|

In

1903, Chicago was home to America's worst theater

disaster, a record held still. The short

version of the story is that at the city's newly constructed

Iroquois Theater, a stage fire spread to the

auditorium and killed nearly six hundred people.

The longer version consumes this

website. This page is about one of

the scavengers who tried to capitalize on

tragedy.

There were street

thieves who stole belongings from

corpses, and a professional con who

stole a corpse. More common were advertisements for life

insurance companies and manufacturers of

products promised to simplify

firefighting or prevent gaseous fumes

during future such fires. National

Fire-Proof Paint went so far as to claim

the Iroquois disaster wouldn't have

happened had their paint been used at

the Iroquois. A few

life-insurance companies published the names

of their customers who had died in the fire — along

with the amount of their policy, and name of the beneficiary!

The subject of this page used the Iroquois disaster

to give his career a boost.

Twenty-five-year-old William Clendenin (1878–

1952) was a self-proclaimed fire expert who lived in Chicago.

He earned a living writing about fires in

commercial and municipal structures for

a Chicago-based publication named Fireproof Magazine. For

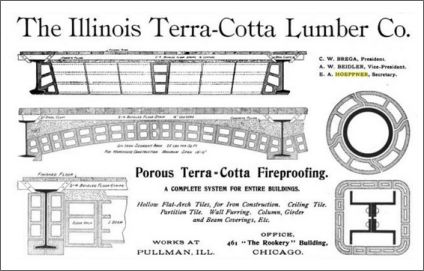

his employer, a trust of terra-cotta tile

producers, the magazine provided a way to pound

on its promotional message: concrete/cement

construction and sprinklers were very, very bad;

terra-cotta tile construction was perfect.

The #1 goal of Fireproof

magazine was to promote terra cotta tile

sales. The #1 goal of William

Clendenin was to build his brand.

Clendenin submitted his stories from the

magazine about large structural fires to newspapers

that were happy to receive free content

that drew eyeballs. Newspapers

didn't know enough about the fire to

recognize his deceptions and reject the story.

So avid was public interest in the Iroquois

Theater fire that newspapers published everything they could get

their hands on (including stories about people

who lived hundreds of miles from Chicago and

merely thought about going to the Iroquois

Theater, if they happened to be

in Chicago). Newspapers jumped on

Clendenin's Iroquois story. As do

bloggers and book authors over a

century later unaware of its

inaccuracies and falsehoods.

Clendenin ignored courtroom testimony

from hundreds of witnesses.

Most egregious was Clendenin's absurd claim that plaster rained

down in the Iroquois Theater auditorium, killing

people directly by falling atop

them and killing others indirectly by

increasing panic amongst people on the first

floor who thought the balconies were falling.

In ten years of studying weeks of published interviews and

testimony from survivors and first

responders, in dozens of newspapers in

six states, I've found zero talk about falling

plaster or fear of falling balconies.

Busy newspaper editors cannot have been

expected to recognize that the only one talking about

falling balconies was William Clendenin:

|

"The arch, or ceiling, was covered with

a cheap concrete. The first puff of flame

destroyed this. It crumbled

away, exposing the twisted mass of steel

reinforcement and girders, and fell on the

audience.

This killed many.

Looking from below, the

bewildered, choking and

maddened crowd thought

it was the result of a

panic above. They

believed the galleries

were falling and, in the

rush resulting, many

more were killed."

|

In addition to the absence of witness testimony,

evidence that Clendenin's attempt to blame deaths on concrete

is malarkey is found in the fact that only a handful of people sitting

on the first floor were killed, and they died

from falling bodies from the balconies, not falling concrete.

Check out the photo below taken the day after

the fire and you'll see two small patches of

plaster on the floor, each about 18" x 24" in

diameter. As Clendenin well knew,

fear of falling

balconies killed no one. His

deception was intentional.

|

|

|

In addition to falling plaster, Clendenin's alternate facts included:

Condemnation over the Iroquois being equipped with a poor quality fire curtain

Top-of-the-line or trash, the quality and construction of

the Iroquois fire curtain was as irrelevant

as what Eddie Foy ate for breakfast.

On its way down, the curtain hung up on an

obstacle,

a light fixture on the north side

of the proscenium arch, creating a gap between

the curtain wall and the stage floor that was large

enough to ride through on an elephant. A

backdraft into the superheated gaseous area of

the unventilated stage combusted and expelled a giant fireball

through that gap in the curtain into the

auditorium where it was drawn up to the

northeast corner of the structure by a

ventilation shaft fan and opened fire exits, killing the

roughly four hundred people

in the balconies who had not yet escaped. Given

the built-up heat on the unventilated stage, the

backdraft, and the gap below the fire curtain,

the death count would have been the same if the curtain had been made of

ten-inch-thick stainless steel.

Over a century of discussion about the quality

and construction of the Iroquois Theater fire

curtain has been pointless.

Corrupt Chicago politicians and city officials

Clendenin all but called Chicago mayor

Harrison playground names, but gave no

specifics or examples. The prior

year he had condemned Harrison's appointed

Building Commissioner, Peter Kiolbassa,

going so far as to blame the deaths of

fourteen people on Harrison and Kiolbassa—with a

similar lack of substantiation. During

a graft inquest a few weeks prior to the

Iroquois Theater fire, investigators reported

that of hundreds of tips received, a majority

were unverifiable. Clendenin's corruption

accusations were equally specious.

Concrete is the Devil's work

For Fireproof Magazine, every fire presented an opportunity

to condemn concrete and promote tile.

On a good day, they wedged in anti-sprinkler

stories, too. Cledenin made much about

wire lathe and cement used on the corners of the

proscenium arch at the Iroquois Theater and,

like the fire curtain, though irrelevant,

implied that it played a role in the fire.

|

The titular head of Fireproof Publishing Company was E. A.

Hoeppner, an officer in Terra-Cotta

Lumber Co. of Pullman, Illinois. Terra-Cotta Lumber

was owned by National Fire Proofing. From

1999 to 1902, NATCO had acquired twenty-nine

manufacturers of architectural terra cotta. This gave them control

of 65% of the industry.

Wonder if other

advertisers knew they were putting money

into a competitor's pocket. Probably.

Terra-cotta trusts got started around 1890

and Terra-Cotta Lumber was founded ten years

later. The first trust-busting investigations

came to their industry in 1909 and lasted a

decade. By 1920, price fixing had

become so much the norm that they didn't try very hard to conceal

it, like they knew their days were numbered.

Indictments, fines and prison

sentences for Sherman Act violations

came in 1922. The cement and concrete

trusts were broken up too, probably pleasing the

terra-cotta crowd no end.

|

|

|

Party's over

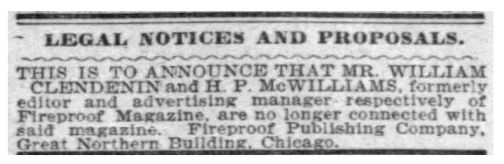

Clendenin appears to have run afoul with his employer

about a year after the Iroquois Theater fire. The publisher

disassociated itself from him beginning in August 1904. Legal

notices began appearing in newspapers for a

month.

After writing for Fireproof, Clendenin went to work as an

advertising copywriter, first for an agency in

St. Louis then at several different Chicago agencies.

By 1930 he was working as a bookkeeper and by 1940 had disappeared,

presumably deceased. Fireproof

magazine was around until at least 1911.

|

People in Chicago's building trades knew Clandenin was a bad

actor. Architects and engineers challenged his assertions

in op-ed pieces but he continued until relieved of the

Fireproof assignment.

|

|

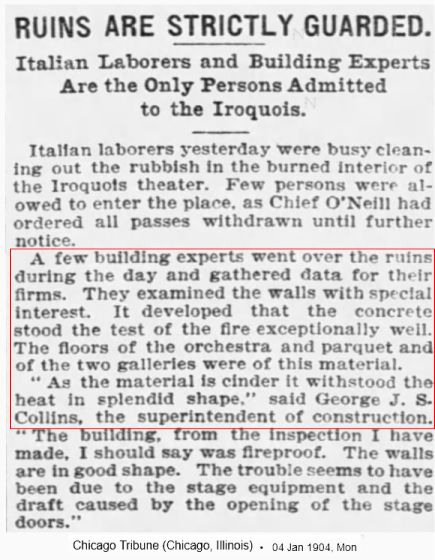

George J. Schilling Collins (1863–1927) was an

insurance agent turned construction engineer. He was born in London and

spent his boyhood in south Africa. His remarks might have been a

non-confrontational rebuttal of Clendenin's harangue two days earlier.

|

|