not appear in newspaper lists of Iroquois Theater employees.

A year after the fire, a notice appeared in the

January 8, 1905 Decatur, Illinois newspaper of his

death a week earlier. The nine lines of text

reported that he had been operating the

calcium lamp during the Iroquois Theater fire and

died as a result of smoke inhalation while trying to

save others. He was not operating the lamp

that started the fire but his family and/or the

Decatur newspaper may not have known better.

Further investigation turns up that he died in

Chicago on December 14, 1904, age twenty-seven. A

Michigan native, he was one of sixteen children born

to Irish immigrants, John D. O'Leary and Ellen Hart

O'Leary. His mother averaged a pregnancy every

17.5 months for over twenty years with a two-fer on

the twins, Romeo and Juliet. John

supported his brood on the wages of a railway

passenger agent selling luxury pkgs.

Prior to going to work at the

Iroquois Arthur worked as a clerk in a dry goods

store. I've failed to find any other published

reference to his employment at the Iroquois, or any

other theater. Curiously, nor did Chicago

newspapers reference the Iroquois fire in his

obituary, though they jumped on other stories

involving delayed Iroquois deaths. I failed to

find a connection between his family and Decatur, IL

that might explain why that newspaper ran a story

connecting O'Leary to the fire. All

considered, it seems fair to assume his name was not

added to the victim list. To medical

practitioners of 1904 the symptoms of influenza, consumption and inhalation injury

might have been similar. Without more information about his

condition between the fire and his death, about all

that can be said is that any damage caused by the

fire may have been exacerbated by influenza or

consumption.

Julia Berger was another such case.

Arthur's funeral was held at St. Mary's church and

he was buried in Mount Olivet cemetery on Friday,

December 16, 1904. Assuming there was a family

resemblance between he and his brothers, Arthur was

tall with a medium build, brown hair and grey eyes.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: lighting

J. R. O'Malley

O'malley was among the stagehands who formed a chain line to direct chorus

girls emerging from the elevator through the smoke

filled stage and out the door. (The others

included Arthur Hart,

Edward Farley,

Fred Dutton,

Archie Bernard and William Price.)

Nothing was reported as to his address. I

looked at every John, Jacob, Joseph, James, etc. in

1900–1910 Chicago and found none with an occupation

I could tie to the theater with any certainty.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: scenery

John William Pickles (1857–1913)

At an inquest conducted by fire department Fulkerson a week after the fire,

Pickles testified that there had been an explosion

and fire in the basement at the Iroquois on opening

night, November 23, 1903, five weeks before the

disaster. He heard "a loud report" and saw

flames come over the top of the 8-ft high partition where was

located but it was put out quickly and by the time

he went to investigate, a crowd gathered at the

doorway into the area where it occurred prevented

him from seeing into the area. He was told it

involved a gas tank. His name was misspelled

in that newspaper story as Bickles and in an

out-of-state newspaper his name was given as John

Nickles and identified as a construction contractor

working at the Iroquois.

John and his wife, the former

Amy Lunt, and their six children, lived at

6711 Rhodes. A seventh child

was born four months after the Iroquois Theater

fire, named after her mother, but the little girl

died two years later. John and Amy had married

in England in 1883 and came to America a couple

years later. All but their oldest child was

born in the United States. John worked as a

stage carpenter until the end of his life.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: carpentry

William Price

William was one of the men who formed a twenty-foot chain line to herd

performers from the elevator car to the exit as they

came down to the stage floor from the dressing rooms

above. (Others in that group:

J. R. O'Malley,

Archie Bernard, Arthur Hart,

Edward Farley and

Fred Dutton.) There were

thirty-three heads of households named William Price

in Chicago in 1903, including a superintendent of a

sheep house, but none with an occupation that can be

definitely tied to the stage. The Everette

Marshall disaster book reported that William's

clothing was on fire by the time he left the

building.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: possibly property

John Schmidt (1877–1932 maybe)

Reported as being

John Dougherty's rigging assistant, at least for

the afternoon of December 30, 1903 while Slim

Seymour was out sick, twenty-six-year-old John

Schmidt wasn't scared away from the theater by the

Iroquois fire and his subsequent arrest. He

remained in the business for at least the next

twenty-seven years.

He was arrested for manslaughter and held on $5,000

bond. In advance of his testimony newspapers

reported that prosecutors hoped he would be able to

shed light on the

strip lights and the failure to lower the fire

curtain. There were no follow up reports after

his testimony but it likely mimicked testimony from

others because the coroner's jury didn't see fit to

hold him over to the grand jury.

In 1903 John lived at 75 Sangamon in Chicago, having

moved out of his widowed mother's home. She is

thought to have been Christina Schmidt. (There

were over fifty John Schmidt's in Chicago and I

don't feel certain that the John Schmidt who was at

the Iroquois is the same John Schmidt who worked in

Chicago as a stagehand from 1920–1930, married in

1911 to Eva Lively, or that the same John Schmidt

who was the son of German immigrants Ernst and

Christina Schmidt. Hoping to some day hear

from a descendent of one of his siblings.) He

was tall, slender and had dark brown hair.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: rigging

Fred "Slim" Seymour

Slim Seymour was head of the riggers at the Iroquois Theater, and 180

scenery and curtain drops.

Suffering from pneumonia▼2 Seymour was brought to

work by one of his crew members, Ted Bevis, but

taken back home shortly before the fire started by

rigger Wilson S. Kerr, a rather

bad-tempered fellow.

John Dougherty stepped in to substitute, reportedly described by

Seymour as the most experienced man in the crew.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: rigging

Edward Sherman (1880–1977)

Edward's story

Employer: Mr. Bluebeard Company

Department: properties

Frederick Shott (c.1875–1911)

Commonly spelled Schott and sometimes misspelled as

Shotts and Schotz, but in city directories and the

US Census enumerator Fred went by Shott.

At the coroner's inquest in

mid January 1904 Shott testified that he ran to join

four other stagehands try to lower the fire curtain

by removing the hitch pin from the

strip lamp

hinge. When the lamp

still could not be closed (possibly because the

weight of the curtain pressing down from the top was

causing misalignment of the leaf curls in the hinge

knuckle, or failure of the hardware brackets), he

escaped via a fire escape door.

Twenty-eight-year-old Frederick Shott reported his

occupation as "candy maker," a full time job in 1900

and still his occupation a decade later. The

stage was a part time job, possibly only on December

30, 1903.

Four years after the Iroquois Theater fire Fred

married a German Hungarian native, Elizabeth Susie

Anderjak, and the pair had two sons. The

second boy, Fred's namesake, was born six months

after Fred's early death in his mid thirties.

Susie became a janitress and raised her boys alone.

Didn't find notice of her death. Hope she

remarried.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: rigging

Frank Sickinger

Frank Sickinger testified at the coroner's inquest in mid January 1904 that he

had joined the men trying to lower the fire curtain

that caught up on a

strip lamp. He did not know if the fire

curtain was made of asbestos and was unaware of any

effort to open the roof vent over the stage.

Frank lived at 210 E. Ohio St. in Chicago.

Nothing more is known about him.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: department unknown

Henry Siegel

At fire inspector Fulkerson's inquest Henry testified that he operated a portion

of the wires used to suspend the aerial dancers in

the air above the auditorium. He reported that the

wire that would have been attached to Nellie Reed

did not and could not have interfered with operation

of the fire curtain. "When the wire was not in use

its lower end was fastened to an upright wire

running up the proscenium arch, six inches or more

outside the curtain when lowered. When the act was

to be performed the wire was loosened and fastened

to the harness of the young woman. The curtain could

have been lowered without touching the wire, whether

in use or not."

Note: In a separate news

story mention was made to a Mr. Bluebeard cast

member named Henry Seeger. The similarity of

the names causes me to wonder if it is the same man.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: Rigging

Charles F. "Smithy" Smith

Smithy was operating a lamp

on a bridge on the south side of the stage when the

fire broke out, with Charles Sweeny. They

grabbed tarps and tried to smother the fire but it

was quickly beyond their reach. Nothing more

is known about Charles. A man named Charles

Smith appeared on Iroquois victim lists but nothing

was reported indicating that Charles Smith the

stagehand was injured.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: department lighting

Robert Smith

Known only as Robert Smith,

his age, address and relatives never reported, the

elevator operator on the Iroquois stage made three

or a dozen trips to six floors of dressing rooms on

the south wall of the stage to bring down cars full

of performers. (Some reports said three, others a

dozen.) Some accounts said they had no other egress

but one stagehand testified about some performers

escaping from the dressing rooms via a catwalk

leading to a spiral stairwell on the opposite side

of the stage. Upon reaching the stage floor they

were grabbed by a twenty-foot long chain line of

stagehands (including J. R.

O'Malley,

Archie Bernard, Arthur Hart,

Edward Farley,

Fred Dutton and William Price)

and passed from one to another until they were

safely outside the theater. Nearly overcome by

smoke, his hands burned, on his last trip Smith ran

through the dressing rooms and dragged a few

stragglers to elevator car that by then had caught

fire. It was reported that he was permanently

crippled from injuries to his hands.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: elevator operation

Charles L. Sturgis

Sturgis lived at 318 State

St., site of Silver Moon Restaurant, owned by H.

Chasky. Building was previously a saloon and

an anatomy museum. Charles testified at the

Fulkerson inquest the first week in January.

There was an actor named Charles Sturgis in Chicago

in 1890s, presumably not the same man.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: unknown

Charles P. Sweeney (1881–1943)

One of the flymen hired by

Seymour, twenty-two-year-old Charles Sweeney (spelled Sweenie

in newspaper reports, Sweney in city directory and

Sweeney in official records) was a teamster (as in a

driver of a horse-drawn wagon) who had

worked part time at the Iroquois since its opening. He was

seated on a bench about ten feet from the proscenium

opening on the lowest level bridge on the south side of the

stage, above and a bit to the west of where the

fire started. With him was lamp operator

Charles T. Smith and one or two other stage workers.

The others were there keeping warm while waiting for

their next duty call. The north side of the

stage where a majority of the flymen were stationed,

was colder than the south.

Sweeney's job was to use a

fouling pole to keep drops from becoming entangled

during ascent and descent. In court testimony

he described noticing a flame, running to look over

the pin railing see what it was and calling out

across the stage to John Dougherty to lower the fire

curtain. He and Smith then tried to smother

the fire with tarps (seems like that might have just

fanned the flames). Recognizing that the fire

had grown out of control, Sweeney ran up steps to

the sixth floor dressing rooms to alert

performers.▼3 He led an unknown number of

female performers down the stairs to the stage floor

and escaped with them out the Dearborn street

audience exit.▼4

Charles was one of two

children born to the late Frank Sweeney of Canada

and Jennie Beard/Baird Sweeney of Scotland. In

1903 his father had been gone for seventeen years,

Charles had been married for one year to Beatrice

Johnson, and his mother lived with them. By

1910 he was the father of two daughters and

presumably left his teamster and theater jobs behind

when he found work as a shipping clerk for

the National Meter Company, manufacturer of water

meters and gas engines. In 1913 came a third

daughter and his mother's marriage to James Mott.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: rigging

Cal Wagner

Bread crumb note for later

research.

Cal's name appeared on a list supplied to

authorities of everyone who worked at the Iroquois

but it wasn't clarified whether all on the list were

on duty the day of the fire. I chewed up time

chasing the idea that this was Happy Cal Wagner

(1840–1916), legendary blackface performer and

producer. Happy Cal and Davis had ample

opportunity to be acquainted through their mutual

association with Jack Haverly but it looks as if

Wagner was in Syracuse, NY in 1903, on December 30

probably grieving the death of his wife three weeks

earlier. There wasn't a Cal or Calvin Wagner/Wagganer/Waggener

in Chicago in 1902–1904 according to Chicago city

directories but those only listed heads of household

so I checked 1900 and 1910 U.S. Census and he wasn't

listed there either. So I looked for a man by

that name anywhere in the country from 1900-1930 and

found nothing. Then everyone named Cal or

Calvin with an occupation designated as in a

theater. Nothing but learned there were a

surprising number of Stage Road's in the country.

Employer: Mr.

Bluebeard Company ??

Department: unknown

John Whitten

Other than his address the first week in 1904, 363 Van Buren, and

that he testified in fire attorney Fulkerson's inquest,

nothing is known about Whitten.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: rigging

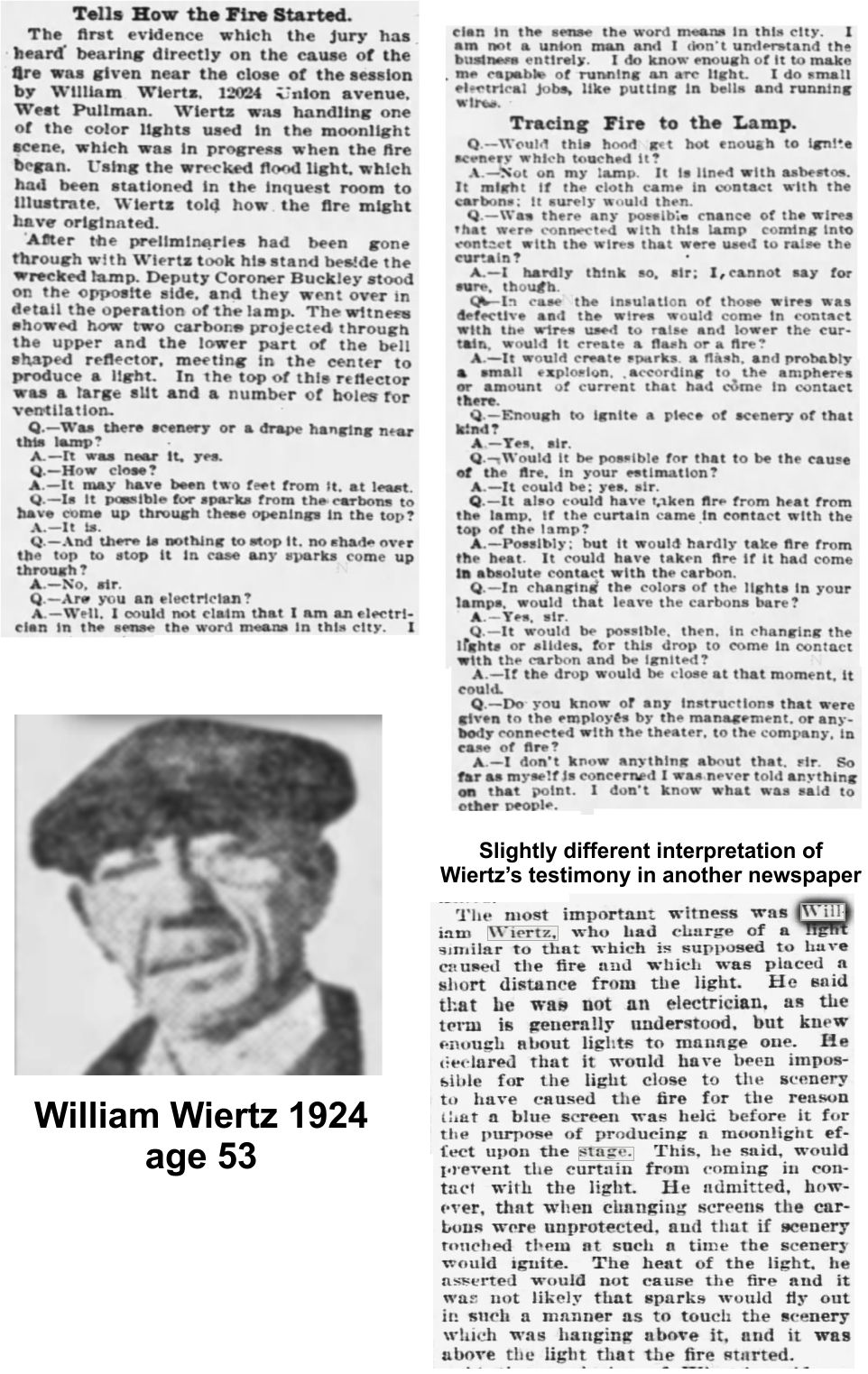

William Henry Wiertz (1871–1958)

Thirty-two-year-old William Wiertz lived on

Union Avenue in West Pullman. He was a versatile

man. In addition to working

at the Iroquois operating arc lamps and doing small

wiring jobs, he worked as a bicycle repairman and

before that sold coffee. His

testimony at the coroner's inquest shed light on how

sparks or direct contact with the carbon rods, could

have ignited fabric.

A native of Holland, he and his wife of six

years, a Swedish girl named Ericka Engelholm, had

two young children. Three decades later their

family had grown to six children and he was still

working in Chicago theaters but Ericka had passed

and he'd remarried.

One son, Vernon, born in 1903, the year of the

Iroquois fire, only attended school until the second

grade and spent his life in institutions.

In 1949 at the Iroquois Theater memorial

association's 46th anniversary program, William told

a story that was not reported in 1903, leastwise his

role was not reported, about his attempt to rescue

aerial ballet dancer Nellie Reed. This is

one of at least three conflicting stories about

Nellie's last moments at the Iroquois.

Employer: Iroquois Theater

Department: lighting and carpentry

|